Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Principles and Practices of Rehabilitation

Nursing Process: The Patient With Impaired Skin Integrity

NURSING PROCESS: THE PATIENT WITH IMPAIRED SKIN

INTEGRITY

An estimated 1.5 to 3 million patients develop pressure ulcers an-nually

(Mayo Clinic Rochester, 2001). Both prevention and treat-ment of pressure

ulcers are costly in terms of health care dollars and quality of life for

patients at risk. Because the cost in terms of pain and suffering for a person

with a pressure ulcer cannot be quanti-fied, all possible efforts should be

made to prevent skin breakdown.

Patients confined to bed for long periods, patients with motor or

sensory dysfunction, and patients who experience muscular at-rophy and

reduction of padding between the overlying skin and the underlying bone are

prone to pressure ulcers. Pressure ulcers are localized areas of infarcted soft

tissue that occur when pressure applied to the skin over time is greater than

normal capillary clo-sure pressure, which is about 32 mm Hg. Critically ill

patients have a lower capillary closure pressure and are at greater risk for

pressure ulcers. The initial sign of pressure is erythema (redness of the skin)

caused by reactive hyperemia, which normally resolves in less than 1 hour.

Unrelieved pressure results in tissue ischemia or anoxia. The cutaneous tissues

become broken or destroyed, leading to progressive destruction and necrosis of

underlying soft tissue, and the resulting pressure ulcer is painful and slow to

heal.

Assessment

Immobility, impaired sensory perception or

cognition, decreased tissue perfusion, decreased nutritional status, friction

and shear forces, increased moisture, and age-related skin changes all

con-tribute to the development of pressure ulcers.

IMMOBILITY

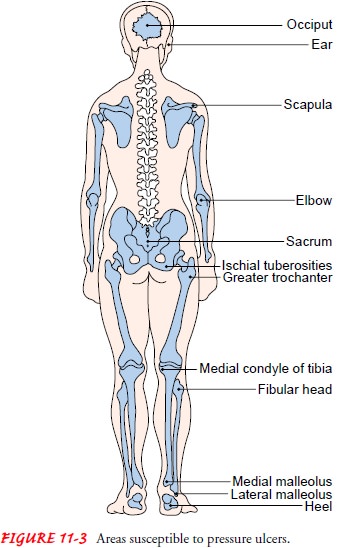

When a person is immobile and inactive, pressure is

exerted on the skin and subcutaneous tissue by objects on which the person

rests, such as a mattress, chair seat, or cast. The development of pressure

ulcers is directly related to the duration of immobility: if pressure continues

long enough, small vessel thrombosis and tis-sue necrosis occur, and a pressure

ulcer results. Weight-bearing bony prominences are most susceptible to pressure

ulcer devel-opment because they are covered only by skin and small amounts of

subcutaneous tissue. Susceptible areas include the sacrum and coccygeal areas,

ischial tuberosities (especially in people who sit for prolonged periods),

greater trochanter, heel, knee, malleolus, medial condyle of the tibia, fibular

head, scapula, and elbow (Fig. 11-3).

IMPAIRED SENSORY PERCEPTION OR COGNITION

Patients with sensory loss, impaired level of consciousness, or

paralysis may not be aware of the discomfort associated with pro-longed

pressure on the skin and, therefore, may not change their position themselves

to relieve the pressure. This prolonged pres-sure impedes blood flow, reducing

nourishment of the skin and underlying tissues. A pressure ulcer may develop in

a short period.

DECREASED TISSUE PERFUSION

Any condition that

reduces the circulation and nourishment of the skin and subcutaneous tissue

(altered peripheral tissue perfu-sion) increases the risk of pressure ulcer

development. Patients with diabetes mellitus experience an alteration in

microcircula-tion. Similarly, patients with edema have impaired circulation and

poor nourishment of the skin tissue. Obese patients have large amounts of

poorly vascularized adipose tissue, which is sus-ceptible to breakdown.

DECREASED NUTRITIONAL STATUS

Nutritional

deficiencies, anemias, and metabolic disorders also contribute to pressure

ulcer development. Anemia, regardless of its cause, decreases the blood’s

oxygen-carrying ability and pre-disposes a patient to pressure ulcer formation.

