Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Preoperative Nursing Management

Preparation for Surgery

Preparation for Surgery

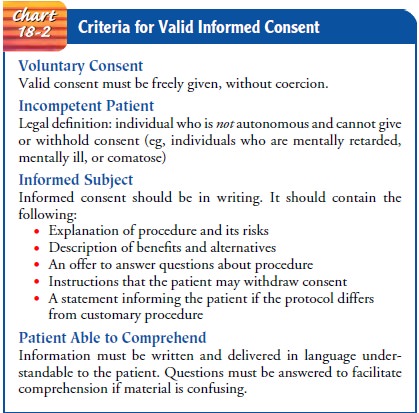

INFORMED CONSENT

Voluntary

and written informed consent from

the patient is necessary before nonemergent surgery can be performed. Such

written consent protects the patient from unsanctioned surgery and protects the

surgeon from claims of an unauthorized oper-ation. In the best interests of all

parties concerned, sound med-ical, ethical, and legal principles are followed.

The nurse may ask the patient to sign the form and may witness the patient’s

signature. It is the physician’s responsibility to provide appro-priate

information. Chart 18-2 lists the criteria for a valid in-formed consent.

Many ethical principles are integral to informed consent. Before the patient signs the consent form, the surgeon must provide a clear and simple explanation of what the surgery will entail. The surgeon must also inform the patient of the ben-efits, alternatives, possible risks, complications, disfigurement, disability, and removal of body parts as well as what to expect in the early and late postoperative periods. If the patient needs additional information to make his or her decision, the nurse notifies the physician about this. Also, the nurse ascertains that the consent form has been signed before administering psycho-active premedication, because the consent may not be valid if it was obtained while the patient was under the influence of medications that can affect judgment and decision-making capacity. Informed consent is necessary in the following circumstances:

• Invasive procedures, such as a surgical

incision, a biopsy, a cystoscopy, or paracentesis

• Procedures requiring sedation and/or

anesthesia

• A nonsurgical procedure, such as an

arteriography, that car-ries more than slight risk to the patient

• Procedures involving radiation

The patient personally signs the consent if he or she is of legal age and is mentally capable. When the patient is a minor or un-conscious or incompetent, permission must be obtained from a responsible family member (preferably next of kin) or legal guardian. An emancipated minor (married or independently earning his or her own living) may sign his or her own consent form. State regulations and agency policy must be followed.

In an

emergency, it may be necessary for the surgeon to operate as a lifesaving

measure without the patient’s informed consent. Every effort, however, must be

made to contact the patient’s family. In such a situation, contact can be made

by telephone, telegram, fax, or other electronic means.

When

the patient has doubts and has not had the opportunity to investigate

alternative treatments, a second opinion may be re-quested. No patient should

be urged or coerced to sign an oper-ative permit. Refusing to undergo a

surgical procedure is a person’s legal right and privilege. However, such

information must be documented and relayed to the surgeon so that other

arrangements can be made. For example, additional explanations may be provided

to the patient and family, or the surgery may be rescheduled.

The

consent process can be improved by providing audio-visual materials to

supplement discussion, by ensuring that the wording of the consent form is

understandable, and by using other strategies and resources as needed to help

the patient understand its content.

ASSESSMENT OF HEALTH FACTORS THAT AFFECT PATIENTS PREOPERATIVELY

The

overall goal in the preoperative period is for the patient to have as many

positive health factors as possible. Every attempt is made to stabilize those

conditions that otherwise hinder a smooth recovery. When negative factors

dominate, the risks of surgery and postoperative complications increase.

Before

any surgical treatment is initiated, a health history is obtained, a physical

examination is performed during which vital signs are noted, and a database is

established for future compar-isons (Meeker & Rothrock, 1999). During the

physical exami-nation, many factors are considered that have the potential to

affect the patient undergoing surgery. Health care providers should be alert

for signs of abuse that can occur at all ages and to men and women from all

socioeconomic, ethnic, and cultural groups (Little, 2000; Marshall, Benton

& Brazier, 2000). Findings need to be reported accordingly.

Blood

tests, x-rays, and other diagnostic tests are prescribed when specifically

indicated by information obtained from a thor-ough history and physical

examination (King, 2000). These pre-liminary contacts with the health care team

provide the patient with opportunities to ask questions and to become

acquainted with those who may be providing care during and after surgery.

Nutritional and Fluid Status

Optimal

nutrition is an essential factor in promoting healing and resisting infection

and other surgical complications (Braunschweig, Gomez & Sheean, 2000).

