Chapter: Medical Microbiology: An Introduction to Infectious Diseases: Mumps Virus, Measles, Rubella, and Other Childhood Exanthems

Rubella Infection

RUBELLA INFECTION

Infections by rubella virus are often mild, or even asymptomatic. The major con-cerns are the profound effects on developing fetuses, resulting in multiple congen-ital malformations.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Infections are usually observed during the winter and spring months. In contrast to measles, which has a high clinical attack rate among exposed susceptible individuals, only 30 to 60% of rubella-infected susceptible persons develop clinically apparent dis-ease. A major focus of concern is susceptible women of childbearing age, who carry a risk of exposure during pregnancy. Patients with primary acquired infections are conta-gious from 7 days before to 7 days after the onset of rash; congenitally infected infants may spread the virus to others for 6 months or longer after birth.

PATHOGENESIS

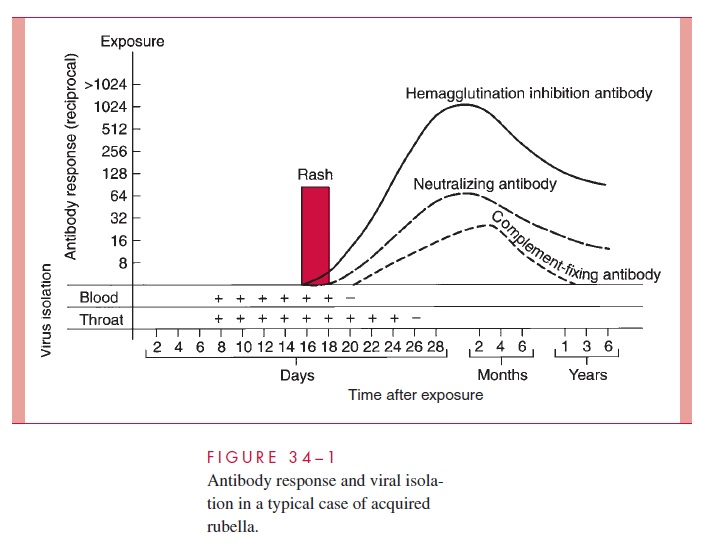

In acquired infection, the virus enters the host through the upper respiratory tract, repli-cates, and then spreads by the bloodstream to distant sites, including lymphoid tissues, skin, and organs. Viremia in these infections has been detected for as long as 8 days before to 2 days after onset of the rash, and virus shedding from the oropharynx can be detected up to 8 days after onset (Fig 34–1). Cellular immune responses and circulating virus–antibody immune complexes are thought to play a role in mediating the inflamma-tory responses to infection, such as rash and arthritis.

Congenital infection occurs as a result of maternal viremia that leads to placental in-fection and then transplacental spread to the fetus. Once fetal infection occurs, it persists chronically. Such persistence is probably related to an inability to eliminate the virus by immune or interferon-mediated mechanisms. There is too little inflammatory change in the fetal tissues to explain the pathogenesis of the congenital defects. Possibilities include placental and fetal vasculitis with compromise of fetal oxygenation, chronic viral infec-tion of cells leading to impaired mitosis, cellular necrosis, and induction of chromosomal breakage. Any or all of these factors may operate at a critical stage of organogenesis to induce permanent defects. Viral persistence with circulating virus–antibody immune complexes may evoke inflammatory changes postnatally and produce continuing tissue damage.

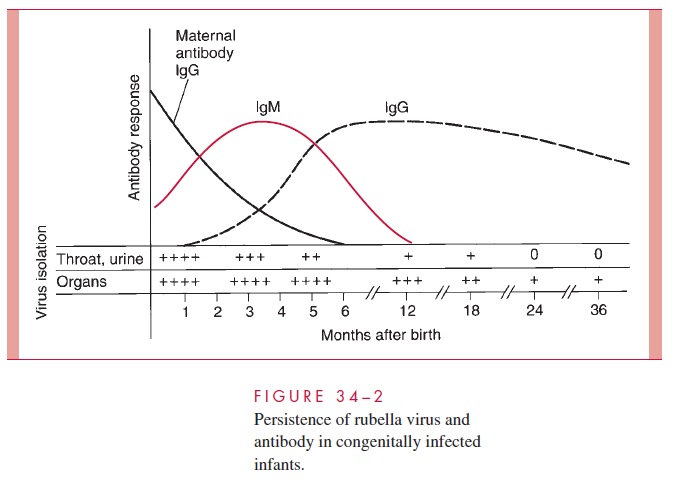

After birth, affected infants continue to excrete the virus in the throat, urine, and in-testinal tract (Fig 34–2). Virus may be isolated from virtually all tissues in the first few weeks of life. Shedding of virus in the throat and urine, which persists for at least 6 months in most cases, has been known to continue for 30 months. Virus has also been isolated from lens tissue removed 3 to 4 years later. These observations underscore the fact that such infants are important reservoirs in perpetuating virus transmission. The pro-longed virus shedding is somewhat puzzling; it does not represent a typical example of immunologic tolerance. The affected infants are usually able to produce circulating IgM and IgG antibodies to the virus (see Fig 34–2), although antibodies may decrease to unde-tectable levels after 3 to 4 years. Many infants show evidence of depressed rubella virus-specific cell-mediated immunity during the first year of life.

PATHOLOGY

Because postnatally acquired disease is usually mild, little is known about its pathology. Mononuclear cell inflammatory changes can be observed in tissues, and viral antigen can be detected in the same sites (eg, skin and synovial fluid). Congenital infections are character-ized primarily by the various malformations. Necrosis of tissues such as myocardium and vascular endothelium may also be seen, and quantitative studies suggest a decrease in cell quantity in affected organs. In severe cases, normal calcium deposition in the metaphyses of long bones is delayed, sometimes referred to as a “celery stalk” appearance on a radiograph.

IMMUNITY

After infection the serum antibody titer rises, reaching a peak within 2 to 3 weeks of on-set. Natural infection also results in the production of specific secretory IgA antibodies in the respiratory tract. Immunity to disease is nearly always lifelong; however, reexposure can lead to transient respiratory tract infection, with an anamnestic rise in IgG and secre-tory IgA antibodies, but without resultant viremia or illness.

Related Topics