Chapter: XML and Web Services : Applied XML : Implementing XML in E-Business

What Is the Supply Chain?

What Is the Supply Chain?

Before we can spend time talking about how XML facilitates commerce of

all types, we first need to identify the ecosystem about which we are speaking.

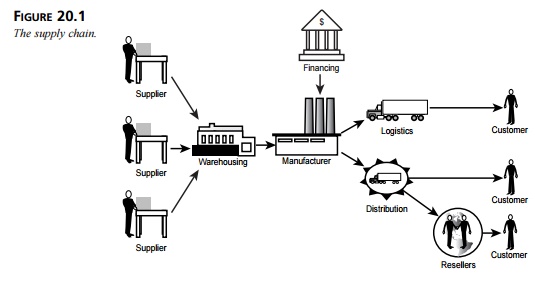

Commercial activity occurs within a well-defined system known as the supply chain, which consists of

partic-ipants that are interrelated in much the same way that different species

are related in a food chain. The supply chain, in effect, is comprised of the

interactions between parties that are required to produce products or services

and deliver them to customers. Figure 20.1 illustrates a supply chain that may

be used for a manufacturing organization. For individual companies and

industries, various portions of the supply chain may exist that may not exist

for other companies and industries.

The supply chain has evolved to become a focal point for automation and

electronically enabled processes. Because so many parties are involved in the

process of getting a prod-uct from a company to its customers, optimizing the

efficiency, lowering the cost, and increasing the return on investment (ROI)

for each of the portions of the supply chain is a major goal of most supply

chain management (SCM) techniques and technologies. SCM preceded the

development of the Internet and XML by many years—and in some cases decades. As

such, supply chain management concepts are not tied directly to

Internet-centric modes of thought. In fact, the classical definition of SCM (as

detailed on http://www.stanford.edu/~jlmayer/Article-Webpage.htm) is a “set of approaches utilized to efficiently integrate suppliers and clients (comprised of

stores, retailers, wholesalers, warehouses, and manufacturers) so merchandise

is produced and distributed at the right quantities, to the right locations,

and at the right time, in order to minimize system-wide costs while satisfying

service level requests.”

The concept of the supply chain rapidly evolved shortly after the

beginning of World War II. Prior to then, manufacturing and supply processes

were mostly paper-based processes that linearly connected manufacturers,

warehouses, wholesalers, retailers, and consumers. Some manufacturing processes

were relatively straightforward, whereas others were hopelessly complex

nightmares involving up to two dozen tiers of interaction. Each of these layers

of interaction required people and paper trails. Compounding this problem, the

linear nature of these processes made communication between arbitrary points on

the network a time- and cost-intensive process. It was obvious that for the

economy to be mobilized from a Depression-era inefficient system to a highly

organized, efficient wartime manufacturing machine, vast changes needed to

occur.

Old-style, multitier, linear supply chains had obvious inefficiencies

that masked inven-tory, supply, and other production problems in independent

layers of operation. An effi-cient supply chain would have to simplify and

enable the flow of critical supply information between different points on the

chain. World War II introduced a concept known as operations research and management science that helped to provide

conceptual solutions to these problems. Originally, operations research was

targeted at moving mili-tary goods and material to war fronts from supply

factories at home. Obviously, effi-ciency was a primary concern.

Prior to the widespread use of computing and networking power to solve

these problems, an interim solution known as cross-docking became a predominant method for optimiz-ing

efficiency. This method involved the manufacturing of products from multiple

plants and shipping them to multiple distribution centers. These centers, in

turn, distributed the products to multiple retail and outlet stores. This

process reduced the dependency on warehousing and reduced the time in which

manufactured goods reached their end desti-nations. Cross-docking results in

the invention of a number of techniques and technolo-gies still in use today,

such as the stock keeping unit (SKU),

which provides a numerical identifier for produced goods. The use of the SKU in

combination with the newly devel-oped barcode helped to enable electronic

sorting and management of stock within a cross-docking facility.