Assessment of a patient’s nutritional sta-tus provides information on obesity,

undernutrition, weight loss, malnutrition, deficiencies in specific nutrients,

metabolic abnor-malities, the effects of medications on nutrition, and special

prob-lems of the hospitalized patient (Quinn, 1999). Nutritional needs may be

determined by measurement of body mass index and waist circumference (National

Institutes of Health, 2000).

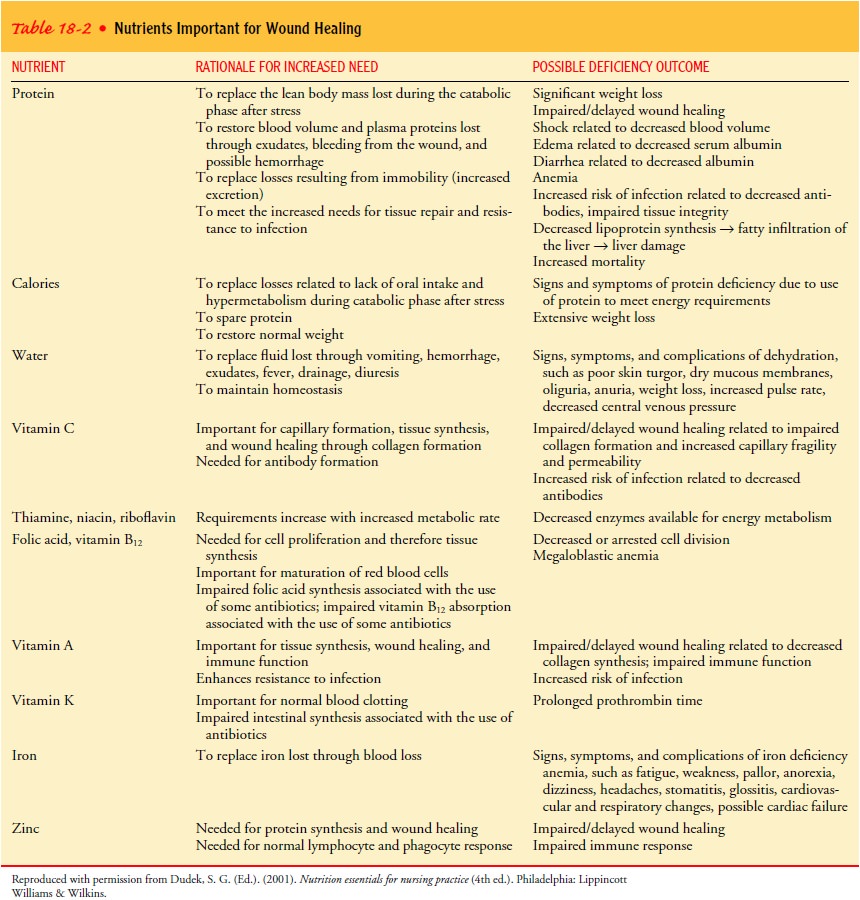

Any

nutritional deficiency, such as malnutrition, should be corrected before

surgery so that enough protein is available for tissue repair (King, 2000;

Russell, Williams & Bulstrode, 2000). The nutrients needed for wound

healing are summarized in Table 18-2.

Dehydration,

hypovolemia, and electrolyte imbalances can lead to significant problems in

patients with comorbid medical conditions or in elderly patients. The severity

of fluid and electro-lyte imbalances is often difficult to determine. Mild

volume de-ficits may be treated during surgery; however, additional time may be

needed to correct pronounced fluid and electrolyte deficits to promote the best

possible preoperative condition.

Drug or Alcohol Use

People

who abuse drugs or alcohol frequently deny or attempt to hide it. In such

situations, the nurse who is obtaining the patient’s health history needs to

ask frank questions with patience, care, and a nonjudgmental attitude.

Because

acutely intoxicated persons are susceptible to injury, surgery is postponed in

these patients if possible. If emergency surgery is required, local, spinal, or

regional block anesthesia is used for minor surgery. Otherwise, to prevent

vomiting and po-tential aspiration, a nasogastric tube is inserted before

adminis-tering general anesthesia.

The

person with a history of chronic alcoholism often suffers from malnutrition and

other systemic problems that increase the surgical risk. Additionally, alcohol

withdrawal delirium (delirium tremens) may be anticipated up to 72 hours after

alcohol with-drawal. Delirium tremens is associated with a significant

mortal-ity rate when it occurs postoperatively.