Patients who have low protein levels or who are in a negative nitrogen balance

ex-perience tissue wasting and inhibited tissue repair. Serum albu-min is a

sensitive indicator of protein deficiency; serum albumin levels of less than 3

g/mL are associated with hypoalbuminemic tissue edema and increased risk of

pressure ulcers. Specific nutri-ents, such as vitamin C and trace minerals, are

needed for tissue maintenance and repair.

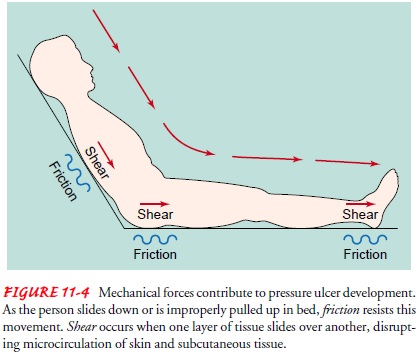

FRICTION AND SHEAR

Mechanical forces also contribute to the development of pres-sure

ulcers. Friction is the resistance to movement that occurs when two surfaces

are moved across each other. Shear is created by the interplay of gravitational

forces (forces that push the body down) and friction. When shear occurs, tissue

layers slide over one another, blood vessels stretch and twist, and the

microcir-culation of the skin and subcutaneous tissue is disrupted. Evi-dence

of deep tissue damage may be slow to develop and maypresent through the

development of a draining tract. The sacrum and heels are most susceptible to

the effects of shear. Pressure ul-cers from friction and shear occur when the

patient slides down in bed (Fig. 11-4) or when the patient is moved or

positioned improperly (eg, dragged up in bed). Spastic muscles and paraly-sis

increase the patient’s vulnerability to pressure ulcers related to friction and

shear.

INCREASED MOISTURE

Prolonged contact with moisture from perspiration, urine, feces, or

drainage produces maceration (softening) of the skin. The skin reacts to the

caustic substances in the excreta or drainage and be-comes irritated. Moist,

irritated skin is more vulnerable to pres-sure breakdown. Once the skin breaks,

the area is invaded by microorganisms (eg, streptococci, staphylococci, Pseudomonasaeruginosa, Escherichia coli),

and infection occurs. Foul-smellinginfectious drainage is present. The lesion

may enlarge and allow a continuous loss of serum, which may further deplete the

body of essential protein needed for tissue repair and maintenance. The lesion

may continue to enlarge and extend deep into the fascia, muscle, and bone, with

multiple sinus tracts radiating from the pressure ulcer. With extensive

pressure ulcers, systemic infections may develop, frequently from gram-negative

organisms.

Gerontologic Considerations

In older adults, the

skin has diminished epidermal thickness, der-mal collagen, and tissue

elasticity. The skin is drier as a result of diminished sebaceous and sweat

gland activity. Cardiovascular changes result in decreased tissue perfusion.

Muscles atrophy, and bone structures become prominent. Diminished sensory

percep-tion and reduced ability to reposition oneself contribute to pro-longed

pressure on the skin. Therefore, the older adult is more susceptible to

pressure ulcers, which cause pain and suffering and reduce quality of life

(Agency for Health Care Policy and Research [AHCPR], 1994).

ADDITIONAL RISK FACTORS

In assessing the patient for potential risk for pressure ulcer devel-opment, the nurse assesses the patient’s mobility, sensory per-ception, cognitive abilities, tissue perfusion, nutritional status, friction and shear forces, sources of moisture on the skin, and age. The nurse

•

Assesses total skin condition at least twice a day

•

Inspects each pressure site for erythema

•

Assesses areas of erythema for blanching response

•

Palpates the skin for increased warmth

•

Inspects for dry skin, moist skin, breaks in skin

•

Notes drainage and odor

•

Evaluates level of mobility

•

Notes restrictive devices (eg, restraints, splints)

•

Evaluates circulatory status (eg, peripheral

pulses, edema)

