Chapter: Psychiatric Mental Health Nursing : Abuse and Violence

Intimate Partner Violence

INTIMATE PARTNER VIOLENCE

Intimate partner violence is the mistreatment or misuse

of one person by another in the

context of an emotionally intimate relationship. The relationship may be

spousal, between partners, boyfriend, girlfriend, or an estranged relationship.

The abuse can be emotional or psychological, physical, sex-ual, or a

combination (which is common). Psychological

abuse (emotional abuse) includes

name-calling, belittling, screaming,

yelling, destroying property, and making threats as well as subtler forms, such

as refusing to speak to or ignoring the victim. Physical abuse ranges from shoving and pushing to severe battering

and choking and may involve broken limbs and ribs, internal bleeding, brain

dam-age, and even homicide. Sexual abuse includes assaults dur-ing sexual

relations such as biting nipples, pulling hair, slapping and hitting, and rape

(discussed later).

From 90% to 95% of domestic violence victims are women, and one in

three women in the United States is esti-mated to have been beaten by a spouse

at least once. Each year, as many as 5.3 million women in the United States

experience a serious assault by a partner. Eight percent of U.S. homicides

involve one spouse killing another, and 3 of every 10 female homicide victims

are murdered by their spouse, ex-spouse, boyfriend, or ex-boyfriend. Of all

inti-mate partner homicides, 25% are male and 75% are female (Centers for

Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2008).

An estimated 324,000 women experience violence while pregnant.

Battering during pregnancy leads to adverse outcomes, such as miscarriage and

stillbirth, as well as to further physical and psychological problems for the

woman. The increase in violence often results from the partner’s jealousy,

possessiveness, insecurity, and lessened physical and emotional availability of

the pregnant woman (Bacchus, Mezey, & Bewley, 2006).

Domestic violence occurs in same-sex relationships with the same

statistical frequency as in heterosexual rela-tionships and affects 50,000

lesbian women and 500,000 gay men each year. Although same-sex battering

mirrors heterosexual battering in prevalence, its victims receive fewer

protections. Seven states define domestic violence in a way that excludes

same-sex victims. Twenty-one other states have sodomy laws that designate sodomy (anal intercourse) as a crime;

thus, same-sex victims must first confess to the crime of sodomy to prove a

domestic rela-tionship between partners. The same-sex batterer has an

additional weapon to use against the victim: the threat of revealing the

partner’s homosexuality to friends, family, employers, or the community.

Clinical Picture

Because abuse often is perpetrated by a husband against a wife,

that example is used in this section. These samepatterns are consistent,

however, between partners who are not married, between same-sex partners, and

with wives who abuse their husbands.

An abusive husband often believes his wife belongs to him (like

property) and becomes increasingly violent and abusive if she shows any sign of

independence, such as get-ting a job or threatening to leave. Typically, the

abuser has strong feelings of inadequacy and low self-esteem as well as poor

problem-solving and social skills. He is emotionally immature, needy,

irrationally jealous, and possessive. He may even be jealous of his wife’s

attention to their own chil-dren or may beat both his children and his wife. By

bullying and physically punishing the family, the abuser often expe-riences a

sense of power and control, a feeling that eludes him outside the home.

Therefore, the violent behavior often is rewarding and boosts his self-esteem.

Dependency is the trait most commonly found in abused wives who

stay with their husbands. Women often cite personal and financial dependency as

reasons why they find leaving an abusive relationship extremely diffi-cult.

Regardless of the victim’s talents or abilities, she per-ceives herself as

unable to function without her husband. She too often suffers from low

self-esteem and defines her success as a person by her ability to remain loyal

to her marriage and “make it work.” Some women internalize the criticism they

receive and mistakenly believe they are to blame. Women also fear their abuser

will kill them if they try to leave. This fear is realistic, given that

national statistics show 65% of women murdered by spouses or boyfriends were

attempting to leave or had left the rela-tionships (Bureau of Justice

Statistics, 2007).

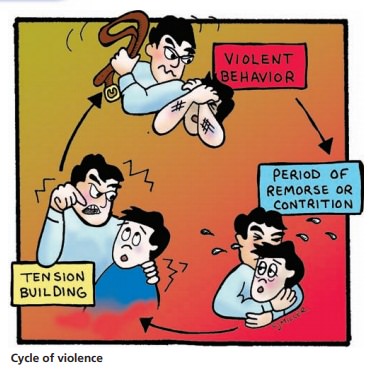

Cycle of Abuse and Violence

The cycle of violence or

abuse is another reason often cited for why women have difficulty leaving

abusive rela-tionships. A typical pattern exists: Usually, the initial epi-sode

of battering or violence is followed by a period of the abuser expressing

regret, apologizing, and promising it will never happen again. He professes his

love for his wife and may even engage in romantic behavior (e.g., buying gifts

and flowers). This period of contrition or remorse sometimes is called the honeymoon period. The woman naturally

wants to believe her husband and hopes the vio-lence was an isolated incident.

