Chapter: The Massage Connection ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY : Integumentary System

The Epidermis - Structure of the Skin

THE EPIDERMIS

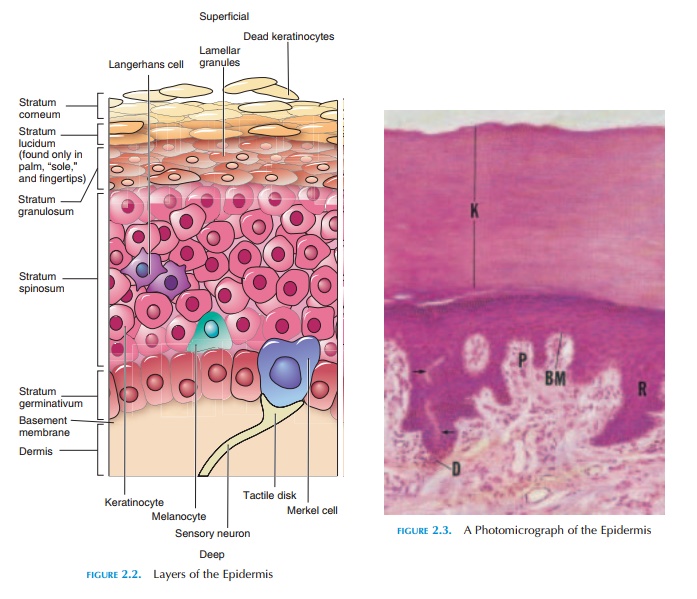

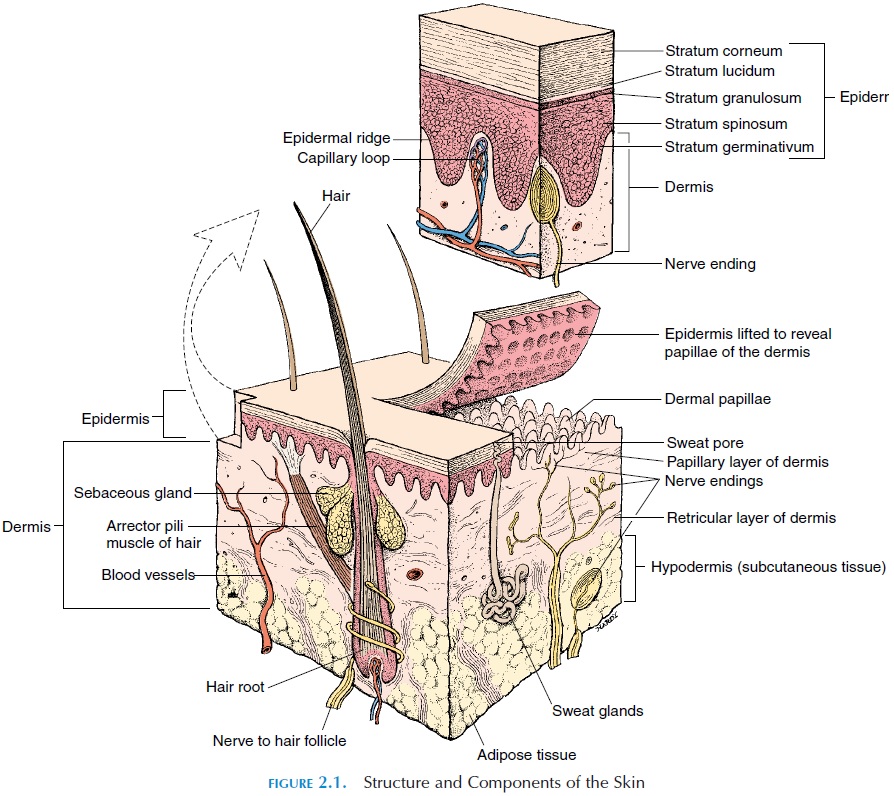

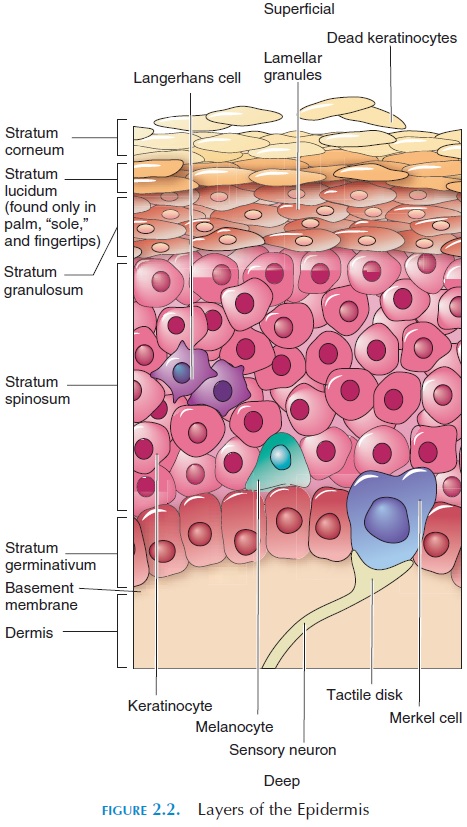

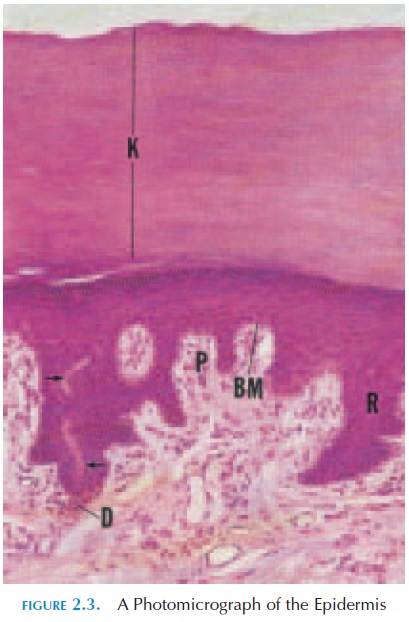

The epidermis (see Figures 2.2 and 2.3) is the most superficial layer of the skin and is composed of strat-ified squamous epithelium. The epidermis is sepa-rated from the dermis—the deeper layer—by the basement membrane. Not having a direct blood sup-ply, the epidermis relies on nutrients in the intersti-tial fluid that have diffused from the capillaries lo-cated in the dermis.

There are four types of skin cells:

· keratinocytes

· melanocytes

· Merkel cells

· Langerhans cells (Figure 2.2).

Keratinocytes make up 90% of the epidermis; they lie in many distinct layers and produce a tough fi-brous protein called keratin. Keratin helps protect the skin from heat, microorganisms, and chemicals in the environment.

The layers of the epidermis can be identified by ex-amining a section under the microscope. Beginning with the basement membrane, which separates the epidermis from the dermis, the following layers can be identified:

· stratum germinativum, or stratum basale

· stratum spinosum

· stratum granulosum

· stratum lucidum

· stratum corneum.

In areas where skin is exposed to friction, such as the palm of the hand, sole of the foot, and fingertips, the skin is thick and consists of all five layers. In other areas, such as the eyelids, the skin is thin and stratum lucidum is absent.

The Stratum Germinativum

This single-celled layer, consisting of cuboidal or columnar epithelium, is attached to the basement membrane. It is thrown into folds known as epider-mal ridges that extend into the dermis (Figure 2.2).The projections of the dermis adjacent to the ridges are known as the dermal papillae. The surface of the skin follows the ridge pattern. This pattern, referred to as whorls, is especially obvious in the palms and soles. These ridges increase friction and surface area, providing a better, more secure grip of objects. The shapes of the ridges are genetically determined and unique to an individual; they do not change with time. For this reason, fingerprints can be used for identification.

