Chapter: Medical Microbiology: An Introduction to Infectious Diseases: Upper Respiratory Tract Infections and Stomatitis

Upper Respiratory Tract Infections and Stomatitis

Upper Respiratory Tract Infections and Stomatitis

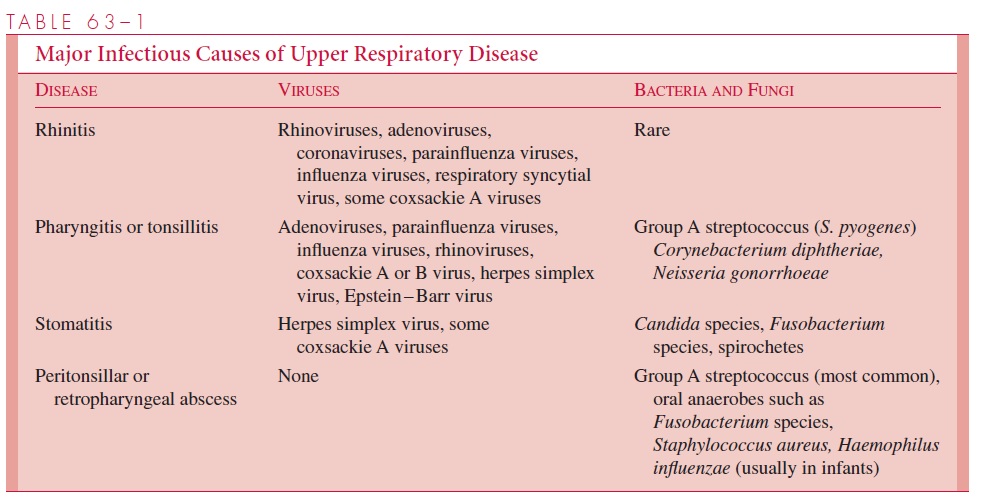

Upper respiratory infections usually involve the nasal cavity and pharynx, and most (more than 80%) are caused by viruses. Like middle and lower respiratory illnesses, the diseases of the upper respiratory tract are named according to the anatomic sites primarily involved. Rhinitis (or coryza) implies inflammation of the nasal mucosa,pharyngitis denotes pharyngeal infection, and tonsillitis indicates an inflammatory involvement of the tonsils. Because of the close proximity of these structures to one another, infections may simultaneously involve two or more sites (eg, rhinopharyngitis or tonsillopharyngitis). All such infections are grouped under the general term upper respiratory infections. Stomatitis is a term used to describe infections primarily localized to the mucous membranes of the oral cavity. These infections can sometimes also involve the tongue (glossitis) or the gingival and periodontal tissues (gingivostomatitis or acute necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis;) Other infections considered are peritonsillar abscess (quinsy), retrotonsillar abscess, and retropharyngeal abscess. These infections are the result of direct invasion from mucosal sites and localization in deeper tissues to produce inflammation and abscess formation.

CLINICAL FEATURES

Rhinitis is the most common manifestation of the common cold. It is characterized byvariable fever, inflammatory edema of the nasal mucosa, and an increase in mucous se-cretions. The net result is varying degrees of nasal obstruction; the nasal discharge may be clear and watery at the onset of illness, becoming thick and sometimes purulent as the infection progresses over 5 to 10 days.

Pharyngitis and tonsillitis are associated with pharyngeal pain (sore throat) and theclinical appearance of erythema and swelling of the affected tissues. There may be exu-dates, consisting of inflammatory cells overlying the mucous membrane, and petechial hemorrhages; the latter may be seen in viral infections but tend to be more prominent in bacterial infections. Viral infections, particularly herpes simplex, may also lead to the formation of vesicles in the mucosa, which quickly rupture to leave ulcers. Pharyngeal candidiasis can also erode the mucosa under the plaques of “thrush.” On rare occasions, the local inflammation may be sufficiently severe to producepseudomembranes, which consist of necrotic tissue, inflammatory cells, and bacteria. This finding is particularly common in pharyngeal diphtheria, but may be mimicked by fusospirochetal infection (Vincent’s angina) and sometimes by infectious mononucleosis. In acute tonsillitis or pharyngitis of any etiology, regional spread of the infecting agents with inflammation and tender swelling of the anterior cervical lymph nodes is also common.