After this honeymoon period, the tension-building phase begins; there may be

arguments, stony silence, or complaints from the husband. The tension ends in

another violent episode after which the abuser once again feels regret and

remorse and prom-ises to change. This cycle continually repeats itself. Each

time, the victim keeps hoping the violence will stop.

Initially, the honeymoon period may last weeks or even months,

causing the woman to believe that the relationship has improved and her

husband’s behavior has changed. Over time, however, the violent episodes are

more frequent, the period of remorse disappears altogether, and the level of

violence and severity of injuries worsen. Eventually, the violence is

routine—several times a week or even daily.

While the cycle of violence is the most common pattern of intimate

partner violence, it does not apply to all situations. Many survivors report

only one or two elements of the cycle. For example, there may be only periodic

episodes of violent behavior with no subsequent honeymoon period, or no observable

period of increasing tension.

Assessment

Because most abused women do not seek direct help for the problem,

nurses must help identify abused women in vari-ous settings. Nurses may

encounter abused women in emer-gency rooms, clinics, or pediatricians’ offices.

Some victims may be seeking treatment for other medical conditions not directly

related to the abuse or for pregnancy. Identifying abused women who need

assistance is a top priority of the Department of Health and Human Services.

The generalist nurse is not expected to deal with this complicated problem

alone. He or she can, however, make referrals and contact appropriate

health-care professionals experienced in work-ing with abused women. Above all,

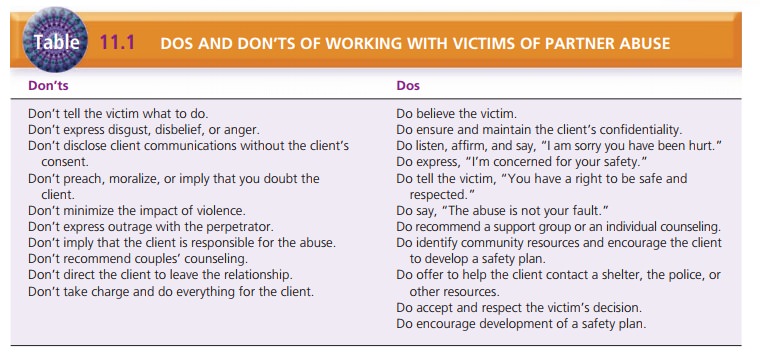

the nurse can offer caring and support throughout. Table 11.1 summarizes

techniques for working with victims of partner violence.

Many hospitals, clinics, and doctors’ offices ask women about

safety issues as part of all health histories or intake interviews. Because

this issue is delicate and sensitive and many abused women are afraid or

embarrassed to admit the problem, nurses must be skilled in asking appropriate

questions about abuse. The nurse should ask questions in the other two

categories if abuse is pres-ent. He or she should ask these questions when the

woman is alone; the nurse can paraphrase or edit the questions as needed for

any given situation.

Treatment and Intervention

Every state in the United States allows police to make arrests in

cases of domestic violence; more than half the states have laws requiring

police to make arrests for at least some domestic violence crimes. Sometimes

after police have been called to the scene, the abuser is allowed to remain at

home after talking with police and calming down. If an arrest is made,

sometimes the abuser is held only for a few hours or overnight. Often the

abuser retaliates upon release; hence, women have a legitimate fear of calling

the police. Studies have shown that arresting the batterer may reduce

short-term violence but may increase long-term violence.

A woman can obtain a restraining

order (protection order) from her county of residence that legally

prohibits the abuser from approaching or contacting her. Never-theless, a

restraining order provides only limited protec-tion. The abuser may decide to

violate the order and severely injure or kill the woman before police can

inter-vene. Civil orders of protection are more effective in preventing future

violence when linked with other inter-ventions such as advocacy counseling,

shelter, or talkingwith their health-care provider (McCloskey et al., 2006).

Women who left their abusive relationships were more likely to be successful if

they were younger aged, had an abuse-related physician visit, had attempted to

leavepreviously, and had a civil order of protection (Koepsell, Kernic, &

Holt 2006).

Even after a victim of battering has “ended” the rela-tionship,

problems may continue. Stalking, or

repeated and persistent attempts to impose unwanted communica-tion or contact

on another person, is a problem. Stalkers usually are “would-be lovers,”

pursuing relationships that have ended or never even existed. Twenty-five

percent of women and 10% of men can expect to be victims of ongo-ing unwanted

pursuit. Nearly 1 in 22 adults, almost 10 million people, have been stalked in

the United States, with 80% of the victims being female (Basile, Swahn, Chen,

& Saltzman, 2006).

Battered women’s shelters can provide temporary housing and food for

abused women and their children when they decide to leave the abusive

relationship. In many cit-ies, however, shelters are crowded; some have waiting

lists, and the relief they provide is temporary. The woman leav-ing an abusive

relationship may have no financial support and limited job skills or

experience. Often she has depen-dent children. These barriers are difficult to

overcome, and public or private assistance is limited.

In addition to the many physical injuries that abused women may

experience, there are emotional and psycho-logical consequences. Individual

psychotherapy or coun-seling, group therapy, or support and self-help groups

can help abused women deal with their trauma and begin to build new, healthier

relationships.

Related Topics