Chapter: Clinical Dermatology: Medical treatment

Topical treatment

Topical

treatment

Percutaneous absorption

A

drug used on the skin must be dissolved or sus-pended in a vehicle (base). The

choice of the drug and of the vehicle are both important and depend on the

diagnosis and the state of the skin. For a drug to be effective topically, it

must pass the barrier to diffusion presented by the horny layer . This requires

the drug to be transferred from its vehicle to the horny layer, from which it

will diffuse through the epidermis into the papillary dermis. Passage through

the horny layer is the rate-limiting step.

The

transfer of a drug from its vehicle to the horny layer depends on its relative

solubility in each (measured as the ‘partition coefficient’). Movement across

the horny layer depends both upon the concentration gradient and on restricting

forces (its ‘diffusion constant’). In general, non-polar substances penetrate

more rapidly than polar ones. A rise in skin temperature and in hydration, both

achieved by covering a treated area with polyethylene occlusion, encourages

penetration.

Some

areas of skin present less of a barrier than do others. Two extreme examples

are palmar skin, with its impermeable thick horny layer, and scrotal skin,

which is thin and highly permeable. The skin of the face is more permeable than

the skin of the body. Body fold skin is more permeable than nearby unoc-cluded

skin. In humans, absorption through the hair follicles and sweat ducts is of

little significance and the amount of hair on the treated site is no guide to

its permeability.

In

many skin diseases, the horny layer becomes abnormal and loses some of its

barrier function. The abnormal nucleated (parakeratotic) horny layers of

psoriasis and chronic eczema, although thicker than normal, have lost much of

their protective qualities. Water loss is increased and therapeutic agents

penet-rate more readily. Similarly, breakdown of the horny layer by chemicals

(e.g. soaps and detergents) and by physical injury will allow drugs to

penetrate more easily.

In

summary, the penetration of a drug through the skin depends on the following

factors:

•

its concentration;

•

the base;

•

its partition coefficient;

•

its diffusion constant;

•

the thickness of the horny layer;

•

the state, including hydration, of

the horny layer; and

•

temperature.

