Chapter: Medical Microbiology: An Introduction to Infectious Diseases: Trematodes

Trematodes

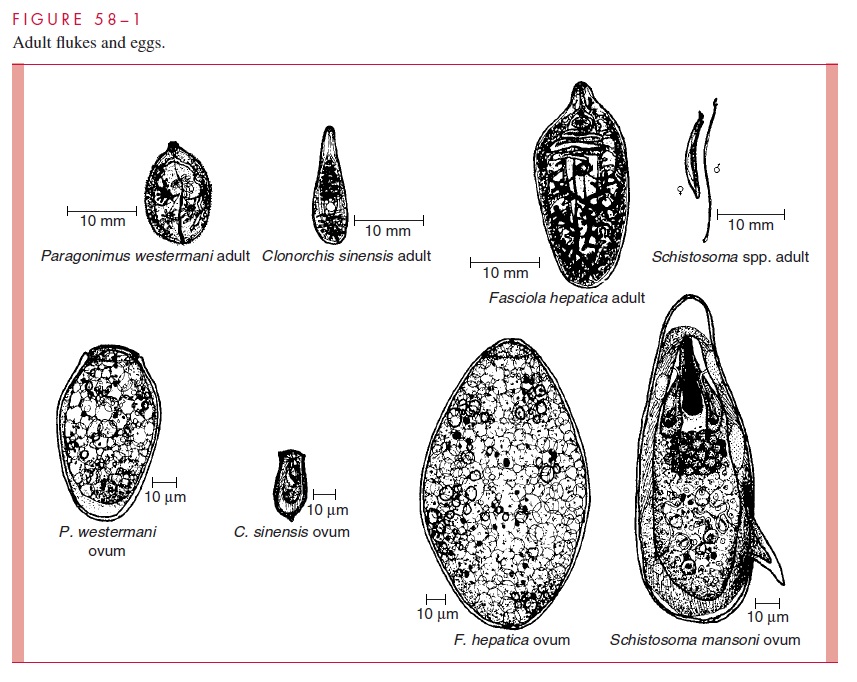

Of the myriad relationships that have developed between helminths and humans overthe millennia of our mutual existence, none has proved more destructive to our health and productivity than that forged with the indomitable flukes. Typically, the adults live for decades within human tissues and vascular systems, where they resist immunologic attack and produce progressive damage to vital organs. Morphologically, trematodes are bilaterally symmetric, vary in length from a few millimeters to several centimeters, and possess two deep suckers from which they derive their name (“body with holes”). One surrounds the oral cavity, and the other is located on the ventral surface of the worm. These organs are used for both attachment and locomotion; movement is effected in a characteristic inchworm fashion. The digestive tract begins at the oral sucker and contin-ues as a muscular pharynx and esophagus before bifurcating to form bilateral ceca that end blindly near the posterior extremity of the worm. Undigested food is vomited out through the oral cavity. The excretory system consists of a number of hollow, ciliated flame cells that excrete waste products into interconnecting ducts terminating in a poste-rior excretory pore.

