Chapter: Psychiatric Mental Health Nursing : Foundations of Psychiatric Mental Health Nursing

Mental Illness in the 21st Century

MENTAL ILLNESS IN THE 21ST CENTURY

The National Institute of

Mental Health (NIMH, 2008) estimates that more than 26% of Americans aged 18

years and older have a diagnosable mental disorder— approximately 57.7 million

persons each year. Further-more, mental illness or serious emotional

disturbances impair daily activities for an estimated 15 million adults and 4

million children and adolescents. For example, attention deficit hyperactivity

disorder affects 3% to 5% of school-aged children. More than 10 million

children younger than 7 years grow up in homes where at least one parent

suffers from significant mental illness or sub-stance abuse, a situation that

hinders the readiness of these children to start school. The economic burden of

mental illness in the United States, including both health-care costs and lost

productivity, exceeds the economic burden caused by all kinds of cancer. Mental

disorders are the leading cause of disability in the United States and Canada for

persons 15 to 44 years of age. Yet only one in four adults and one in five

children and adolescents requiring mental health services get the care they

need.

Some believe that

deinstitutionalization has had nega-tive as well as positive effects. Although

deinstitutionaliza-tion reduced the number of public hospital beds by 80%, the

number of admissions to those beds correspondingly increased by 90%. Such

findings have led to the term revolving

door effect. Although people with severe and per-sistent mental illness

have shorter hospital stays, they are admitted to hospitals more frequently.

The continuous flow of clients being admitted and discharged quickly overwhelms

general hospital psychiatric units. In some cities, emergency department visits

for acutely disturbed persons have increased by 400 to 500%.

Shorter hospital stays

further complicate frequent, repeated hospital admissions. People with severe

and persis-tent mental illness may show signs of improvement in a few days but

are not stabilized. Thus, they are discharged into the community without being

able to cope with community living. The result frequently is decompensation and

rehospi-talization. In addition, many people have a dual problem of both severe

mental illness and substance abuse. Use of alco-hol and drugs exacerbates

symptoms of mental illness, again making rehospitalization more likely.

Substance abuse issues cannot be dealt with in the 3 to 5 days typical for

admissions in the current managed care environment.

Homelessness is a major

problem in the United States today. One third of adult homeless persons are

estimated to have a serious mental illness and more than one half also have

sub-stance abuse problems. The segment of the homeless popula-tion considered

to be chronically homeless numbers 200,000, and 85% of this group has a

psychiatric illness or a substance abuse problem. Those who are homeless and

mentally ill are found in parks, airport and bus terminals, alleys and

stairwells, jails, and other public places. Some use shelters, halfway houses,

or board-and-care rooms; others rent cheap hotel rooms when they can afford it.

Homelessness worsens psychi-atric problems for many people with mental illness

who end up on the streets, contributing to a vicious cycle. The Treatment

Advocacy Center (2008) reports that rates of mental illness, par-ticularly

major depression, bipolar disorder, and substance abuse, are increasing among

the homeless population.

Many of the problems of the

homeless mentally ill, as well as of those who pass through the revolving door

of psy-chiatric care, stem from the lack of adequate community resources. Money

saved by states when state hospitals were closed has not been transferred to

community programs and support. Inpatient psychiatric treatment still accounts

for most of the spending for mental health in the United States, so community

mental health has never been given the financial base it needs to be effective.

In addition, men-tal health services provided in the community must be

indi-vidualized, available, and culturally relevant to be effective.

In 1993, the federal

government created and funded Access to Community Care and Effective Services

and Support (ACCESS) to begin to address the needs of people with mental

illness who were homeless either all or part of the time. The goals of ACCESS

were to improve access to comprehensive services across a continuum of care,

reduce duplication and cost of services, and improve the efficiency of services.

Programs such as these provide services to people who otherwise would not

receive them and have proved successful in treating psychiatric illness and in

decreasing homelessness.

Objectives for the Future

Unfortunately, only one in

four affected adults and one in five children and adolescents receive treatment

(Depart-ment of Health and Human Services [DHHS], 2008).