•

Assesses neurovascular status

•

Determines presence of incontinence

•

Evaluates nutritional and hydration status

•

Reviews the patient’s record for laboratory

studies, includ-ing hematocrit, hemoglobin, electrolytes, albumin,

trans-ferrin, and creatinine

•

Notes present health problems

•

Reviews current medications

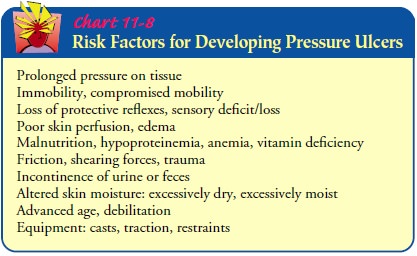

Scales such as the

Braden or Norton scale may be used to fa-cilitate systematic assessment and

quantification of a patient’s risk for pressure ulcer, although the nurse needs

to recognize that the reliability of these scales is not well established. They

tend to over-estimate those at risk and may promote unwarranted use of costly

preventive equipment. See Chart 11-8 for a list of risk factors for development

of pressure ulcers.

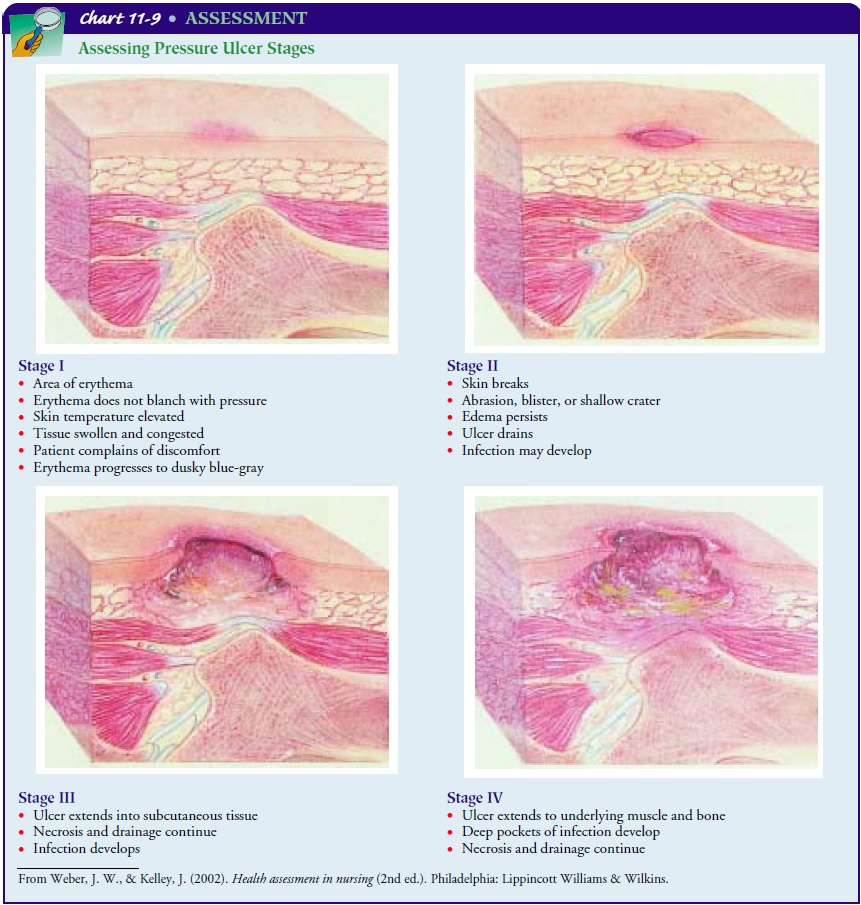

If a pressure area is noted, the nurse notes its size and location and

may use a grading system to describe its severity (see Chart 11-9). Generally,

a stage I pressure ulcer is an area of nonblanch-able erythema, tissue

swelling, and congestion, and the patient complains of discomfort. The skin

temperature is elevated be-cause of the increased vasodilation. The redness

progresses to a dusky, cyanotic blue-gray appearance, which is the result of

skin capillary occlusion and subcutaneous weakening.

A stage II pressure ulcer exhibits a break in the skin through the

epidermis or the dermis. An abrasion, blister, or shallow crater may be seen.

Necrosis occurs along with venous sludging and throm-bosis and edema with

cellular extravasation and infiltration.