Active ingredients

These

include corticosteroids, tar, dithranol, anti-biotics, antifungal and antiviral

agents, benzoyl per-oxide, retinoic acid and many others. The choice depends on

the action required, and prescribers should know how each works. As topical

steroids are the mainstay of much local derma-tological therapy, their

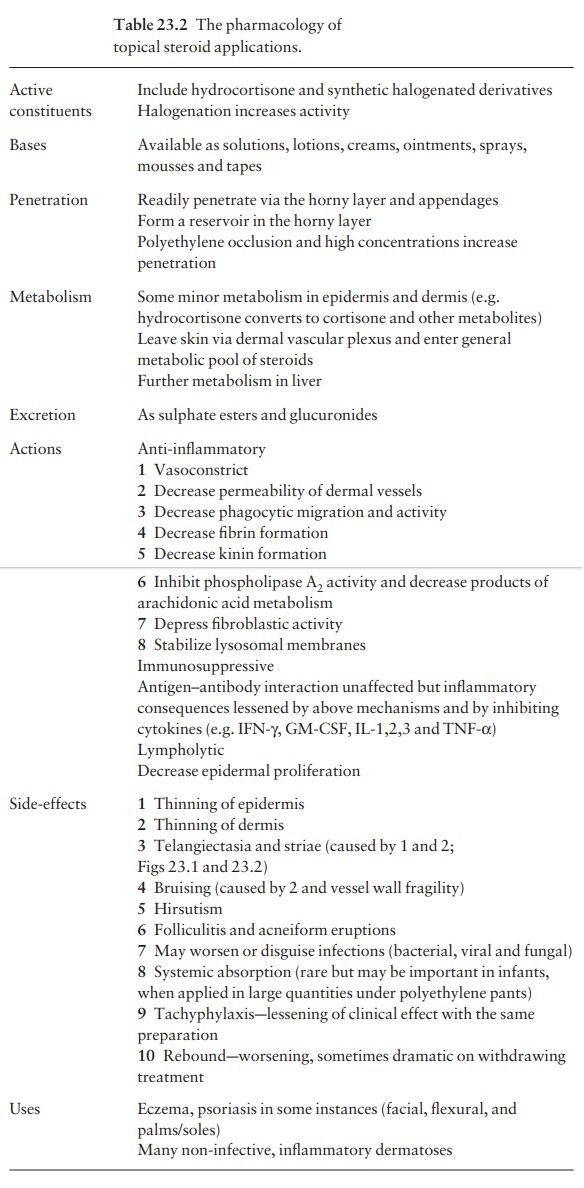

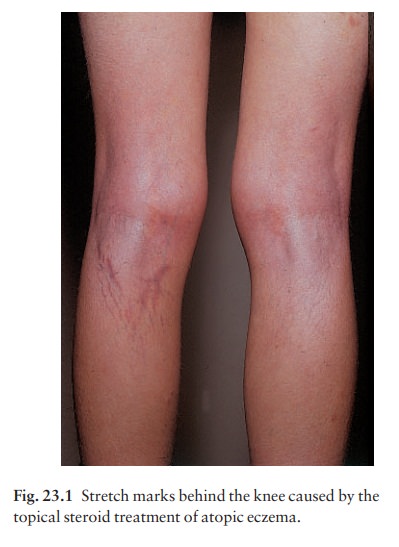

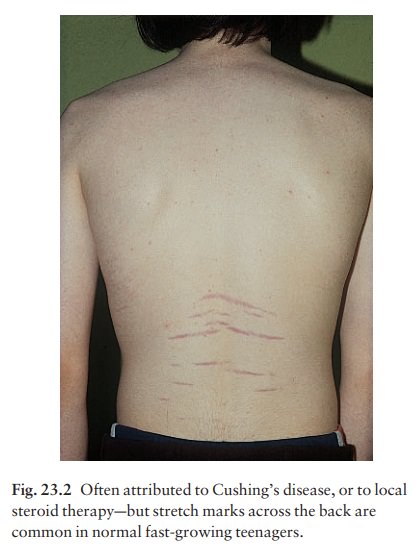

pharmacology is summarized in Table 23.2.

Vehicles (bases)

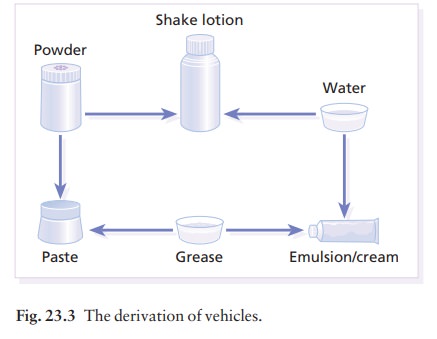

Most

vehicles are a mixture of powders, water and greases (usually obtained from

petroleum). Figure 23.3 shows that blending these bases together produces

preparations that retain the characteristics of each of their components.

A

vehicle should maximize the delivery of top-ical drugs but may also have useful

properties in its own right. Used carelessly, vehicles may even do harm.

