Chapter: XML and Web Services : Applied XML : Implementing XML in E-Business

ebXML

ebXML

One of the major projects targeted at solving some

of these e-business problems for small, medium, and large organizations is the

e-business XML (ebXML) project, a joint project from UN/CEFACT and OASIS. EbXML

is aimed squarely at making e-business transactions accessible to all businesses, including the smallest

of business organizations.

EbXML was created in 1999 as a joint partnership by UN/CEFACT and OASIS

in order to replace or augment existing EDI standards. The group saw the main

challenge as being able to deliver the same value large organizations realized

in the EDI specification to small- and medium-sized enterprises (SME). The

ebXML group saw its main goal as producing an XML-based standard that would

accelerate e-business deployment, reduce cost, be easy to support, and support

worldwide business needs. It is for this reason that many say that ebXML

“supports anyone, anywhere to do business with anyone else over the Internet.”

The specification intends for companies of all sizes to be able to dynami-cally

locate each other via the Internet in order to conduct business through XML-based

electronic messages.

The ebXML effort has been developed in an open environment, and as a

result participa-tion is free and open to anyone. The specification was also

designed to be complimentary with existing standards and technical

specifications such as UN/EDIFACT, ASC X12, and others. The goal was not to

reinvent the wheel in e-business but rather to apply what was learned there to

SMEs. The final result is a “plug-and-play” architecture that allows modular

and incremental use of ebXML technologies by those interested. The end intent

is that vendors will build applications that support these open standards that

are afford-able, easily developed, and available even for the smallest of

organizations. The promise of ebXML is the ability to fulfill all business

communication needs, but as we all know, ambition and end result sometimes do

not meet.

The ebXML framework was developed as part of an intense, global effort

that lasted only 18 months. As part of this process, UN/CEFACT was involved

because it is one of only four international bodies that can enact legally

binding standards. UN/CEFACT has pre-viously lent its weight to the development

and standardization of the global EDI format known as UN/EDIFACT. The final

specification was delivered in May of 2001 in Vienna, Austria. At this event, a

proof of concept demonstration was shown in which over two dozen companies and

organizations demonstrated their implementations of ebXML.

The ebXML specification is comprised of three main infrastructure

components and sev-eral other supporting technologies focused on such issues as

document creation and busi-ness process definition. These architecture

components are designed so they may be independently and modularly implemented.

The ebXML infrastructure components include the following:

Collaborative Protocol Profile

(CPP)

Core components

Registry and repository

Messaging

Business process modeling

Needless to say, ebXML utilizes XML for the definition of all messages,

process models, and supporting content. However, ebXML may transport any type

of data, such as binary content or EDI transactions. It is notable that ebXML

expresses trading partner agree-ments and business service interfaces in XML as

well. The only major non-XML

component of the architecture is the common business process models,

which utilize established modeling standards such as the Unified Modeling

Language (UML), the results of which are stored in a global registry.

It should be noted that there are not one but rather two ebXML architectures.

One of these architectures describes the software components of the technical

infrastructure and is known as a product

architecture. The other architecture is focused on systems analysis and

development and is known as a process

architecture. The actualization of these dif-ferent architecture models is

realized in the Business Operational View (BOV) and Functional Service View

(FSV), which are described later in this chapter.

Also, the ebXML architecture has been constructed in a way that its

various components and sections, as described earlier, can be used

independently and without dependency. This loosely related nature of the

systems allows users to pick and choose those aspects of ebXML that are best

suited to their operations without unnecessary baggage in sup-porting

components they are not interested in.