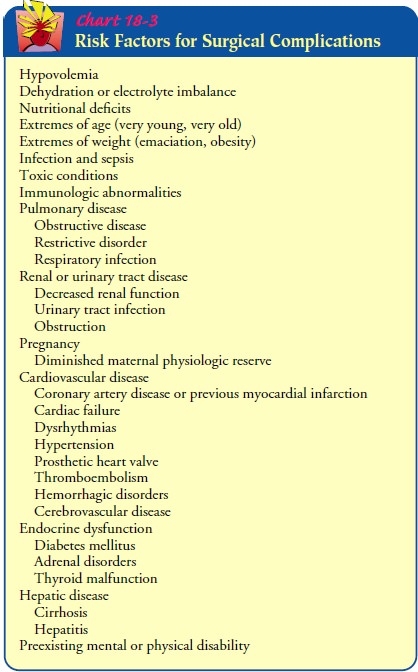

Chart

18-3 gives more information about risk factors that may lead to complications.

Respiratory Status

The

goal for potential surgical patients is optimal respiratory function. Patients

are taught breathing exercises and use of an incentive spirometer if indicated.

Because adequate ventilation is potentially compromised during all phases of

surgical treat-ment, surgery is usually postponed when the patient has a

respi-ratory infection. Patients with underlying respiratory disease (eg,

asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) are assessed carefully for

current threats to their pulmonary status. Patients’ use of medications that

may affect recovery is also assessed (King, 2000; Smetana, 1999).

Patients

who smoke are urged to stop 2 months before sur-gery (King, 2000), although

many do not do so. These patients should be counseled to stop smoking at least

24 hours prior to surgery. Research suggests that counseling has a positive

effect on the patient’s smoking behavior 24 hours preceding surgery, helping

reduce the potential for adverse effects associated with smoking such as

increased airway reactivity, decreased muco-ciliary clearance, as well as

physiologic changes in the cardio-vascular and immune systems (Shannon-Cain,

Webster & Cain, 2002).

Cardiovascular Status

The goal in preparing any patient for surgery is to ensure a well-functioning cardiovascular system to meet the oxygen, fluid, and nutritional needs of the perioperative period. If the patient has uncontrolled hypertension, surgery may be postponed until the blood pressure is under control.

Because

cardiovascular disease increases the risk for complica-tions, patients with

these conditions require greater-than-usual diligence during all phases of

nursing management and care (King, 2000). Depending on the severity of the

symptoms, surgery may be deferred until medical treatment can be instituted to

improve the patient’s condition. At times, surgical treatment can be mod-ified

to meet the cardiac tolerance of the patient. For example, in a patient with

obstruction of the descending colon and coronary artery disease, a temporary

simple colostomy may be performed rather than a more extensive colon resection

that would require a prolonged period of anesthesia.

Hepatic and Renal Function

The

presurgical goal is optimal function of the liver and urinary systems so that

medications, anesthetic agents, body wastes, and toxins are adequately

processed and removed from the body.

The

liver is important in the biotransformation of anesthetic compounds. Therefore,

any disorder of the liver has an effect on how anesthetic agents are

metabolized. Because acute liver disease is associated with high surgical

mortality, preoperative improve-ment in liver function is a goal. Careful

assessment is made with the help of various liver function tests.

Because the kidneys are involved in excreting anesthetic drugs and their metabolites and because acid–base status and metabolism are also important considerations in anesthesia administration, surgery is contraindicated when a patient has acute nephritis, acute renal insufficiency with oliguria or anuria, or other acute renal problems. The exception is surgery that is performed as a lifesav-ing measure or that is necessary to improve urinary function, as in the case of an obstructive uropathy.

Endocrine Function

The

patient with diabetes who is undergoing surgery is at risk for hypoglycemia and

hyperglycemia. Hypoglycemia may develop during anesthesia or postoperatively

from inadequate carbohy-drates or from excessive administration of insulin.

Hyperglycemia, which may increase the risk for surgical wound infection, may

re-sult from the stress of surgery, which may trigger increased levels of

catecholamine. Other risks are acidosis and glucosuria. Although the surgical

risk in the patient with controlled diabetes is no greater than in the

nondiabetic patient, the goal is to maintain the blood glucose level at less

than 200 mg/dL. Frequent monitoring of blood glucose levels is important

before, during, and after surgery.

Patients

who have received corticosteroids are at risk for adre-nal insufficiency.

Therefore, the use of corticosteroids for any purpose during the preceding year

must be reported to the anes-thesiologist or anesthetist and surgeon.

Additionally, the patient is monitored for signs of adrenal insufficiency.

Patients

with uncontrolled thyroid disorders are at risk for thy-rotoxicosis (with hyperthyroid

disorders) and respiratory failure (with hypothyroid disorders). Therefore, the

patient is assessed for a history of these disorders.