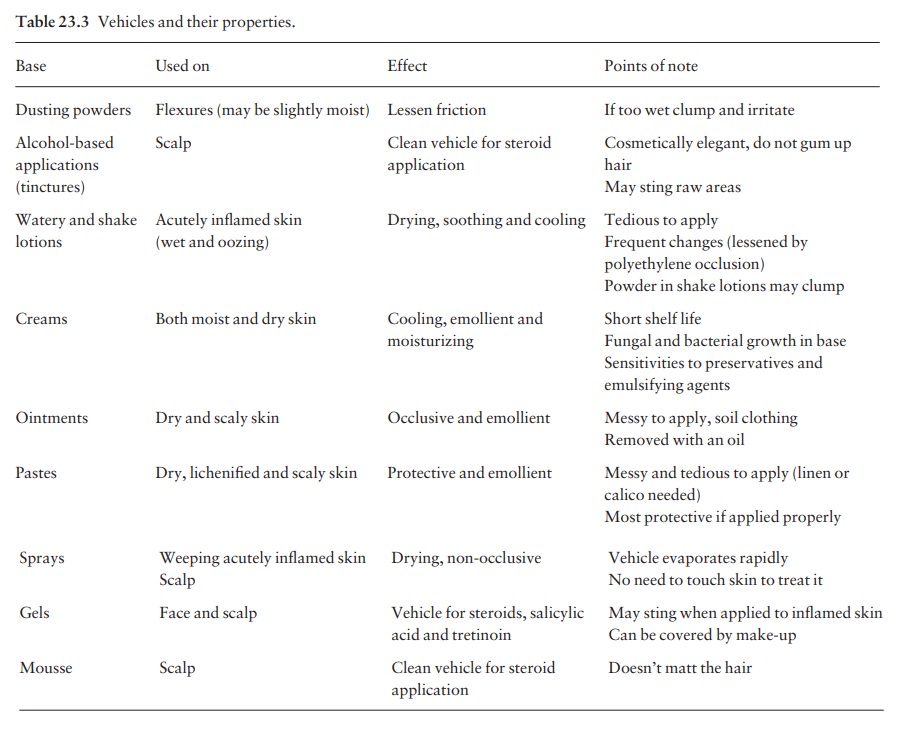

Suggested indications are shown in Table 23.3. The choice of vehicle depends

upon the action desired, availability, messiness, ease of application and cost.

Individual vehicles

Dusting

powders are used in the folds to lessen fric-tion between opposing surfaces.

They may repel water (e.g. talc) or absorb it (e.g. starch); zinc oxide powder

has an absorptive power midway between these extremes. Powders ought not be

used in moist areas where they tend to cake and abrade.

Watery

lotions evaporate and cool inflamed areas. This effect is hastened by adding an

alcohol, but glyc-erol or arachis oil slow evaporation and retain skin

moisture. Substances that precipitate protein (astrin-gents; e.g. silver

nitrate) lessen exudation.

Shake

lotions are watery lotions to which powder has been added so that the area for

evaporation is increased. These lotions dry wet weeping skin. When water has

evaporated from the skin, the powder particles clump together and may become

abrasive. This is less likely if an oil such as glycerol has been added.

Creams are used for their cooling, moisturizing and emollient effects. They are either oil-in-water emulsions [e.g. aqueous cream (UK), acid mantle cream (USA)] or water-in-oil emulsions [e.g. oily cream (UK), cold cream (USA)]. Emulsifying agents are added to in-crease the surface area of the dispersed phase and that of any therapeutic agent in it.

Ointments

are used for their occlusive and emol-lient properties. They allow the skin to

remain supple by preventing the evaporation of water from the horny layer.

There are three main types:

1 those

that are water-soluble (macrogols, polyethy-lene glycols);

2

those that emulsify with water; and

3 those that

repel water (mineral oils, and animal andvegetable fats).

Pastes

are used for their protective and emollient properties and usually are made of

powder added to a mineral oil or grease. The powder lessens the oil’s occlusive

effect.

Variations

on these themes have led to the numer-ous topical preparations available today.

Rather thanuse them all, and risk confusion, doctors should limit their choice

to one or two from each category. Table 23.3 summarizes the properties and uses

of some common preparations.

Preservatives

Water-in-oil

emulsions, such as ointments, require no preservatives. However, many creams

are oil-in-water emulsions that permit contaminating organ-isms to spread in a

continuous watery phase. These preparations therefore, as well as lotions and

gels, require the incorporation of preservatives. Those in common use include

the parahydroxybenzoic acid esters (parabens), chlorocresol, sorbic acid and

propy-lene glycol. Some puzzling reactions to topical pre-parations are based

on allergy to the preservatives they contain

Methods of application

Ointments

and creams are usually applied sparingly twice daily, but the frequency of

their application will depend on many factors including the nature, severity

and duration of the rash, the sites involved, conveni-ence, the preparation

(some new local steroids need only be applied once daily; Formulary 1) and,

most important, on common sense. In extensive erup-tions, a tubular gauze cover

keeps clothes clean and hampers scratching (see Fig. 7.19).

Three

techniques of application are more special-ized: immersion therapy by bathing,

wet dressings (compresses) and occlusive therapy.

Bathing

Once-daily

bathing helps to remove crusts, scales and medications. After soaking for about

10 min, the skin should be rubbed gently with a sponge, flannel or soft cloth;

cleaning may be made easier by soaps, oils or colloidal oatmeal.

Medicated

baths are occasionally helpful, the most common ingredients added to the bath

water being bath oils, antiseptics and solutions of coal tar.