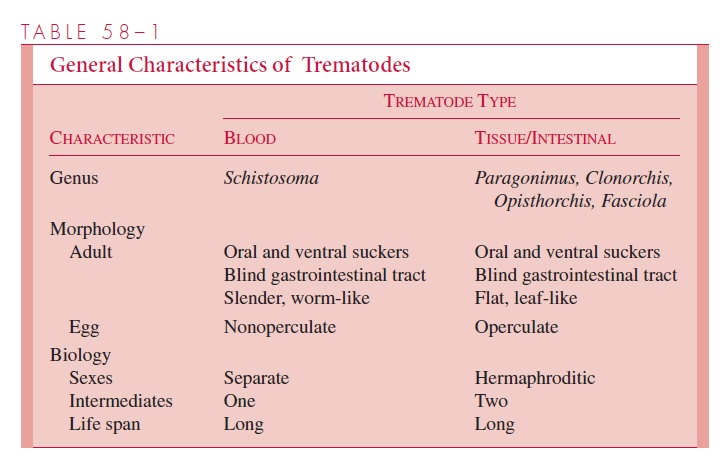

The reproductive systems vary and serve as a means for dividing the trematodes into two major categories: the hermaphrodites and the schistosomes. The adult hermaphrodite contains both male and female gonads and produces operculate eggs. The schistosomes have separate sexes, and the fertilized female deposits only nonoperculated offspring. The two groups have similar life cycles. The major differential features are summarized in Table 58 – 1. Eggs are excreted from the human host and, if they reach fresh water, hatch to release ciliated larvae called miracidia. These larvae find and penetrate a snail host spe-cific for the trematode species. In this intermediate host, they are transformed by a process of asexual reproduction into thousands of tail-bearing larvae or cercariae, which are released from the snail over a period of weeks and swim about vigorously in search of their next host. In the case of schistosomal cercariae, this host is the human. When they come in contact with the skin surface, they attach, discard their tails, and invade, thereby completing their life cycle. The cercariae of the hermaphroditic flukes encyst in or on an aquatic plant or animal, where they undergo a second transformation to become infective metacercariae. Their cycle is completed when the second intermediate host is ingested by a human.

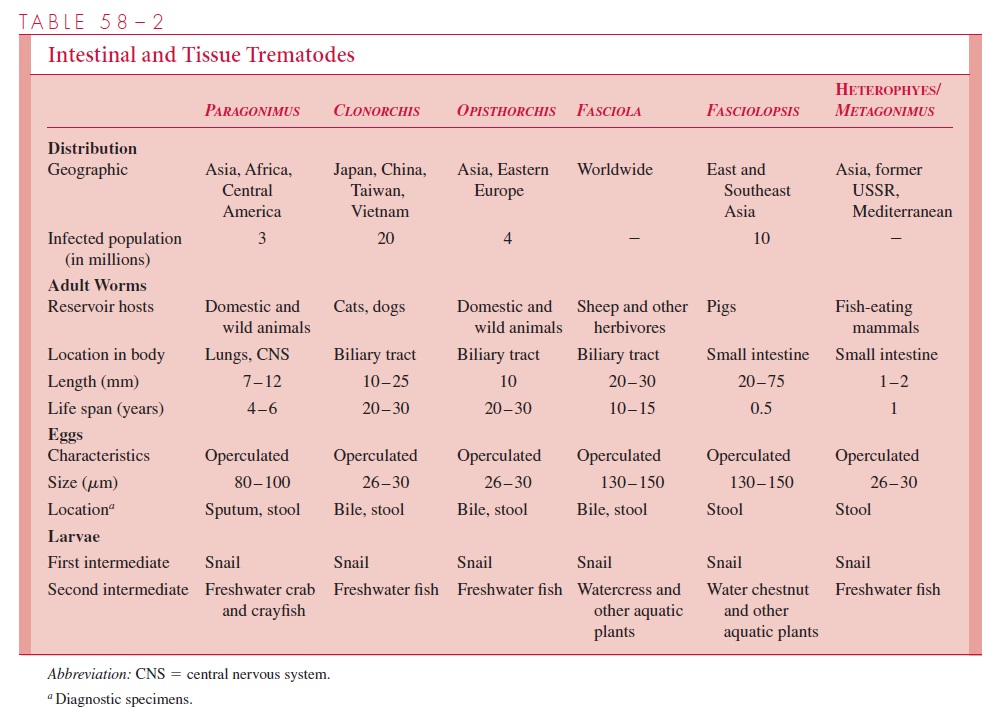

Of the many trematodes that infect humans, only five are discussed: the blood flukes, all of which are members of the genusSchistosoma (S. mansoni, S. haematobium, and S. japonicum); and the lung (Paragonimus spp.) and liver (Clonorchis sinensis) flukes,which are hermaphroditic (Fig 58 – 1). Basic details of other hermaphroditic tissue and in-testinal flukes are listed in Table 58 – 2.

Related Topics