Overview of ebXML Process

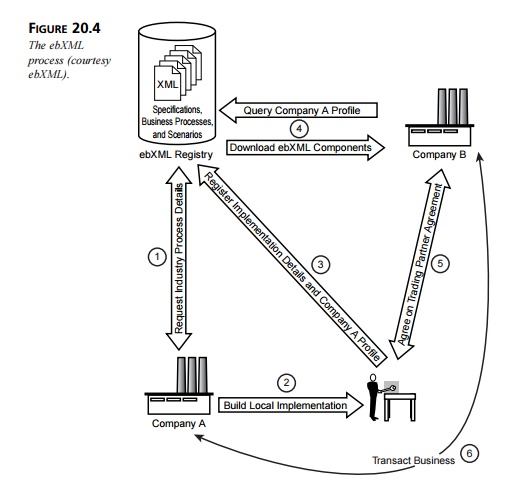

The process followed in the ebXML model can be simply described as two

companies— Company A and Company B—that desire to conduct business in a trading

partner relationship. First, the originating trading partner, Company A, looks

up industry specifi-cations and business processes and builds a local

implementation. The company then cre-ates a profile for its business, known as

the Collaborative Protocol Profile (CPP), and registers it with the registry.

Company A might wish to contribute new business processes to the registry or

simply reference available ones. The CPP contains all the information necessary

for potential trading partners to determine which business roles Company A is

interested in, and which technologies and protocols it can engage in for these

various roles.

After Company A registers itself in the registry, a prospective trading

partner, Company B, can search the repository for Company A’s CPP and check to

make sure that its profile is compatible with Company B’s requirements. The

next step is that a Collaboration Protocol Agreement (CPA) is automatically

negotiated between parties based on the con-formance of the CPPs as well as

associated protocols and other standards and recommen-dations. The final result

is that the two organizations can now conduct business. The transactions are

encoded in business messages that are encapsulated in ebXML message envelopes

and conducted according to industry needs. The ebXML process is illustrated in

Figure 20.4.

Collaborative Protocol Profile

The Collaboration Protocol Profile (CPP) describes a company’s

message-exchange capabilities, business processes, and business collaborations

in a standardized and portable manner. The business processes that are

described indicate how trading partners are to interact with the company. A

business collaboration describes both “ends” of a B2B transaction, meaning that

in a typical buyer-seller scenario, the CPP describes the selling process and

semantics of the seller as well as the buying process and semantics of the

buyer. The resulting CPP is stored with a registry to later be located and

searched.

The Collaboration Protocol Agreement (CPA) is an addition to this model

that describes the exact requirements and mechanisms for the transactions that

two companies perform with each other. The CPA is formed by combining the CPPs

of the two organizations and can be manually formed or automatically generated depending

on the commerce transac-tion scenario. The CPA therefore becomes a binding

contract that describes the terms and conditions for individual collaborations.

The CPA is the actual implementation of a CPP by virtue of agreement on given

terms. For example, if a CPP indicates that some prop-erty can be utilized in a

transaction, the CPA will state that the given property will be used in a given commerce exchange.

The CPP specifies such properties as the contact information of an

organization, supported network and file transport protocols, specific network

addresses, security implementations, and business process specifications.

Core Components

An important part of the ebXML architecture is the specification of a

set of ebXML schemas that contain formats for different types of shared

business data such as dates, monetary amounts, tax formats, account owners,

exchange contracts, and other specifica-tions. These schemas are known as core components and are shared across

all industries and user communities. The core components are meant to be the

basic “atoms” of infor-mation used in business messages and are also known as common business objects in other

e-business specifications. The schemas also provide a means to enable

extensibility so that different types of information in different industries,

geographies, or individual organizations can represent the same information in

different ways.

In addition, ebXML describes a “core library” that defines a standard

set of parts that will, in turn, be used by other ebXML elements. This library

can contain such items as core processes that are referenced by more specific

business processes.

Registry and Repository

The ebXML registry is a central storage facility that stores the data

required for ebXML to interact with organizations and their profiles. The

registry stores a variety of business-related information, including the core

components, CPPs, business process and informa-tion meta models, and related

documents or fragments, including Web Services documents, Java files, and even

multimedia documents. The registry is the place where ebXML-participating

businesses go before and during the conducting of electronic busi-ness

transactions. Basically, when a business wants to start an ebXML relationship

with another business, it queries a registry in order to locate a suitable

partner and to find information about requirements for dealing with that

partner.

The registry contains a set of query capabilities that allows users to

search for relevant documents and potential business partners. Technologies

such as the Java APIs for XML Registries (JAXR) can be used to query ebXML

registries. In addition, the ebXML reg-istry has a relationship with the more

Web Services–centric Universal Description, Discovery and Integration (UDDI)

registry.

