Chapter: Clinical Anesthesiology: Perioperative & Critical Care Medicine: Thermoregulation, Hypothermia, & Malignant Hyperthermia

Thermoregulation & Hypothermia

THERMOREGULATION

& HYPOTHERMIA

Hypothermia,

usually definedasabody tempera-ture less than

36°C, occurs frequently

during anes-thesia and surgery. Unintentional perioperative hypothermia is more

common in patients at the extremes of age, and in those undergoing abdominal

surgery or procedures of long duration, especially with cold ambient operating

room temperatures; it will occur in nearly every such patient unless steps are

taken to prevent this complication.

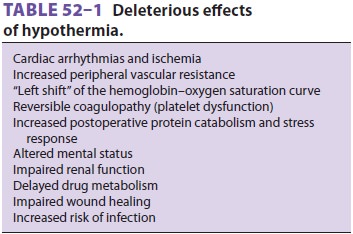

Hypothermia reduces metabolic oxygen requirements and can be protective

during cere-bral or cardiac ischemia. Nevertheless, hypother-mia has multiple deleterious physiological effects (Table 52–1). Infact,

unintendedperioperativehypothermia has been associated with an increased

mortality rate.

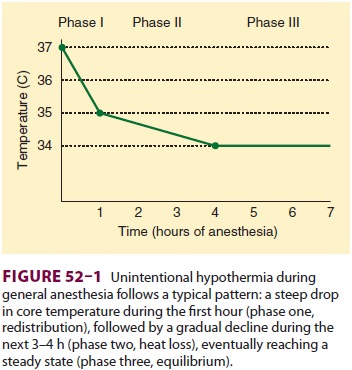

Core temperature is normally the same as the

central venous blood temperature (except during periods of relatively rapid

temperature change as can occur during extracorporeal perfusion). When there is

no attempt to actively warm an anesthetized patient, core temperature usually

decreases 1–2C during the first hour of general anesthesia (phase one), followed

by a more gradual decline during the ensuing 3–4 h (phase two), eventually

reaching a point of steady state (phase three). With general, epidural, or

spinal anesthesia redistribution of heat from warm “central” compartments (eg,

abdomen, thorax) to cooler peripheral tissues (eg, arms, legs) from

anesthetic-induced vasodilation explains most of the initial decrease in

temperature

during phase one, with actual heat loss from

the patient to the environment being a minor contribu-tor. Continuous heat loss

to the environment appears to be primarily responsible for the slower

subse-quent decline during phase two. At steady state, heat loss equals

metabolic heat production (Figure 52–1).In the normal unanesthetized patient

the hypothalamus maintains core body temperature within very narrow tolerances,

termed the interthreshold range, with the threshold for sweating and

vasodilation at one extreme and the threshold for vasoconstriction and

shivering at the other. Increasing core temperature a fraction of a degree

induces sweating and vasodilation, whereas a mini-mally reduced core

temperature triggers vasoconstriction and shivering. Anesthetic agents inhibit

central thermoregulation by interfering with these hypothalamic reflex

responses. For example, isoflurane produces a dose-dependent decrease in the

threshold temperature that triggers vasoconstriction (3C decrease for each

percent of inhaled isoflurane). Both general and regional anesthetics increase

the interthreshold range, albeit by different mechanisms. Spinal and epidural

anes-thetics, like general anesthetics, lead to hypothermia by causing

vasodilation and internal redistribu-tion of heat. The accompanying thermoregulatory

impairment from regional anesthetics that allows continued heat loss is

likely due to altered percep-tion by the hypothalamus of temperature in the

anesthetized dermatomes rather than a central drug effect, as with general

anesthetics.

Intraoperative Considerations

A cold ambient temperature in the operating

room, prolonged exposure of a large wound, and the use of large amounts of

room-temperature intravenous fluids or high flows of unhumidified gases can

con-tribute to hypothermia. Prewarming the patient

forhalf an hour with convective forced-air warming

blankets prevents phase one

hypothermia by elim-inating the central–peripheral temperature gradi-ent. Methods tominimizephase twohypothermiafrom heat loss during anesthesia

include use of forced-air warming blankets and warm-water blan-kets, heated

humidification of inspired gases, warm-ing of intravenous fluids, and

increasing ambient operating room temperature. Passive insulators such as

heated cotton blankets or so-called space blankets have limited utility unless

virtually the entire body is covered.

Postoperative Considerations

Shivering can occur in postanesthesia care

units (PACUs) or critical care units as a result of actual hypothermia or

neurological aftereffects of general anesthetic agents. Shivering is also

common imme-diately postpartum. Shivering in such instances rep-resents the

body’s effort to increase heat production and raise body temperature and may be

associated with intense vasoconstriction. Emergence from even brief general anesthesia

is sometimes also associated with shivering. Although the shivering can be part

of nonspecific neurological signs (posturing, clonus, or the Babinski sign)

that are sometimes observed during emergence, shivering is most often

associ-ated with hypothermia and volatile anesthetics. Regardless of the

mechanism, shivering appears to be more common after longer durations of

surgery and the use of greater concentrations of a volatile agent. Occasionally

it is intense enough to cause hyperthermia (38–39°C) and metabolic acidosis, both of which

promptly resolve when the shivering stops. Both spinal and epidural anesthesia

lower th shivering threshold and vasoconstrictive response to hypothermia;

shivering may also be encountered in the PACU following regional anesthesia.

Other causes of shivering should be excluded, such as sep-sis, drug allergy, or

a transfusion reaction. Intense shivering may increase oxygen consumption, CO2 production, and cardiac output. These

physiologi-cal effects are often poorly tolerated by patients with preexisting

cardiac or pulmonary impairment.

Postoperative shivering may increase oxygen consumption as much as

fivefold, may decrease arte-rial oxygen saturation, and may be associated with

an increased risk of myocardial ischemia. Although postoperative shivering can

be effectively treated with small intravenous doses of meperidine (12.5– 25 mg)

in adults, the better option is to reduce the likelihood of shivering by

maintaining normother-mia. Shivering in intubated and mechanically venti-lated

patients can also be controlled with sedation and a muscle relaxant until

normothermia is rees-tablished and the effects of anesthesia have dissipated.

Postoperative hypothermia should be treated

with a forced-air warming device, if available;alternately

(but less satisfactorily) warming lights or heating blankets can be used to

restore body temper-ature to normal. Hypothermia has been associated with an

increased incidence of myocardial ischemia, arrhythmias, increased transfusion

requirements, and increased duration of muscle relaxant effects, the latter of

which can be especially harmful in the recently extubated patient.

Related Topics