After

cleaning, the most important function of a bath is hydration. The skin absorbs

water and this can be held in the skin for some time if an occlusive oint-ment

is applied after bathing.

Older

patients may need help to get into a bath and should be warned about falling if

the bath contains an oil or another slippery substance.

Wet dressings (compresses)

These

are used to clean the skin or to deliver a topical medication. They are

especially helpful for weeping, crusting and purulent conditions such as

eczema,. Five or six layers of soft cloth (e.g. cotton gauze) are soaked in the

solution to be used; this may be tap water, saline, an astringent or antiseptic

solution, and the compress is then applied to the skin. Open dressings allow

the water to evaporate and the skin to cool. They should be changed frequently,

e.g. every 15 min for 1 h.

Closed dressings are covered with a plastic (usually polyethylene) sheet; they do not dry out so quickly and are usually changed twice daily. They are especially helpful for debriding adherent crusts and for draining exudative and purulent ulcers.

Occlusive therapy

Sometimes

steroid-sensitive dermatoses will respond to a steroid only when it is applied

under a plastic sheet to encourage penetration. This technique is best reserved

for the short-term treatment of stubborn localized rashes. The drawback of this

treatment is that the side-effects of topical steroid treatment (Table 23.2)

are highly likely to occur. The most important is systemic absorption if a

large surface area of skin, relative to body weight, is treated (e.g. when

steroids are applied under the polyethylene pants of infants).

Monitoring local treatment

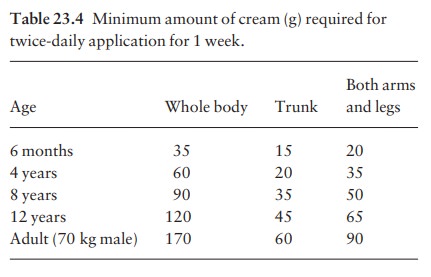

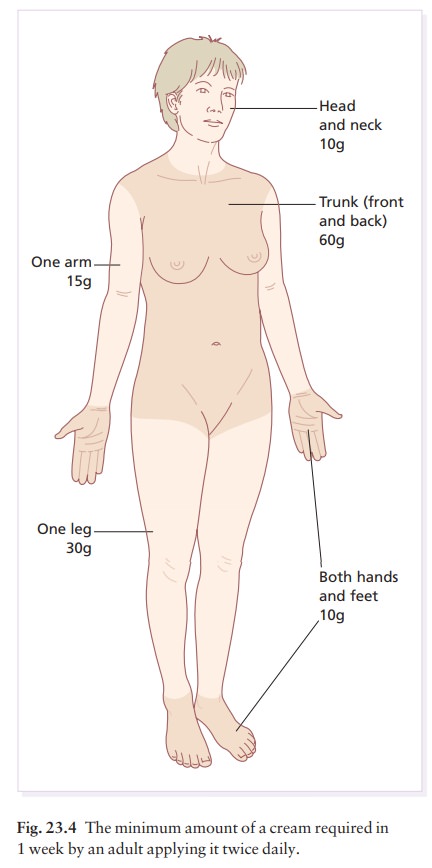

One

common fault is to underestimate the amount required. The guidelines given in

Table 23.4 and Fig. 23.4 are based on twice daily applications. Lotions go

further than creams, which go further than oint-ments and pastes.

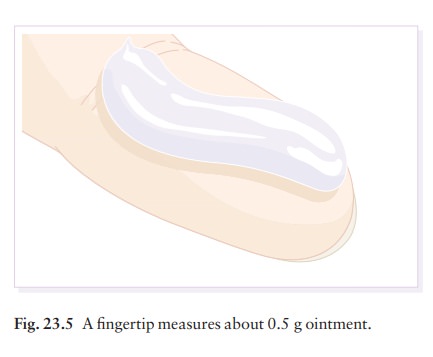

Pump dispensers have recently become available for some topical steroids which allow measured amounts to be applied. Alternatively, ‘fingertip units’ (Fig. 23.5) can increase the accuracy of prescribing. As a guide, You know how much digoxin your patients are taking, but do you know how much of a topical corticosteroid they are applying? Keep a check on this.

one

fingertip unit in an adult male from a standard nozzle provides 0.5 g ointment.

Related Topics