Chapter: The Massage Connection ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY : Integumentary System

Variation in Skin Color

Variation in Skin Color

BLOOD FLOW AND SKIN COLOR CHANGES

Because blood vessels to the skin are extensive and lo-cated close to the surface, alterations in blood flow can be visually observed as changes in skin color. Color changes are better observed in those persons with light-colored skin and may not be as distinct in those persons with dark-colored skin. You can experiment on yourself or your colleagues and observe these changes. The characteristic pink color or reddish tint of the skin is a result of the oxygenated hemoglobin in the red blood cells. When blood flow is reduced temporarily, the skin becomes pale. If pressure is applied to the skin, the blood in the vessels of the skin, stagnates. Oxygen in the hemoglobin is quickly used by the tissue in the area, and the hemoglobin becomes darker as a result of deoxyhemoglobin formation. When observed through the skin, this reaction gives a bluish hue, termed cyanosis. The bluish discoloration is more prominentin areas where the epithelium is thin, such as the lips, tongue, beneath the nails, and conjunctiva. Watch the color change when you obstruct blood flow by tying a string or rubber band around a finger.

When a person is exposed to a cold environment, the blood vessels to the skin constrict to conserve heat and the person appears pale. If the temperature is low, however, cell injury occurs in exposed areas such as the tip of the nose or ear. The metabolites lib-erated by the injured cells cause the smooth muscle of the of blood vessel walls to dilate, producing the typical redness seen after frostbite.

During exercise, blood vessels in the skin dilate to dissipate heat, while blood vessels in most other parts of the body constrict. This is in response to the hypo-thalamus, which monitors temperature changes. This reflex response overrides all other reflex responses that may be triggered in the blood vessels in the skin.

White Reaction

Draw a pointed object lightly over your skin and ob-serve what happens. The stroke line becomes pale— the white line. The mechanical stimulus causes the smooth muscle guarding blood flow through the cap-illaries, called the precapillary sphincter, to contract. As a result, blood drains out of the capillaries and small veins and the skin turns pale.

The Triple Response

Now, draw a pointed object more firmly across the skin and observe. The stroke line turns red in about 10 seconds. This is called the red reaction. In a few minutes, swelling (wheal) and diffuse redness (flare) occur around the stroke line. The red reaction is caused by dilation of capillaries as a result of the stroke pressure. The wheal is a result of the increase in permeability of the capillaries and movement of fluid into the interstitial tissue caused by the release of histamine from mast cells located in the region. The flare is a result of arteriolar dilation. Together, the three responses are known as the triple response and are part of the normal response to injury.

Reactive Hyperemia

Tie a piece of string (or you may use a rubber band) firmly around your finger. Leave it in place for one minute and then remove it and observe what hap-pens. The skin turns fiery red soon after the occlusion is removed. This is known as reactive hyperemia. When blood flow to an area is restricted, the arteri-oles in that area dilate as a result of the release of chemicals (products of metabolism) by the oxygen-deprived cells. When blood flow is no longer re-stricted, blood rushes into the dilated blood vessels.

Erythema

At times, the skin appears red after injury, inflamma-tion, or exposure to heat. This redness is a result of dilatation of capillaries in the dermis and is termed erythema.

PIGMENTATION OF SKIN BY CAROTENE

Carotene is an orange-yellow pigment that tends to accumulate in epidermal cells and the fat cells of the dermis. It is found in abundance in orange-colored vegetables, such as carrots and squash. Light-skinned individuals who eat a lot of these vegetables, can have an orange hue to their skin as a result of the accu-mulation of this pigment. In darker-skinned individ-uals, the hue does not show up as well. Carotene is an important pigment that can be converted to vitamin A, which plays a role in the growth and maintenance of epithelia and synthesis of light receptor pigments of the eye.

SUBCUTANEOUS LAYER, OR HYPODERMIS

The subcutaneous layer, although not actually part of the skin, is an important layer that lies deep to the dermis. It is largely composed of connective tissue, which is interwoven with the connective tissue of the dermis. This layer stabilizes the skin, connecting it to underlying structures, while allowing some indepen-dent movement. At the same time, the subcutaneous tissue separates the deep fascia that surrounds mus-cles and organs from the skin. Therefore, this layer is also known as the superficial fascia. The subcuta-neous layer has a deposit of adipose (fat) tissue and serves as an energy reservoir and insulator. The adi-pose tissue also protects the underlying structures by serving as shock absorbers. The distribution of fat in the subcutaneous layer changes in adulthood. In men, it tends to accumulate in the neck, arms, along the lower back, and buttocks; in women, it accumu-lates primarily in the breasts, buttocks, hips, and thighs.