UDDI was developed as a joint project co-sponsored by IBM, Microsoft,

and Ariba and announced in September 2000. The main difference between the

ebXML registry and UDDI’s is that the ebXML registry is a local container for

actual business information itself that can be of any type of content,

including CPP, schemas, commonly used XML components, as well as Web Services,

whereas the UDDI registry is mainly meant to be a global source of Web

Services–related content. The UDDI registry system contains three types of

information: white, yellow, and green pages. White pages store information

about companies’ organizational profiles, including their names and key

services. Yellow pages categorize these organizations by industry standard codes

or by physical geograph-ical location. Green pages provide a mechanism for

companies to store their actual ser-vices interfaces that allow them to

interface with other organizations. It is quite feasible, however, for business

partners to first search UDDI registries that could result in refer-ences to a

CPP stored in an ebXML registry. Therefore, this becomes a two-step process,

leveraging the benefits of both systems.

Originally, the ebXML registry was going to be a fully distributed,

networked set of interacting registries that would provide transparent

interaction to any ebXML-compliant registry through interfacing with a single

source, but time constraints lead to the specifi-cation of just a single

registry. Instead, the group now leverages its partnership with UDDI, as

mentioned earlier.

In many cases, the terms registry

and repository are used

interchangeably, but in truth, the two perform different functions. The

registry provides the interface and access mech-anism, information model, and

reference system implementation, whereas the repository provides the actual,

physical information store.

Messaging

Messages specified by ebXML are sent between partners by means of the

messaging architecture, which provides an “envelope” encapsulating a message

with all necessary transmission semantics, including asynchronous or

synchronous communications modes, transaction control, security, and

reliability settings. The messaging service provides the means for the system

to exchange a “payload,” which may or may not be an actual ebXML business

document. In addition to the enveloping and transmission capabilities, an ebXML

message can specify routing instructions to ensure that a given party receives

the document. EbXML messages utilize SOAP as the actual mechanism for message

passing and extend the SOAP protocol via additional functionality to support

attach-ments, security, and reliable delivery. The actual transport protocol,

such as HTTP, SMTP, or FTP, is left to the user to implement.

Business Process and Information Modeling

As with all e-business systems, most of the intelligence in a system is

stored not in the actual XML-encoded messages but in the business processes

that surround the docu-ments. Business process information includes transaction

requirements, workflow and document processing, collaboration, and data

encapsulation, among other related things. These business process documents

describe how a business functions internally and how other organizations can

appropriately interface with the company. As systems move from being human

based to being machine automated, the appropriate electronic rendition of these

processes is of utmost importance.

Business processes are formally described in ebXML by the Business

Process Speci-fication Schema (BPSS) and may also be modeled in UML. The BPSS

describes all the activities that a business is interested in engaging in with

its partners.

Using an XML DTD, BPSS provides a definition of an XML document that

describes the way an organization does business. The CPA and CPP deal

specifically with the tech-nical and integration needs and aspects of a

business but don’t specifically deal with the business processes and workflow

inherent in a company. Rather, the BPSS specifically handles modeling around

the roles, specification of business document usage, general processes,

workflow and document flow, security and legal aspects, transactions,

acknowledgments, and overall status. The BPSS can then be used to create

applications that automatically configure the system based on the specific

business details of a trading partner.

In addition, users can use the UN/CEFACT Modeling Methodology (UMM),

which uti-lizes UML, as a means to model ebXML business processes. UMM is an

implementation of UML that specifically deals with methods for performing

business and information modeling in the context of an e-business system. The

model prescribes the specific items and their relationships that are to be

produced from modeling analysis. The BPSS itself is just a subset of the UMM

information model. To simplify the process, ebXML has produced simple

“worksheets” that can enable nontechnical users to create information necessary

for BPSS without performing full UMM modeling. These business process analysis

worksheets and guidelines assist nontechnical analysts with the process of

gath-ering the required data to describe a business process. In addition, ebXML

has also pro-duce a predefined catalog of common business processes that can be

reused by more specific BPSS definitions. The group has produced a set of

e-commerce patterns that are examples of common business patterns, a

methodology for discovering core components in preexisting business documents

or new processes, a set of standard naming conven-tions based on ISO 11179, and

catalogs of core components and context drivers to assist in helping users to

extend and build definitions of business messages.