Stomatitis is inflammation of the oral cavity. Multiple ulcerative lesions of the oralmucosa, seen most frequently with severe primary herpes simplex infections, may extend to the tongue, lips, and face. In extreme cases, the pain may be so severe that the patient requires relief with topical anesthetics during the usual 9- to 12-day period of acute symptoms. Candida species can also invade oral surfaces to produce plaques identical to those of pharyngeal thrush. This infection is particularly common in young infants and immunocompromised individuals of any age.

Aphthous stomatitis is a recurrent disease of the oral mucosa characterized by singleor multiple painful ulcers with irregular margins, usually 2 to 10 mm in diameter. Healing usually occurs in a few days. The term commonly used to describe this condition is canker sore. The cause is unknown. It can easily be confused with recurrent herpes sim-plex lesions and, like herpes, tends to recur in relation to stress, menses, local trauma, and other nonspecific stimuli.

A severe, gangrenous stomatitis that progresses beyond the mucous membranes to involve soft tissues, skin, and sometimes bone can complicate a variety of acute ill-nesses in patients who are severely debilitated and whose oral hygiene is poor. This infection, called noma or cancrum oris, is rarely seen in the United States. Typical cases occur among children with severe protein – calorie malnutrition or other immune compromise. Measles sometimes precipitates noma. Etiologic agents thought to be involved include Fusobacterium and Bacteroides species, as well as Pseudomonasaeruginosa. Milder forms of stomatitis are seen in a variety of other common viralinfections. Examples include Koplik’s spots in measles, buccal or palatal ulcers in chickenpox, and similar phenomena in some enteroviral infections such as hand, foot, and mouth disease.

Peritonsillar or retrotonsillar abscesses are usually a complication of tonsillitis. They are manifested by local pain, and examination of the pharynx reveals tonsillar asymmetry with one tonsil usually displaced medially by the abscess. This infection is most common in children more than 5 years of age and in young adults. If not properly treated, the ab-scess may spread to adjacent structures. It can involve the jugular venous system, erode into branches of the carotid artery to cause acute hemorrhage, or rupture into the pharynx to produce severe aspiration pneumonia.

Retropharyngeal or lateral pharyngeal abscesses occur most frequently in infants and children less than 5 years of age. They can result from pharyngitis or from accidental per-foration of the pharyngeal wall by a foreign body. The infection is characterized by pain, inability or unwillingness to swallow, and, if the pharyngeal wall is displaced anteriorly near the palate, a change in phonation (nasal speech). The neck may be held in an ex-tended position to relieve pain and maintain an open upper airway. Examination of the pharynx usually reveals anterior bulging of the pharyngeal wall; if this finding is not ap-parent, lateral x-rays of the neck may demonstrate a widening of the space between the cervical spine and the posterior pharyngeal wall. The complications of such abscesses are basically the same as those described for peritonsillar abscesses; in addition, the suppura-tive process can extend posteriorly to the cervical spine to produce osteomyelitis or infe-riorly to cause acute mediastinitis.

In the immunocompromised patient, all of the various forms of stomatitis and pharyngitis described previously can be accentuated. Leukemia, agranulocytosis, chronic ulcerative colitis, congenital or acquired immunodeficiency (eg, AIDS), and treatment with cytotoxic or immunosuppressive drugs are commonly associated with such lesions. The marked damage to mucosal tissues that sometimes occurs can provide a portal of entry into deeper structures and then to the systemic circulation, creating a risk of bacterial or fungal sepsis. Conversely, oral lesions may also result from dissemi-nation of infection from other remote sites. Examples include disseminated histoplasmo-sis and sepsis caused by Pseudomonas species.