ACCESSORY STRUCTURES

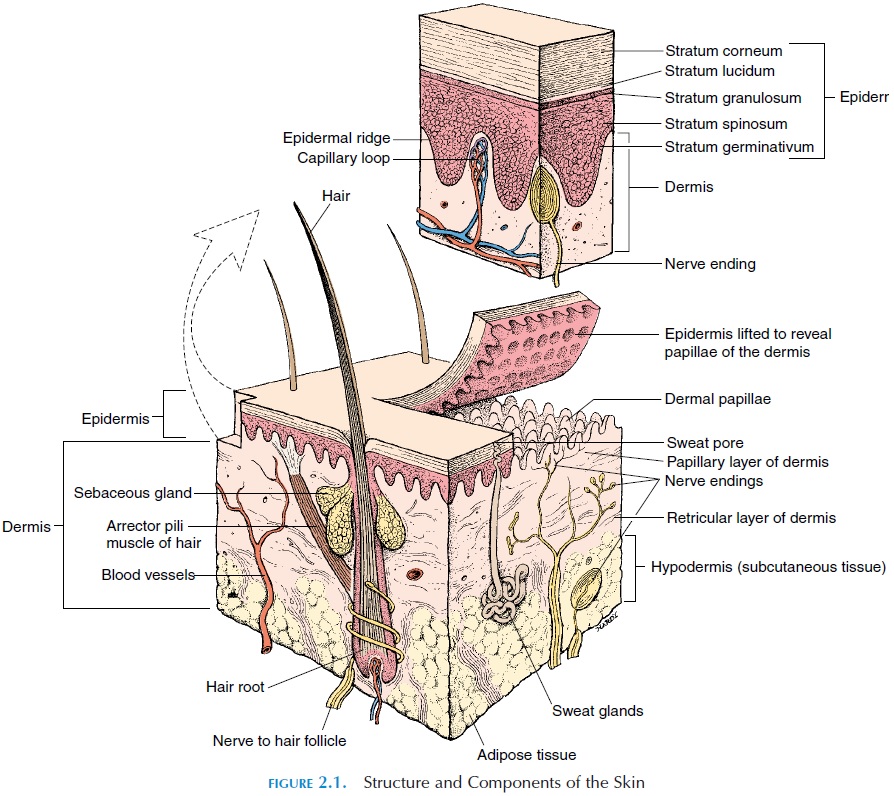

The accessory structures of the skin include the sweat glands, sebaceous glands, hair, and nails. They lie pri-marily in the dermis and project onto the surface through the epidermis.

Sweat Glands

The sweat glands, also known as sudoriferous or ec-crine glands (see Figure 2.1), are coiled tubularglands that are surrounded by a network of capillar-ies. Located in the dermis, they discharge secretions directly onto the surface of the skin or the hair folli-cles. There are two types of sweat glands: eccrine/merocrine and apocrine. Eccrine sweat glands arelocated over the entire body. There are approximately 2–5 million of these glands, with the forehead, palms, and soles having the highest number.

Sweat is 99% water. The remaining 1% consists of sodium chloride (responsible for sweat’s salty taste); other electrolytes; lactic acid; some nutrients, such as glucose and amino acid; and waste products, such as urea, uric acid, and ammonia. The main function of sweat is to cool the surface of the skin and, thereby,reduce the body temperature. The secretory activity of merocrine glands is controlled by the autonomic nerves and circulating hormones. When these glands are secreting at their maximal rate, such as during heavy exercise, up to a gallon of water may be lost in one hour.

The acidic pH of sweat, to some extent, deters growth of harmful microorganisms on the surface of the skin. The sweat glands may be considered to have an excretory function as water; electrolytes; and cer-tain organic wastes, such as urea, are lost in sweat. Certain drugs are also excreted through sweat.