As its name suggests, this layer contains germina-tive, or basal cells, that multiply rapidly and replace cells in the superficial layer that have been lost or shed. The keratinocytes are large and contain keratin filaments in the cytoskeleton. The keratin filaments attach the cells to each other and to the basement membrane. Areas of skin that lack hair contain spe-cialized cells known as Merkel cells. These cells are in close contact with touch receptors and stimulate these sensory nerve endings. Pigment cells, known as melanocytes, are also located in this layer and are responsible for the color of the skin. Melanocytes are scattered throughout this layer and their processes extend to the more superficial layers of the skin.

Melanocytes

Melanocytes form 8% of all skin cells and manufac-ture the pigment melanin. Melanocytes contain the enzymes required for converting the amino acid tyro-sine into melanin. The melanin pigment, packaged in-side the cell in small vesicles called melanosomes, is transferred along the processes that extend into the su-perficial layers of skin. In the superficial layers, the vesicles are transferred into other cells, coloring them temporarily, until they fuse with lysosomes and are then destroyed. In individuals with light skin, less transfer of melanosomes occurs among cells, and the superficial layers lose their pigments faster. In individ-uals with dark skin, the melanosomes are larger and transfer occurs in many of the superficial layers. In-terestingly, the number of melanocytes per square mil-limeter of skin is the same for both dark- and light-skinned individuals. It is the melanin synthesis rate that is different. The number of melanocytes is in-creased in some areas of the body, such as the penis, nipples, areolae (area around the nipple), face, and limbs.

The melanin pigment protects the skin from the harmful effects of ultraviolet (UV) radiation. Expo-sure to UV rays stimulates those enzymes that pro-duce melanin and produces a “tan” skin. The tan fades when the keratinocytes containing melanin are lost. Melanin production is also increased by secre-tion of melanocyte-stimulating hormones by the an-terior pituitary gland.

Because melanin pigment is concentrated around the nucleus, it works like an umbrella, absorbing UV rays and shielding the nucleus and its high deoxyri-bonucleic acid (DNA) content. Melanin also protects the skin from sunburn. However, the rate of melanin synthesis is not rapid enough to provide complete protection; it is possible to get a sunburn easily, espe-cially in the first few days of prolonged sun exposure. Mild sunburn consists of varying degrees of redness that appear 2–12 hours after exposure to the sun. Scaling and peeling follow any overexposure to sun-light. Dark skin also burns and may appear grayish or gray–black.

The cumulative effects of UV radiation exposure can damage fibroblasts located in the dermis, leading to faulty manufacture of connective tissue and wrin-kling of the skin. UV rays also stimulate the produc-tion of oxygen free radicals that disrupt collagen and elastic fibers in the extracellular regions. Although a small amount of UV radiation is beneficial, larger amounts may cause alterations in the genetic mater-ial in the nucleus of cells—especially the rapidly mul-tiplying cells in the stratum germinativum, increas-ing the risk of cancer. Depletion of the ozone layer and overexposure to the sun may be responsible for increased incidence of skin cancer.