The business process specification DTD declaration can be found in

Listing 20.1.

LISTING 20.1 ProcessSpecification DTD Declaration (Courtesy of ebXML.org)

<!ELEMENT ProcessSpecification

(Documentation*,

(Include*

| DocumentSpecification* |

ProcessSpecification* | Package |

BinaryCollaboration | BusinessTransaction | MultiPartyCollaboration)*)>

<!ATTLIST ProcessSpecification

name ID #REQUIRED

version CDATA #REQUIRED

uuid CDATA #REQUIRED >

As you can see, the ebXML process specification contains a root element

called ProcessSpecification, which may contain references to other process or document specifications or other information.

Each process specification has a globally unique identifier called “uuid” as well as a name and version

that is specific to the model being represented. Within the process

specification is a defined set of collaborations that are either MultiPartyCollaboration elements or BinaryCollaboration elements. These collaborations

play roles for the transacting business parties. Listing 20.2 shows an excerpt

of a sample package of collaborations.

LISTING 20.2 A Package of Collaborations

(Courtesy of ebXML.org)

<Package name=”Ordering”>

<!— First the overall MultiParty Collaboration

—>

<MultiPartyCollaboration name=”DropShip”>

<BusinessPartnerRole

name=”Customer”>

<Performs

authorizedRole=”requestor”/>

<Performs

authorizedRole=”buyer”/>

<Transition

fromBusinessState=”Catalog

Request”

toBusinessState=”Create

Order”/>

</BusinessPartnerRole>

<BusinessPartnerRole

name=”Retailer”> <Performs authorizedRole=”provider”/>

<Performs

authorizedRole=”seller”/> <Performs authorizedRole=”Creditor”/>

<Performs

authorizedRole=”buyer”/> <Performs authorizedRole=”Payee”/>

...

<BinaryCollaboration

name=”Request Catalog”>

<AuthorizedRole

name=”requestor”/> <AuthorizedRole name=”provider”/>

<BusinessTransactionActivity name=”Catalog Request” businessTransaction=”Catalog Request”

fromAuthorizedRole=”requestor” toAuthorizedRole=”provider”/>

</BinaryCollaboration>

Business Messages

The final element of ebXML architecture is the actual business messages

themselves. These documents contain the business-level information that is sent

as part of the e-busi-ness communication. The business message is wrapped in a

number of layers as per the previous description. Business messages are wrapped

within ebXML message envelopes, which in turn are wrapped in SOAP messages that

are communicated via HTTP, SMTP, FTP, or some other protocol. The business

message is simply considered to be a “pay-load” for the ebXML system.

Proof of Concept Demonstration

In order to verify that the concepts within the ebXML specification meet

real-world requirements, a simultaneous effort to produce a “proof of concept”

has been initiated by the group. The workgroup has demonstrated its progress at

each quarterly ebXML meet-ing and has shown how the various components are

integrated. Feedback is given to each ebXML working group on problems,

challenges, and features discovered in the imple-mentation. Resulting standards

then reflect the results of the Proof of Concept team. The end result is to

create a specification that is real-world tested (to some degree) and meets the

needs of facilitating the implementation of cost effective e-business systems

for SMEs. At the last meeting of the working group in May 2001, more than two

dozen ven-dors participated in the Proof of Concept demonstration—and many of

these participants are software vendors who no doubt will be releasing products

based on ebXML.