Immune Function

An

important function of the preoperative assessment is to de-termine the

existence of allergies, including the nature of previous allergic reactions. It

is especially important to identify and docu-ment any sensitivity to

medications and past adverse reactions to these agents. The patient is asked to

identify any substances that precipitated previous allergic reactions,

including medications, blood transfusions, contrast agents, latex, and food

products, and to describe the signs and symptoms produced by these substan-ces.

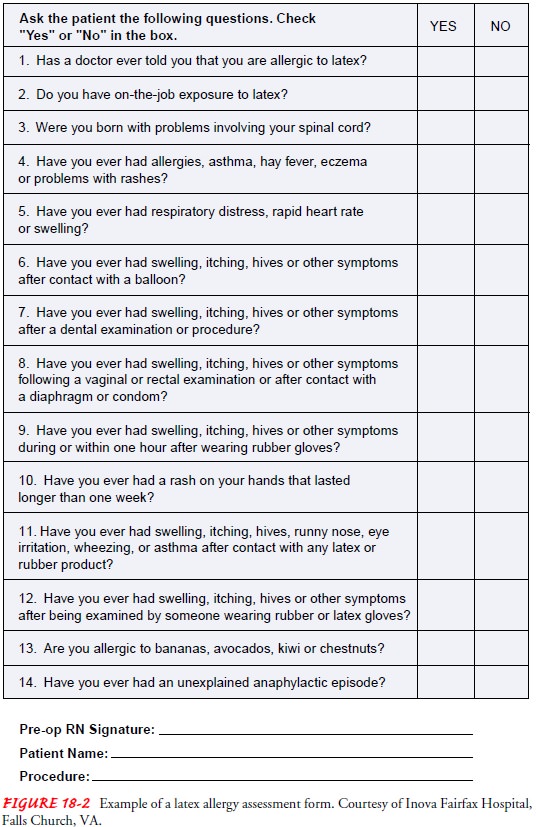

A sample latex allergy screening questionnaire is shown in Figure 18-2.

Immunosuppression

is common with corticosteroid therapy, renal transplantation, radiation

therapy, chemotherapy, and dis-orders affecting the immune system, such as

acquired immuno-deficiency syndrome (AIDS) and leukemia. The mildest symptoms

or slightest temperature elevation must be investigated. Because pa-tients who

are immunosuppressed are highly susceptible to infec-tion, great care is taken

to ensure strict asepsis.

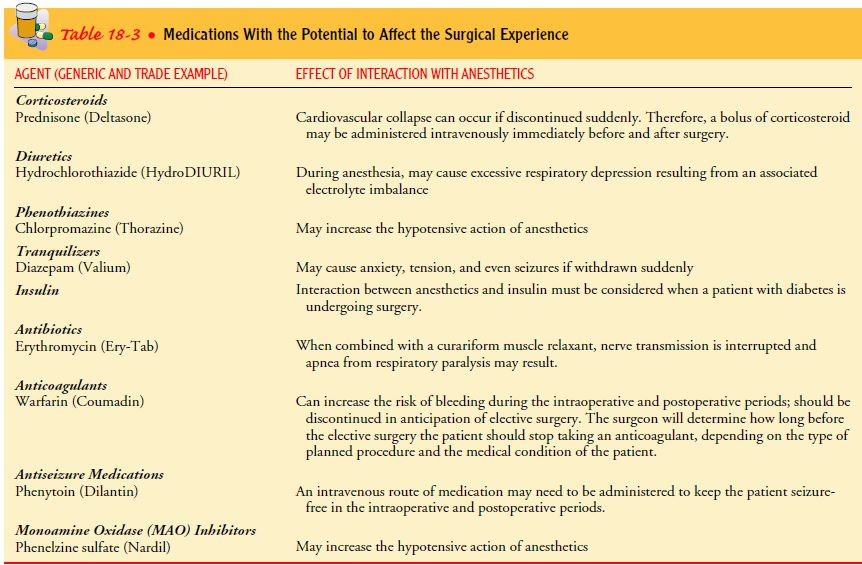

Previous Medication Use

A

medication history is obtained from each patient because of the possible

effects of medications on the patient’s perioperative and perianesthesia course

and the possibility of drug interactions (Quinn, 1999). Any medication the

patient is using or has used in the past is documented, including

over-the-counter (OTC) preparations and herbal agents and the frequency with

which they are used. Potent medications have an effect on physiologic

functions; interactions of such medications with anesthetic agents can cause

serious problems, such as arterial hypotension and cir-culatory collapse.