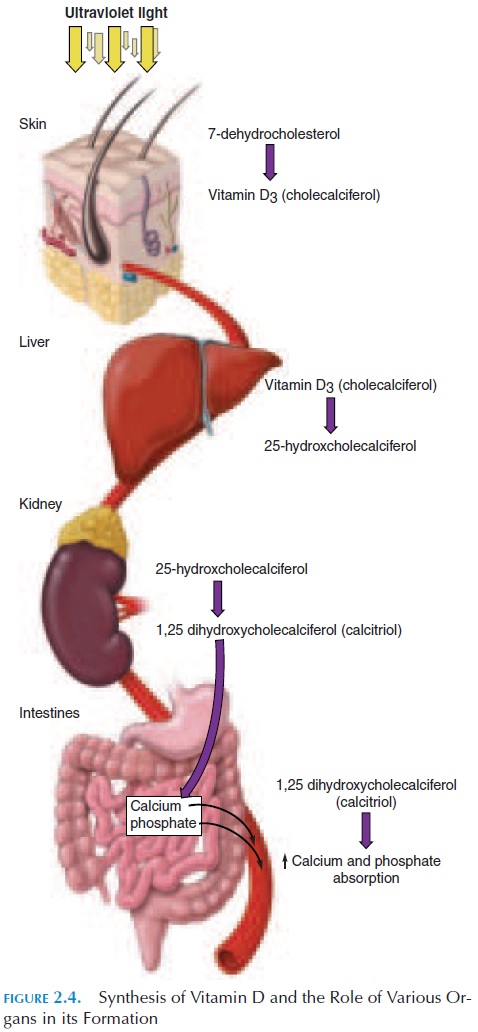

Synthesis of Vitamin D

Excessive exposure to sunlight is harmful; however, some exposure to sunlight is useful and needed by the body. The cells in the stratum germinativum and stratum spinosum convert the compound 7-dehydro-cholesterol into a precursor of vitamin D. Vitamin D is a group of closely related steroids produced by the action of ultraviolet light on 7-dehydrocholesterol. Vitamin D synthesized in the skin is transported to the liver and then to the kidneys where it is converted into a more potent form (see Figure 2.4). Vitamin D increases calcium absorption in the intestines and is an important hormone in calcium metabolism. Lack of vitamin D can lead to improper bone mineraliza-tion and a disease called rickets (in children) and os-teomalacia (in adults).

Stratum Spinosum

Stratum spinosum consists of 8–10 layers of cells lo-cated immediately above the stratum germinativum. As the cells multiply in the stratum germinativum, they are pushed upward into the stratum spinosum. Observed under the microscope, these cells have a spiny appearance, hence, their name. This layer of cells, in addition to keratinocytes, contains Langer-hans cells, which are involved in defense mecha-nisms. Langerhans cells protect the skin from pathogens and destroy abnormal cells, such as cancer cells, that may be present.

Stratum Granulosum

Stratum granulosum consists of 3–5 layers. By the time the keratinocytes reach this layer from the lay-ers below, they have flattened and stopped dividing. The cells have a granular appearance when viewed under the microscope and contain a granular protein known as keratohyalin, which organizes keratin into thicker bundles. The cells also contain lamellargranules, which release a lipid-rich secretion intothe spaces between the cells. These lipid-rich secre-tions work as a sealant and slow the loss of body flu- ids. As the cells manufacture keratohyalin, they be-come flatter and thinner and the cell membranes become thicker and impermeable to water. With time, a thick layer of interlocking keratin fibers sur-rounded by keratohyalin may be seen within the cell membrane of the original cells, which have now lost their organelles. These structural changes provide protection against pathogens and are responsible for the impermeability of skin to water.

Stratum Lucidum

Stratum lucidum, as its name indicates, is translu-cent and consists of densely packed, flat cells that are filled with keratin. This layer is more prominent in the palms of the hands and soles of the feet.

Stratum Corneum

Stratum corneum is the most superficial layer and mostly consists of dead cells and keratin. The trans-formation from live cells to the dead cells in this layer is known askeratinization, or cornification (corne, hard or hooflike). There are about 15–30 layers ofthese cells, which are periodically shed individually or in sheets. It usually takes about 15–30 days for the cells to reach this layer from the stratum germina-tivum. The cells then remain in the stratum corneum for about 14 days before they are shed. The dryness of this superficial layer, together with the coating of lipid secretions from sebaceous and sweat glands, makes the skin unsuitable for growth of microorgan-isms. If the skin is exposed to excessive friction, the layer abnormally thickens and forms a callus.

Although dead cells make the skin resistant to wa-ter, it does not prevent the loss of water by evapora-tion from the interstitial tissue. About 500 mL of wa-ter per day is lost via the skin. This loss of water is known as insensible perspiration, which is different from that actively lost by sweating, called sensibleperspiration.

Promotion of Epidermal Growth

Epidermal growth is promoted by a peptide known as epidermal growth factor (EGF). EGF is secreted by various tissues, such as the salivary gland and glands in the duodenum. This factor combines with receptors on the cell membrane of multiplying cells in the epidermis and promotes cell division, produc-tion of keratin, and development and repair after in-jury. So potent, a small sample of EGF from a per-son’s tissue has been used outside the body to form sheets of epidermal cells to cover severe burns.

Related Topics