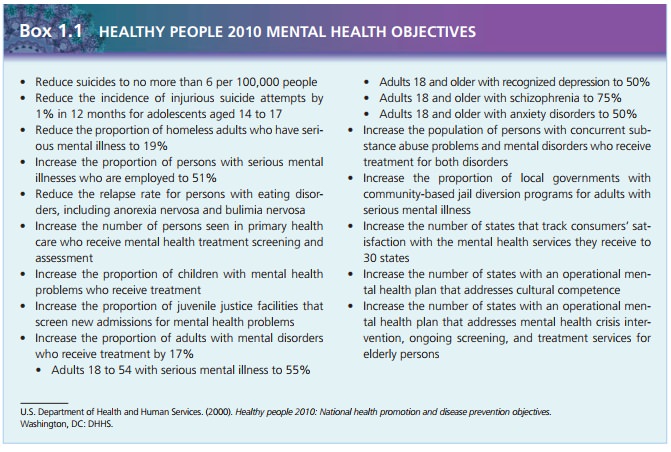

Statistics like these

underlie the Healthy People 2010 objec-tives for mental health proposed by the

U.S. DHHS. These objectives, originally developed as Healthy People 2000, were

revised in January 2000 to increase the number of people who are identified,

diagnosed, treated, and helped to live healthier lives. The objectives also

strive to decrease rates of suicide and homelessness, to increase employment

among those with serious mental illness, and to provide more services both for

juveniles and for adults who are incarcerated and have mental health problems.

At this time, work has begun on Healthy People 2020 goals, which will be

released in January 2010.![]()

![]()

Community-Based Care

After deinstitutionalization,

the 2,000 community mental health centers that were supposed to be built by

1980 had not materialized. By 1990, only 1,300 programs provided various types

of psychosocial rehabilitation services. Per-sons with severe and persistent

mental illness were either ignored or underserved by community mental health

cen-ters. This meant that many people needing services were, and still are, in

the general population with their needs unmet. The Treatment Advocacy Center

(2008) reports that about one half of all persons with severe mental ill-ness

have received no treatment of any kind in the previ-ous 12 months. Persons with

minor or mild cases are more likely to receive treatment, whereas those with severe

and persistent mental illness are least likely to be treated.

Community support service

programs were developed to meet the needs of persons with mental illness

outside the walls of an institution. These programs focus on reha-bilitation,

vocational needs, education, and socialization as well as on management of

symptoms and medication. These services are funded by states (or counties) and

some private agencies. Therefore, the availability and quality of services vary

among different areas of the country. For example, rural areas may have limited

funds to provide mental health services and smaller numbers of people needing

them. Large metropolitan areas, although having larger budgets, also have

thousands of people in need of service; rarely is there enough money to provide

all the services needed by the population.

Unfortunately, the

community-based system did not accu-rately anticipate the extent of the needs

of people with severe and persistent mental illness. Many clients do not have

the skills needed to live independently in the community, and teaching these

skills is often time consuming and labor inten-sive, requiring a 1:1

staff-to-client ratio. In addition, the nature of some mental illnesses makes

learning these skills more difficult. For example, a client who is

hallucinating or “hearing voices” can have difficulty listening to or

compre-hending instructions. Other clients experience drastic shifts in mood,

being unable to get out of bed one day and then unable to concentrate or pay

attention a few days later.

Despite the flaws in the

system, community-based pro-grams have positive aspects that make them

preferable for treating many people with mental illness. Clients can remain in

their communities, maintain contact with family and friends, and enjoy personal

freedom that is not possi-ble in an institution. People in institutions often

lose moti-vation and hope as well as functional daily living skills, such as

shopping and cooking. Therefore, treatment in the community is a trend that

will continue.

Cost Containment and Managed Care

Health-care costs spiraled

upward throughout the 1970s and 1980s in the United States. Managed care is a concept designed to

purposely control the balance between the quality of care provided and the cost

of that care. In a man-aged care system, people receive care based on need

rather than on request. Those who work for the organization pro-viding the care

assess the need for care. Managed care began in the early 1970s in the form of

health maintenance organizations, which were successful in some areas with

healthier populations of people.