A stage III pressure ulcer extends into the subcutaneous tissues.

Clinically, a deep crater with or without undermining of adjacent tissues is

noted.

A stage IV pressure ulcer extends into the

underlying structures, including the muscle and, possibly, the bone. The skin

lesion may appear insignificant when in reality, beneath the small surface

ulcer is a large undermined area of necrotic tissue.

The appearance of

purulent drainage or foul odor suggests an infection. With an extensive

pressure ulcer, deep pockets of infec-tion are often present. Drying and

crusting of exudate may be present. Infection of a pressure ulcer may advance

to osteomyelitis, pyarthrosis (pus formation within a joint cavity), sepsis,

and septic shock.

Nursing Diagnosis

Based on the assessment

data, the nursing diagnoses may include the following:

· Risk for impaired skin

integrity

· Impaired skin integrity

(related to immobility, decreased sensory perception, decreased tissue

perfusion, decreased nutritional status, friction and shear forces, increased

mois-ture, or advanced age)

Planning and Goals

The major goals for the

patient may include relief of pressure, improved mobility, improved sensory

perception, improved tis-sue perfusion, improved nutritional status, minimized

friction and shear forces, dry surfaces in contact with skin, and healing of

pressure ulcer, if present.

Nursing Interventions

RELIEVING PRESSURE

Frequent changes of position are needed to relieve and redistrib-ute the

pressure on the patient’s skin and to prevent prolonged reduced blood flow to

the skin and subcutaneous tissues. This can be accomplished by teaching the

patient to change position or by turning and repositioning the patient. The patient’s

family mem-bers should be taught how to position and turn the patient at home

to prevent pressure ulcers. Shifting weight allows the blood to flow into the

ischemic areas and helps the tissues recover from the effects of pressure.

Thus, the patient should be cared for as follows:

•

Turned and repositioned at 1-hour to 2-hour

intervals

•

Encouraged to shift weight actively every 15

minutes

POSITIONING THE PATIENT

The patient should be

positioned laterally, prone, and dorsally in sequence unless a position is not

tolerated or is contraindicated. The recumbent position is preferred to the

semi-Fowler’s posi-tion because of increased supporting body surface area in

this po-sition. In addition to regular turning, there should be small shifts of

body weight, such as repositioning of an ankle, elbow, or shoulder. The skin is

inspected at each position change and as-sessed for temperature elevation. If

redness or heat is noted or if the patient complains of discomfort, pressure on

the area must be relieved.

Another way to relieve

pressure over bony prominences is the bridging technique, accomplished through

the correct position-ing of pillows. Just as a bridge is supported on pillars

to allow traf-fic to move underneath, so can the body be supported by pillows

to allow for space between bony prominences and the mattress. A pillow or

commercial heel protector may be used to support the heels off the bed when the

patient is supine. Placing pillows su-perior and inferior to the sacrum

relieves sacral pressure. Sup-porting the patient in a 30-degree side-lying

position avoids pressure on the trochanter. In the aging patient, frequent

small shifts of body weight may be effective. Placing a small rolled towel or

sheepskin under a shoulder or hip will allow a return of blood flow to the skin

in the area on which the patient is sitting or lying. The towel or sheepskin is

moved around the patient’s pressure points in a clockwise fashion.

USING PRESSURE-RELIEVING DEVICES

At times, special

equipment and beds may be needed to help re-lieve the pressure on the skin.

These are designed to provide sup-port for specific body areas or to distribute

pressure evenly.

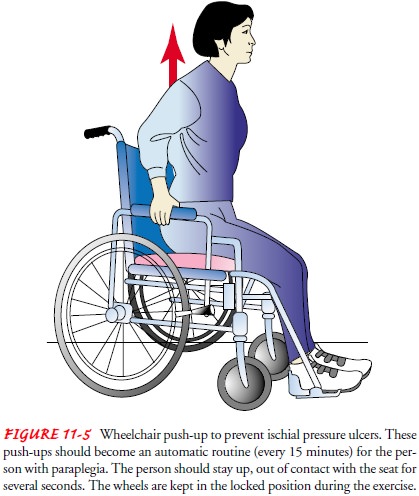

Patients sitting in wheelchairs for prolonged periods should have

wheelchair cushions fitted and adjusted on an individualized basis, using

pressure measurement techniques as a guide to selec-tion and fitting. The aim

is to redistribute pressure away from areas at risk for ulcers, but no cushion

is able to eliminate exces-sive pressure completely. The patient should be

reminded to shift weight frequently and to rise for a few seconds every 15

minutes while sitting in a chair (Fig. 11-5).