This increasing automation of the portions of the supply chain allowed

suppliers and consumers to gain increasing levels of awareness of the

efficiencies in the supply chain process. Products could be tracked, via their

SKU, from the time they’re produced at numerous suppliers to the time they arrive

at end-user locations. This increase in automa-tion also allowed the chain to

become less linear in nature. With a unifying means for identifying and sorting

goods, multiple suppliers, distribution centers, and retail outlets could be

used to reach the customer. The use of computers also reduced the need for

paper to be the means for tracking these movements of goods and services.

Reducing supply costs has dramatic impact on the profitability of a

business. In particu-lar, supply chain efficiencies enable the following:

Improved product margins (the

profit per unit produced)

Increased manufacturing

throughput and productivity

Better return on assets (net

income after expenses)

Shorter time to market for

developed goods

Better customer and supply chain

relationships

The development of a supply chain is a fluid and constantly changing

process. Supply chains are established upon the production of new products and

services. Contracts are negotiated and put in place to arrange the supply of

parts and materials. Management forecasts of demand and customer orders drive

the creation of production plans. As parts are manufactured by various

suppliers, inventory is managed. Agreements are signed with various sales and

marketing channels, such as retail stores, to deliver these goods to the end

customers. As sales are made, these channels deliver their forecasts and actual

sales to help further streamline the product manufacturing and supply process.

These days, most products are complex in nature. Each finished product

is assembled from parts and materials, which in turn are made of parts and

materials, and so on, down to the most basic of parts and materials. Airplanes,

automobiles, computers, and even tennis shoes are composed of dozens to

millions of parts. Optimizing the supply chain to make sure that the right

parts arrive in the right quantities at the right time is of extreme

importance. The core unit of this aggregation of products into a final product

is known as a bill of materials

(BOM). The BOM identifies the constituent parts in a finished prod-uct. Any

delays, production difficulties, or quality issues in constituent parts will

delay production of the whole product.

Nowadays, the supply chain is more of a “web.” Each manufacturer of

finished goods has relationships with dozens or hundreds of suppliers, each of

which have relationships with dozens or hundreds of manufacturing customers.

These interrelationships have enabled the use of dynamic supply agreements that

allow companies to constantly be on the lookout for better relationships and

deals. The increasing globalization of business has resulted in suppliers

existing anywhere in the world, covering many different coun-tries, languages,

and time zones. This globalization has added challenges and pressures in the

effort to optimize supply chains.

The supply chain itself applies to two different ways of conducting

business:

Business to Consumer (B2C)

Business to Business (B2B)

Business to Consumer (B2C)

All products have to get to customers at one point or another. In some

cases, the con-sumers are actual individual consumers rather than business

entities. Individual cus-tomers are a well-defined group of buyers that have

long been the objects of marketing, advertising, and other targeted selling

activities. Many of the early developments on the Internet were focused at

helping businesses directly sell their goods to customers. This model of

selling directly to individual end users of goods is known as Business to Consumer (B2C) sales processes.

The promise of B2C commerce is that it eliminates the “middlemen” and

expenses of going through multiple distribution and sales channels before

reaching the end customer. Of course, with the greater direct connection to the

customer comes increased marketing, sales, and support costs that would

otherwise be borne by various other elements in the channel. The most

well-known B2C companies include Amazon.com, Buy.com, and other such

direct-to-customer companies that provide services such as online banking, travel,

online auctions, health information, and real estate.

Other than the increased complexity and potential cost in dealing with

customers on a direct basis using B2C (or dot-com),

a company implementing B2C techniques faces the danger of channel conflict, or disintermediation. This occurs when a

manufacturer or ser-vice provider bypasses a reseller or salesperson and starts

selling directly to the cus-tomer. This has been increasingly the case in such

commodity industries as travel, banking, and electronic goods. However,

disintermediation of the channel can seriously backfire, upsetting long-term

relationships with dealers, distributors, and retailers.

Business to Business (B2B)

The other main source of customers for a business is other businesses.

Transacting with other businesses as customers is a comparably much larger

market than selling directly to end users. The Business to Business (B2B)

market is estimated at over 10 times the size of comparable B2C markets.

However, selling to businesses involves many differences and complexities that

are not present in traditional B2C sales environments.

Related Topics