In the 1990s, a new form of

managed care, called utilization review

firms or managed care organizations,

was developed to control the expenditure of insurance funds by requiring

providers to seek approval before the delivery of care. Case management, or management ofcare on a case-by-case basis,

represented an effort to pro-vide necessary services while containing cost. The

client is assigned to a case manager, a person who coordinates all types of

care needed by the client. In theory, this approach is designed to decrease

fragmented care from a variety of sources, eliminate unneeded overlap of

services, provide care in the least restrictive environment, and decrease costs

for the insurers. In reality, expenditures are often reduced by withholding

services deemed unnecessary or substituting less expensive treatment

alternatives for more expensive care, such as hospital admission.

Psychiatric care is costly

because of the long-term nature of the disorders. A single hospital stay can

cost $20,000 to $30,000. Also, there are fewer objective measures of health or

illness. For example, when a per-son is suicidal, the clinician must rely on

the person’s report of suicidality; no laboratory tests or other diagnos-tic

studies can identify suicidal ideas. Mental health care is separated from

physical health care in terms of insur-ance coverage: There are often specific

dollar limits or permitted numbers of hospital days in a calendar year. When

private insurance limits are met, public funds through the state are used to

provide care. As states expe-rience economic difficulties, the availability of

state funds for mental health care decreases as well.

Mental health care is managed

through privately owned behavioral health-care firms that often provide the

servicesand manage their cost. Persons without private insurance must rely on

their counties of residence to provide funding through tax dollars. These

services and the money to fund them often lag far behind the need that exists.

In addition, many persons with mental illness do not seek care and in fact

avoid treatment. These persons are often homeless or in jail. Two of the

greatest challenges for the future are to provide effective treatment to all

who need it and to find the resources to pay for this care.

The Health Care Finance

Administration administers two insurance programs: Medicare and Medicaid.

Medicare cov-ers people 65 years and older, people with permanent kidney

failure, and people with certain disabilities. Medicaid is jointly funded by

the federal and state governments and cov-ers low-income individuals and

families. Medicaid varies depending on the state; each state determines

eligibility requirements, scope of services, and rate of payment for ser-vices.

Medicaid covers people receiving either SSI or SSDI until they reach 65 years

of age, although people receiving SSDI are not eligible for 24 months. SSI recipients,

however, are eligible immediately. Unfortunately, not all people who are

disabled apply for disability benefits, and not all people who apply are

approved. Thus, many people with severe and persistent mental illness have no

benefits at all.

Another funding issue is

mental health parity, or equal-ity, in insurance coverage provided for both

physical and mental illnesses. In the past, insurers had spending caps for

mental illness and substance abuse treatment. Some policies placed an annual

dollar limitation for treatment, whereas others limited the number of days that

would be covered annually or in the insured person’s lifetime (of the policy).

In 1996, Congress passed the Mental Health Parity Act, which eliminated annual

and lifetime dollar amounts for mental health care for companies with more than

50 employees. However, substance abuse was not covered by this law, and

companies could still limit the number of days in the hospital or the number of

clinic visits per year. Thus, parity did not really exist. Insurance is

governed by the laws of each state, so some states have full parity, while

others have “limited” parity for mental health coverage— and some states have

no parity laws on the books (National Alliance for the Mentally Ill [NAMI], 2007).

Cultural Considerations

The U.S. Census Bureau (2000)

estimates that 62% of the population has European origins. This number is

expected to continue to decrease as more U.S. residents trace their ancestry to

African, Asian, Arab, or Hispanic origins. Nurses must be prepared to care for

this culturally diverse popula-tion, which includes being aware of cultural

differences that influence mental health and the treatment of mental illness.

Diversity is not limited to culture; the structure of fami-lies has changed as well. With a divorce rate of 50% in the United States, single parents head many families and manyblended families are created when divorced persons remarry. Twenty-five percent of households consist of a single person (U.S. Census Bureau, 2000), and many people live together without being married. Gay men and lesbians form partner-ships and sometimes adopt children. The face of the family in the United States is varied, providing a challenge to nurses to provide sensitive, competent care.

![]()

![]()

Related Topics