Static support devices (such as high-density foam, air, or liq-uid mattress overlays) distribute pressure evenly by bringing more of the patient’s body surface into contact with the supporting sur-face. Gel-type flotation pads and air-fluidized beds reduce pres-sure. The weight of a body floating on a fluid system is evenly distributed over the entire supporting surface (according to Pas-cal’s law). Therefore, as the patient’s body sinks into the fluid, additional surface becomes available for weight bearing, body weight per unit area is decreased, and there is less pressure on the body parts.

Soft, moisture-absorbing padding is also useful because the softness and

resilience of padding provides for more even distrib-ution of pressure and the

dissipation and absorption of moisture, along with freedom from wrinkles and

friction. Bony promi-nences may be protected by gel pads, sheepskin padding, or

soft foam rubber beneath the sacrum, the trochanters, heels, elbows, scapulae,

and back of the head when there is pressure on the sites.

Specialized beds have been designed to prevent pressure on the skin.

Air-fluidized beds float the patient. Dynamic support sur-faces, such as low

air-loss pockets, alternately inflate and deflate sections to change support

pressure for very high-risk patients who are critically ill and debilitated and

cannot be repositioned to relieve pressure. Oscillating or kinetic beds change

pressure by means of rocking movements of the bed that redistribute the

pa-tient’s weight and stimulate circulation. These beds are frequently used

with patients who have injuries due to multiple trauma.

IMPROVING MOBILITY

The patient is

encouraged to remain active and is ambulated whenever possible. When sitting,

the patient is reminded to change positions frequently to redistribute weight.

Active and passive exercises increase muscular, skin, and vascular tone. Ac-tivity

stimulates circulation, which relieves tissue ischemia, the forerunner of

pressure ulcers. For the patient at risk for pressure ulcers, turning and

exercise schedules are essential: repositioning must occur around the clock.

IMPROVING SENSORY PERCEPTION

The nurse helps the

patient recognize and compensate for altered sensory perception. Depending on

the origin of the alteration (eg, decreased level of consciousness, spinal cord

lesion), specific interventions are selected. Strategies to improve cognition

and sensory perception may include stimulating the patient to in-crease

awareness of self in the environment, encouraging the pa-tient to participate

in self-care, or supporting the patient’s efforts toward active compensation

for loss of sensation (eg, a paraplegic patient lifting up from the sitting

position every 15 minutes). When decreased sensory perception exists, the

patient and care-giver are taught to inspect potential pressure areas visually

every morning and evening, using a mirror if necessary, for evidence of

pressure ulcer development.

IMPROVING TISSUE PERFUSION

Exercise and

repositioning improve tissue perfusion. Massage of erythematous areas is

avoided because damage to the capillaries and deep tissue may occur.

In patients who have evidence of compromised peripheral cir-culation

(eg, edema), positioning and elevation of the edematous body part to promote

venous return and diminish congestion im-prove tissue perfusion. In addition,

the nurse or family must be alert to environmental factors (eg, wrinkles in

sheets, pressure of tubes) that may contribute to pressure on the skin and

dimin-ished circulation and remove the source of pressure.