Compared with merocrine glands, there are few apocrine sweat glands, which are located in thearmpits, around the nipples, in a bearded region (in men), and in the groin area. They start to secrete at puberty and produce a cloudy, sticky secretion, with a characteristic odor. This secretion contains lipids and proteins, in addition to the components of sweat produced by merocrine sweat glands. The apocrine glands are surrounded by myoepithelial cells, which, on contraction, discharge the apocrine secretions into hair follicles. This secretion is a potential nutri-ent for microorganisms and the action of bacteria on this secretion tends to intensify the odor. The apoc-rine glands change in size during the menstrual cy-cle—increasing during ovulation and shrinking at the time of menstruation.

Sebaceous Glands

The sebaceous glands are located close to the hair fol-licles and discharge their secretions into the hair fol-licles. In other areas, such as the lips, glans penis, and labia minora, they discharge directly on to the skin surface. There are no sebaceous glands in the palms and soles. The size of the glands varies from region to region. Large glands are present in the breasts, face, neck, and upper part of the chest. They secrete an oily substance and are sometimes referred to as the oil glands. The secretion, calledsebum, is a mixture of lipids, proteins, and electrolytes. Sebum provides lubrication, protects the keratin of the hair, conditions skin, and prevents excess evaporation of water. These glands are sensitive to sex hormones, and the increase in activity at puberty makes a per-son more prone to acne. Acne is a result of blockage of the sebaceous ducts and inflammation of the seba-ceous glands and surrounding area.

Other Glands of the Skin

The skin also contains other specialized glands found in specific regions. The mammary glands of the breast, related to the apocrine sweat glands, secrete milk. The regulation of milk secretion and ejection is complex and controlled by hormones and nerves.

Specialized glands, known as ceruminous glands, are present in the external auditory canal. These glands are modified sweat glands that secrete ceru-men or earwax.This sticky secretion protects the earfrom foreign particles.

Hair

Hair, or pili, is seen in almost all parts of the body. It originates from structures known as hair follicles, which are found in the dermis. Hair is formed in the follicles by a specialized cornification process and is made up of soft and hard keratin, which gives it its characteristic texture and color. The deepest part of the hair follicle enlarges slightly to form the hair bulb and encloses a network of capillaries and nerves. A strip of smooth muscle, known as the arrector pilimuscle, extends from the upper part of the dermis toconnective tissue surrounding the hair. Stimulation of this muscle makes the hair stand on end (goose pimples, gooseflesh, or goose bumps) and traps a layer of air next to the skin, further helping to insu-late the body.

There are two types of hair. Fine, fuzzy hair is known as vellus hair. The heavy, deeply pigmented hair, as found in the head and eyebrow, is known as terminal hair. The growth of hair is greatly influ-enced by circulating hormones.

Hair has many functions. Scalp hair protects the head from UV rays and serves as insulation. Hair found in the nose, ears, and eyelashes helps prevent entry of larger particles and insects. The nerve plexus surrounding the follicle detects small hair move-ments and senses imminent injury.

Hair color reflects the pigment differences pro-duced by melanocytes in the hair papilla. Although genetics play an important part, hormones and nutri-tion have an important role too. With age, as pigment production decreases, hair appears gray.

Hair grows and sheds according to a hair growth cycle. Hair in the scalp may grow for 2–5 years at the rate of about .33 mm per day. The rate varies from in-dividual to individual. As the hair grows, the nutri-ents required for hair formation are absorbed from the blood. Heavy metals may also be absorbed, and hair samples can be used for identifying lead poison-ing. Hair is, therefore, one of the important speci-mens analyzed in forensic medicine. As a hair reaches the end of the growth cycle, the attachment to the hair follicle weakens and the follicle becomes inactive. Eventually, the hair is shed and a new hair begins to form. Hair loss can be affected by such fac-tors as drugs, diet, radiation, excess vitamin A, stress, and hormonal levels.

Nails

Nails protect the tips of the fingers and toes and limit the distortion when exposed to excess stress. Nails are formed at the nail root, an epithelial fold deeply located near the periosteum of the bone. The body of the nail is composed of dead cells that are packed with keratin. Nail growth can be altered by body me-tabolism. Changes in structure, thickness, and shape can indicate different systemic conditions.

Related Topics