COMMON ETIOLOGIC AGENTS

Table 63 – 1 lists the more common causes of upper respiratory infections and stomatitis. Viral infections predominate. The most frequent bacterial cause to be considered is S. pyogenes. Corynebacterium diphtheriae, although rare in the United States, is a majorpathogen that continues to cause infection in many other countries and must not be over-looked, particularly if clinical and epidemiologic findings suggest this possibility. Neisseria gonorrhoeae, isolated from adults with symptomatic pharyngitis in whom noother etiologic agent can be demonstrated, is now considered a pharyngeal pathogen that is usually transmitted by oral – genital contact. Occasionally, other bacteria have been im-plicated as causes of acute pharyngitis (eg, Corynebacterium ulcerans, Arcanobacteriumhaemolyticum, Francisella tularensis, and streptococci of groups B, C, and G). These arelisted here for the sake of completeness but are not routinely sought except in unusual circumstances.

In patients with purulent rhinitis, sinusitis should also be considered in the differential diagnosis . Unilateral and foul-smelling purulent discharge suggests the presence of a foreign body in the nose.

GENERAL DIAGNOSTIC APPROACHES

Although viruses cause the vast majority of upper respiratory infections, they are gener-ally not amenable to specific therapy, and laboratory tests for viral infections are usually reserved for investigating outbreaks or in cases in which the illness seems unusually se-vere or atypical.

The primary diagnostic approach in pharyngitis and tonsillitis is to determine whether there is a bacterial cause requiring specific treatment. The only reliable method is to col-lect a throat swab for culture, taking care to thoroughly swab the tonsillar fauces as well as the posterior pharynx, and to include any purulent material from inflamed areas. Cul-tures are usually made only to detect the presence or absence of group A streptococci. Di-rect antigen tests for rapidly detecting S. pyogenes in throat swabs have gained popularity in recent years. These are usually enzyme immunoassay or latex agglutination – based methods. The most common limitation of such tests is lack of sensitivity; that is, false-negative results can occur.

For the laboratory diagnosis of diphtheria or pharyngeal gonorrhea, the clinical suspi-cion should be indicated to the laboratory so that specific cultures for C. diphtheriaeor N. gonorrhoeae may be made. Candida species, fusospirochetal bacteria, Pseudomonas species, and other Gram-negative organisms are often found in pharyngeal or oral speci-mens from healthy individuals as well as in certain infections. Their probable pathogenic significance in association with disease in these sites, largely based on the appearance of the lesions and the presence of the organisms in large numbers, can be supported by his-tologic demonstration of tissue invasion by the organisms. It is important to remember that other bacterial pathogens such as Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus,Haemophilus influenzae, and even Neisseria meningitidismay be present in the pharynx.These organisms are not primary etiologic agents in rhinitis, pharyngitis, and tonsillitis, and their presence in the throat does not implicate them as causes of the illnesses; they should instead be regarded as colonizers.

The laboratory diagnosis of causes of peritonsillar and retropharyngeal abscesses is based on Gram staining and culture of purulent material obtained directly from the lesion, including anaerobic cultures.

GENERAL PRINCIPLES OF MANAGEMENT

Viral infections of the upper respiratory tract can only be treated symptomatically. If S.pyogenes is the cause, penicillin therapy is required; if the patient is allergic to peni-cillin, an alternative is chosen (eg, erythromycin or a cephalosporin). Such treatment prevents suppurative or toxigenic complications (eg, pharyngeal abscess, cervical adeni-tis, and scarlet fever) and the development of acute rheumatic fever. The latter, a serious complication, may occur in 1 to 3% of patients in certain population groups if they are not adequately treated. In addition, treatment of acute streptococcal infections can aid in reducing spread of the organisms to other persons.

C. diphtheriae infections involve more complex management, which includes anti-toxin as well as antimicrobic treatment . Infections caused by N. gonor-rhoeae are treated with appropriate antimicrobics . The management ofstomatitis includes maintenance of adequate oral hygiene. If invasive Candida infection is present, topical and/or systemic antifungal therapy is sometimes necessary. Vincent’s angina and other fusospirochetal infections are usually treated with systemic penicillin therapy as well as with appropriate dental and periodontal care. There is no specific, widely accepted treatment for aphthous stomatitis. Peritonsillar and retropharyngeal ab-scesses are treated aggressively with antimicrobics and often require surgical drainage, taking care to prevent accidental aspiration of the abscess contents into the lower respira-tory tract.

Related Topics