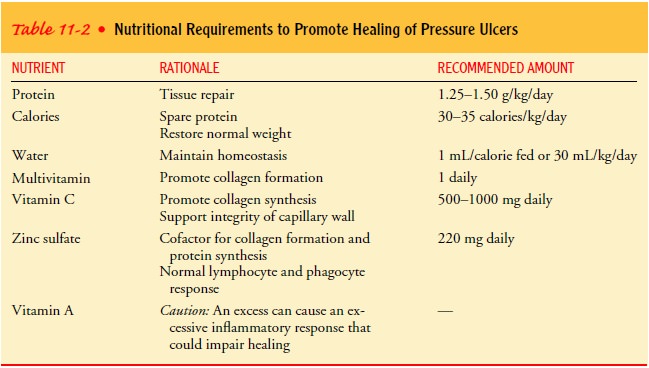

IMPROVING NUTRITIONAL STATUS

The patient’s nutritional status must be adequate, and a positive nitrogen

balance must be maintained, because pressure ulcers de-velop more quickly and

are more resistant to treatment in patients with nutritional disorders. A

high-protein diet with protein sup-plements may be helpful. Iron preparations

may be necessary to raise the hemoglobin concentration so that tissue oxygen

levels can be maintained within acceptable limits. Ascorbic acid (vitamin C) is

necessary for tissue healing. Other nutrients associated with healthy skin

include vitamin A, B vitamins, zinc, and sulfur. With balanced nutrition and

hydration, the skin is able to remain healthy, and damaged tissues can be

repaired (Table 11-2).To assess nutritional status response to therapeutic

strategies, the nurse monitors the patient’s hemoglobin, albumin, and body

weight weekly.

REDUCING FRICTION AND SHEAR

Shear occurs when the

patient is pulled, is allowed to slump, or moves by digging heels or elbows

into the mattress. Raising the head of the bed by even a few centimeters

increases the shearing force over the sacral area; therefore, the semireclining

position is avoided in patients at risk. Proper positioning with adequate

sup-port is also important when a patient is sitting in a chair. Poly-ester

sheepskin pads are thought to reduce shear and friction and may be used with

at-risk patients.

MINIMIZING IRRITATING MOISTURE

Continuous moisture on the skin must be prevented by meticu-lous

hygienic measures. Perspiration, urine, stool, and drainage must be removed

from the skin promptly. The soiled skin should be washed immediately with mild

soap and water and blotted dry with a soft towel. The skin may be lubricated

with a bland lotion to keep it soft and pliable. Drying agents and powders are

avoided. Topical barrier ointments (eg, petroleum jelly) may be helpful in

protecting the skin of patients who are incontinent.

Absorbent pads that wick

moisture away from the body should be used to absorb drainage. Patients who are

incontinent need to be checked regularly

and have their wet incontinence pads and linens changed promptly. Their skin

needs to be cleansed and dried promptly.

PROMOTING PRESSURE ULCER HEALING

Regardless of the stage of the pressure ulcer, the pressure on the area must be eliminated, because the ulcer will not heal until all pressure is removed. The patient must not lie or sit on the pressure ulcer, even for a few minutes. Individualized positioning and turning schedules must be written in the plan of nursing care and followed meticulously.

In addition, inadequate

nutritional status and fluid and elec-trolyte abnormalities must be corrected

to promote healing. Wounds that drain body fluids and protein place the patient

in a catabolic state and predispose to hypoproteinemia and serious secondary

infections. Protein deficiency must be corrected to heal the pressure ulcer.

Carbohydrates are necessary to “spare” the protein and to provide an energy

source. Vitamin C and trace el-ements, especially zinc, are necessary for

collagen formation and wound healing.

Stage I Pressure Ulcers

To permit healing of

stage I pressure ulcers, the pressure is re-moved to allow increased tissue

perfusion, nutritional and fluid and electrolyte balance are maintained,

friction and shear are re-duced, and moisture to the skin is avoided.

Stage II Pressure Ulcers

Stage II pressure ulcers have broken skin. In addition to measures

listed for stage I pressure ulcers, a moist environment, in which migration of

epidermal cells over the ulcer surface occurs more rapidly, should be provided

to aid wound healing. The ulcer is gently cleansed with sterile saline

solution. Use of a heat lamp to dry the open wound is avoided, as is use of

antiseptic solutions that damage healthy tissues and delay wound healing.

Semipermeable occlusive dressing, hydrocolloid wafers, or wet saline dressings

are helpful in providing a moist environment for healing and in min-imizing the

loss of fluids and proteins from the body.