More on ebXML Architecture

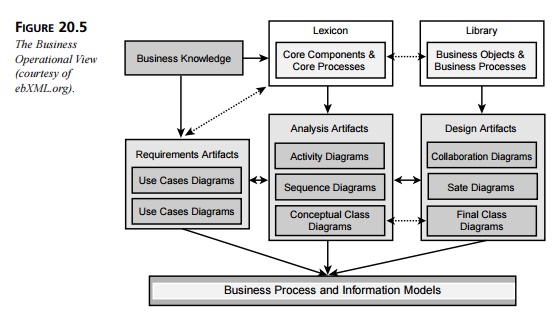

As mentioned earlier, there are really two different architectural views

of ebXML. We have spent much time covering the technical architecture of ebXML

but have not really spent much time with the conceptual thinking behind the

initiative. It is important to realize that the teams responsible for the

architecture approached the specification from a business workflow point of view.

This resulted in the creation and selection of business components and objects

that would be common to businesses across multiple industries, geographies, and

markets. These objects, such as location, party, and address, would be designed

not only to meet the specific needs of the various technical groups but also to

be reused in multiple, unexpected ways in the future. In this manner, ebXML

could be a constantly updated specification that unites cross-industry

e-business needs with a stan-dard technical definition.

The ebXML architectural model is a two-part conceptual model whose

origin is in the OpenEDI group of UN/CEFACT. The first part of this model is

the Business Operational View (BOV), which deals with the semantics of

e-business data exchanges. This view of the model deals with the various

operational requirements, agreements, and business obligations and requirements

for an e-business exchange that applies to ebXML trading partners. Figure 20.5

illustrates the BOV.

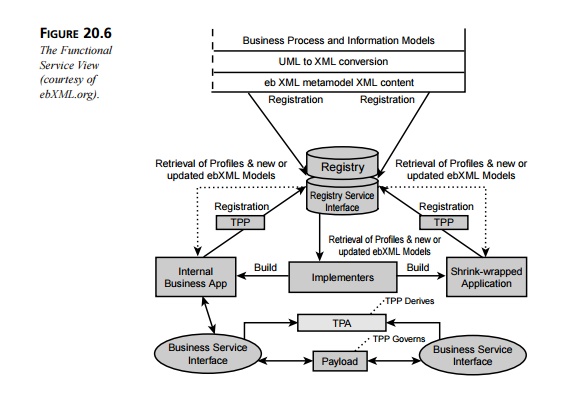

The second part of the model is the Functional Service View (FSV), which

deals more with the various deployment services and needs of ebXML. It deals

with the stages in which ebXML systems

are developed and deployed. The execution of the FSV consists of implementation,

discovery and deployment, and runtime phases. The implementation phase is

concerned with developing and creating ebXML-compliant systems and

infra-structures. The discovery and deployment phase deals with the various

aspects of discov-ering ebXML resources that can be manually or automatically

configured for use in

an ebXML system. Finally, the runtime phase deals with the actual

execution and physical aspects of e-business exchange in a real-world ebXML

scenario between trading partners.

In addition to these phases, it is important to note that the FSV has a

specific focus on the information technology (IT) requirements for the

implementation of a successful ebXML system. These various IT aspects include

the following:

Capabilities for implementation,

discovery, deployment, and runtime scenarios

Data-transfer infrastructure

interfaces

User application interfaces

Protocols for interoperation of

XML vocabulary deployments from different organizations

The registry serves as the means for actually delivering the BOV and

FSV, because it provides a set of integral services for enabling the sharing of

information, business processes, and related e-business data between ebXML

trading partners. The FSV is shown below in Figure 20.6.

Future Development and Maintenance

As per the original stated objectives of the group, the ebXML effort was

officially closed at the May 2001 meeting of ebXML in Vienna, Austria. The

ongoing development and maintenance of the infrastructure of ebXML has

officially been handed to the OASIS group, whereas the document definition,

process discovery, and process definition com-ponents were moved to a group

operating under the auspices of UN/CEFACT. In order to make sure that these two

groups stay in sync, a formal coordinating committee was formed with frequent

exchanges of progress.

Participation in ebXML is very high at the moment and consists of almost

every large software vendor and XML-consuming organization currently in the

market. Many associ-ations, government standards bodies, and other groups are

also members or otherwise affiliated with ebXML. Backers include a large number

of high-tech, manufacturing, logistics, finance, and other companies of many

different industries. Many standards groups are also working with ebXML, including

the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), W3C, and RosettaNet.

Related Topics