The

potential effects of prior medication therapy are evaluated by the

anesthesiologist or anesthetist, who considers the length of time the patient

has used the medications, the physical condition of the patient, and the nature

of the proposed surgery. Medica-tions that cause particular concern are listed

in Table 18-3.

Many

patients take self-prescribed or OTC medications in ad-dition to those listed

in Table 18-3. Aspirin is a common OTC medication prescribed by physicians or

taken independently by patients to prevent myocardial infarction, stroke, and

other dis-orders (Karch, 2002). Because of the effects of aspirin or other OTC

medications and possible interactions with other medica-tions and anesthetic

agents, it is important to ask a patient about their use. The information is

noted in the patient’s chart and con-veyed to the anesthesiologist or

anesthetist and surgeon.

The use of herbal medications is widespread among patients. Approximately 15 million Americans report their use (Ang-Lee, Moss & Yuan, 2001; Karch, 2002; Lyons, 2002). Patients with chronic illnesses may be using herbal medications to supplement their prescribed medications or in place of them.

Certain herbal medications, such as echinacea, ephedra, garlic (Allium sativum), ginkgo, ginseng, kava kava (Piper methysticum), St. John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum), licorice (Glycyhiza glabra), and valerian (Valeriana officinalis) have been

identified as the most commonly used herbal medications that may cause concern

during the peri-operative period (Ang-Lee, Moss & Yuan, 2001; Kuhn, 1999;

Lyons, 2002). Because of the potential effects of herbal medica-tions on

coagulation and potential interactions with other med-ications, the nurse must

ask surgical patients explicitly about the use of these agents, document their

use, and inform the surgical team and anesthesiologist or anesthetist (Brumly,

2000).

Psychosocial Factors

All

patients have some type of emotional reaction before any sur-gical procedure,

be it obvious or hidden, normal or abnormal. For example, preoperative anxiety

may be an anticipatory response to an experience the patient views as a threat

to his or her custom-ary role in life, body integrity, or life itself. Psychological

distress directly influences body functioning. Therefore, it is imperative to

identify any anxiety the patient is experiencing.

By taking a careful health history, the nurse elicits patient con-cerns that can have a bearing on the course of the surgical expe-rience (Quinn, 1999). Undoubtedly, a patient about to undergo surgery is faced with various fears, including fears of the unknown, of death, of anesthesia, pain, or cancer.

Concerns about loss of work time, loss of job, increased responsibilities or burden on family members, and the threat of permanent incapacity further contribute

to the emotional strain created by the prospect of surgery. Less obvious

concerns may occur because of previous ex-periences with the health care system

and people the patient has known with the same condition.

People

express fear in different ways. For example, one patient may repeatedly ask a

lot of questions, even though answers were given previously. Another person may

withdraw, deliberately avoiding communication, perhaps by reading or watching

televi-sion. Still others may talk about trivialities. Consequently, the nurse

must be empathetic, listen well, and provide information that helps alleviate

concerns.

An

important outcome of the psychosocial assessment is the determination of the

extent and role of the patient’s support net-work. The value and reliability of

all available support systems are assessed. Other information, such as usual

level of functioning and typical daily activities, may assist in the patient’s

care and re-habilitation plans. Assessing the patient’s readiness to learn and

determining the best approach to maximize comprehension will provide the basis

for preoperative patient education.

Spiritual and Cultural Beliefs

Spiritual

beliefs play an important role in how people cope with fear and anxiety.

Regardless of the patient’s religious affiliation, spiritual beliefs can be as

therapeutic as medication. Every at-tempt must be made to help the patient obtain

the spiritual help that he or she requests. Faith has great sustaining power.

Thus, the beliefs of each patient should be respected and supported. Somenurses

avoid the subject of a clergy visit lest the suggestion alarm the patient.

Asking if the patient’s spiritual advisor knows about the impending surgery is

a caring, nonthreatening approach.

Showing

respect for a patient’s cultural values and beliefs fa-cilitates rapport and

trust. Some areas of assessment include iden-tifying the ethnic group to which

the patient relates and the customs and beliefs the patient holds about illness

and health care providers. For example, patients from some cultural groups are

unaccustomed to expressing feelings openly. Nurses need to consider this

pattern of communication when assessing pain. As a sign of respect, people from

other cultural groups may not make direct eye contact with others. The nurse

needs to know that this lack of eye contact is not avoidance or a lack of

interest.

Perhaps

the most valuable skill at the nurse’s disposal is listen-ing carefully to the

patient, especially when obtaining the history. Invaluable information and

insights may be gained by engaging in conversation and using communication and

interviewing skills. An unhurried, understanding, and caring nurse invites

confidence on the part of the patient.

Related Topics