Stage III and IV Pressure Ulcers

Stage III and IV pressure ulcers are characterized by extensive tissue

damage. In addition to measures listed for stage I, these advanced draining,

necrotic pressure ulcers must be cleaned (débrided) to create an area that will

heal. Necrotic, devitalized tissue favors bacterial growth, delays granulation,

and inhibits healing. Wound cleaning and dressing are uncomfortable;

there-fore, the nurse must prepare the patient for the procedure by ex-plaining

what will occur and administering prescribed analgesia.

Débridement may be accomplished by wet-to-damp dressing changes, mechanical

flushing of necrotic and infective exudate, application of prescribed enzyme

preparations that dissolve necrotic tissue, or surgical dissection. If an

eschar covers the ulcer, it is re-moved surgically to ensure a clean, vitalized

wound. Exudate may be absorbed by dressings or special hydrophilic powders,

beads, or gels. Cultures of infected pressure ulcers are obtained to guide

selection of antibiotic therapy.

After the pressure ulcer

is clean, a topical treatment is pre-scribed to promote granulation. New

granulation tissue must be protected from reinfection, drying, and damage, and

care should be taken to prevent pressure and further trauma to the area.

Dress-ings, solutions, and ointments applied to the ulcer should not dis-rupt

the healing process. Multiple agents and protocols are used to treat pressure

ulcers, but consistency is an important key to success. Objective evaluation of

the pressure ulcer (eg, measure-ment of the pressure ulcer, inspection for

granulation tissue) for response to the treatment protocol must be made every 4

to 6 days. Taking photographs at weekly intervals is a reliable strat-egy for

monitoring the healing process, which may take weeks to months to complete.

Surgical intervention is

necessary when the ulcer is extensive, when potential complications (eg,

fistula) exist, and when the ulcer does not respond to treatment. Surgical

procedures in-clude débridement, incision and drainage, bone resection, and

skin grafting.

PREVENTING RECURRENCE

Recurrence of pressure

ulcers should be anticipated; therefore, ac-tive, preventive intervention and

frequent continuing assessments are essential. The patient’s tolerance for

sitting or lying on the healed pressure area is increased gradually by

increasing the time that pressure is allowed on the area in 5- to 15-minute

incre-ments. The patient is taught to increase mobility and to follow a regimen

of turning, weight shifting, and repositioning. The pa-tient teaching plan

includes instruction on strategies to reduce the risk for development of

pressure ulcers and methods to detect, in-spect, and minimize pressure areas.

Early recognition and inter-vention are keys to long-term management of

potential impaired skin integrity.

Evaluation

EXPECTED PATIENT OUTCOMES

Expected patient

outcomes may include:

Maintains intact skin

a) Exhibits no areas of

nonblanchable erythema at bony prominences

b) Avoids massage of bony

prominences

c) Exhibits no breaks in

skin

Limits pressure on bony prominences

a) Changes position every 1

to 2 hours

b) Uses bridging techniques

to reduce pressure

c) Uses special equipment

as appropriate

d) Raises self from seat of

wheelchair every 15 minutes

Increases mobility

a) Performs range-of-motion

exercises

b) Adheres to turning

schedule

c) Advances sitting time as

tolerated

Sensory and cognitive ability improved

a) Demonstrates improved

level of consciousness

b) Remembers to inspect

potential pressure ulcer areas every morning and evening

Demonstrates improved tissue perfusion

a) Exercises to increase

circulation

b) Elevates body parts

susceptible to edema

Attains and maintains adequate nutritional status

a) Verbalizes the

importance of protein and vitamin C in diet

b) Eats diet high in

protein and vitamin C

c) Maintains hemoglobin,

electrolyte, albumin, transfer-rin, and creatinine levels at acceptable levels

Avoids friction and shear

a) Avoids semireclining

position

b) Uses sheepskin pad and

heel protectors when appropriate

c) Lifts body instead of

sliding across surfaces

Maintains clean, dry skin

a) Avoids prolonged contact

with wet or soiled surfaces

b) Keeps skin clean and dry

c) Uses lotion to keep skin

lubricated

Experiences healing of pressure ulcer

a) Avoids pressure on area

b) Improves nutritional

status

c) Participates in

therapeutic regimen

d) Demonstrates behaviors

to prevent new pressure ulcers

e) States early indicators

of pressure ulcer development

Related Topics