Chapter: Business Science : International Business Management : International Trade and Investment

Theories of International Trade & Investment

THEORIES OF INTERNATIONAL TRADE AND INVESTMENT:

Classical

theories

Contemporary theories Firm internationalization

FDI and Non-FDI explanations

Comparative advantage

Comparative

advantage is an economic theory about the potential gains from trade for

individuals, firms, or nations that arise from differences in their factor

endowments or technological progress. In an economic model, an agent has a

comparative advantage over another in producing a particular good if he can

produce that good at a lower relative opportunity cost or autarky price, i.e.

at a lower relative marginal cost prior to trade. The closely related law or

principle of comparative advantage holds that under free trade, an agent will

produce more of and consume less of a good for which he has a comparative

advantage.

David

Ricardo developed the classical theory of comparative advantage in 1817 to

explain why countries engage in international even when one country's workers

are more efficient at producing every single good than workers in other

countries. He demonstrated that if two countries capable of producing two

commodities engage in the free market, then each country will increase its

overall consumption by exporting the good for which it has a comparative

advantage while importing the other good, provided that there exist differences

in labor productivity between both countries.

Widely

regarded as one of the most powerful yet counter-intuitive insights in

economics, Ricardo's theory implies that comparative advantage rather than

absolute advantage is responsible for much of international trade

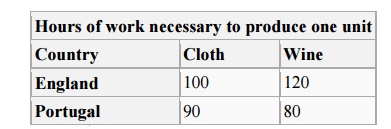

A famous

example, Ricardo considers a world economy consisting of two countries,

Portugaland England, which produce two goods of identical quality. In Portugal,

the a priori more efficient country, it is possible to produce wine and cloth

with l ess labor than it would take to produce the same quantities in England.

However, the relative c osts of producing those two goods differ between the

countries.

In order to produce an additional unit of cloth, England must commit 100 la bor hours, which could have instead produced 5/6 units of wine. Although Portugal can produce a unit of cloth with fewer hours of work (90 hours) than England, it must forego producing a greater amount of wine 9/8 (units) to do so. Accordingly , England is said to possess a comparative a dvantage in cloth even though Portugal possesses an absolute advantage in cloth. A similar argu ment would show that Portugal has both an absolute and comparative advantage in wine.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

In the absence of trade, England requires 220 hours of work to both produce a nd consume one unit each of cloth and wine while Portugal requires 170 hours of work to prod uce and consume the same quantities. If each country specializes in the good for which it ha s a comparative advantage, then the global produ ction of both goods increases, for England can spend 220 labor hours to produce 2.2 units of cloth while Portugal can spend 170 hours to produ ce 2.125 units of wine. Moreover, if both countries specialize in the above manner and England trades a unit of its cloth for 5/6 to 9/8 units of Portuga l's wine, then both countries can consume at least a unit each of cloth and wine, with 0 to 0.2 units of cloth and 0 to 0.125 units of wine re maining in each respective country to be consum ed or exported. Consequently, both England and Portugal can consume more wine and cloth un der free trade than in autarky.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

HECKSCHER–OHLIN MOD EL (H–O MODEL):

The

Heckscher–Ohlin m odel (H–O model) is a general equilibrium mat hematical model

of international trade, developed by Eli Heckscher and Bertil Ohlin at the

Stockholm School of Economics. It builds on David R icardo's theory of

comparative advantage by p redicting patterns of commerce and production b ased

on the factor endowments of a trading region. The model essentially says that

countries will export products that use their abundant and c heap factor(s) of

production and import products t hat use the countries' scarce factors.

2×2×2 MODEL

The

original H–O model assumed that the only difference between countries was the

relative abundances of labor and capital. The original Heckscher–Ohlin model

contained two countries, and had two commodities that could be produced. Since

there are two (homogeneous) factors of production this model is sometimes

called the "2×2×2 model".

The model

has "variable factor proportions" between countries—highly developed

countries have a comparatively high capital-to-labor ratio compared to

developing countries. This makes the developed country capital-abundant

relative to the developing country and the developing nation labor-abundant in

relation to the developed country.

With this

single difference, Ohlin was able to discuss the new mechanism of comparative

advantage, using just two goods and two technologies to produce them. One

technology would be a capital-intensive industry, the other a labor-intensive

business

theoretical

Assumptions.

Both countries have identical production

technology:

This

assumption means that producing the same output of either commodity could be

done with the same level of capital and labor in either country. Actually, it

would be inefficient to use the same balance in either country (because of the

relative availability of either input factor) but, in principle this would be

possible. Another way of saying this is that the per-capita productivity is the

same in both countries in the same technology with identical amounts of

capital.

Countries

have natural advantages in the production of various commodities in relation to

one another, so this is an "unrealistic" simplification designed to

highlight the effect of variable factors. This meant that the original H-O

model produced an alternative explanation for free trade to Ricardo's, rather

than a complementary one; in reality, both effects may occur due to differences

in technology and factor abundances.

In

addition to natural advantages in the production of one sort of output over

another (wine vs. rice, say) the infrastructure, education, culture, and

"know-how" of countries differ so dramatically that the idea of

identical technologies is a theoretical notion. Ohlin said that the H-O model was

a long-run model, and that the conditions of industrial production are

"everywhere the same" in the long run.

Production output is assumed to exhibit constant

returns to scale

In a

simple model, both countries produce two commodities. Each commodity in turn is

made using two factors of production. The production of each commodity requires

input from both factors of production capital (K) and labor (L). The

technologies of each commodity are assumed to exhibit constant returns to scale

(CRS). CRS technologies imply that when inputs of both capital and labor are

multiplied by a factor of k, the output also multiplies by a factor of k. For

example, if both capital and labor inputs are doubled, output of the

commodities doubled. In other terms production function of both commodities is

"homogeneous of degree 1".

The

assumption of constant returns to scale CRS is useful because it exhibits

diminishing returns in a factor. Under constant returns to scale, doubling both

capital and labor leads to a doubling of the output. Since outputs are

increasing in both factors of production, doubling capital while holding labor

constant leads to less than doubling of an output. Diminishing returns to

capital and diminishing returns to labor are crucial to the Stolper–Samuelson

theorem.

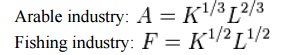

The technologies used to produce the two

commodities differ

The CRS

production functions must differ to make trade worthwhile in this model. For

instance if the functions are Cobb–Douglas technologies the parameters applied

to the inputs must vary. An example would be:

Where A

is the output in arable production, F is the output in fish production, and K,

L are capital and labor in both cases.

In this

example, the marginal return to an extra unit of capital is higher in the

fishing industry, assuming units of fish (F) and arable output (A) have equal

value. The more capital-abundant country may gain by developing its fishing

fleet at the expense of its arable farms. Conversely, the workers available in

the relatively labor-abundant country can be employed relatively more

efficiently in arable farming.

Factor mobility within countries

Within

countries, capital and labor can be reinvested and reemployed in order to

produce different outputs. Similar to Ricardo's comparative advantage argument,

this is assumed to happen without cost. If the two production technologies are

the arable industry and the fishing industry it is assumed that farmers can

shift to work as fishermen with no cost and vice versa.

It is

further assumed that capital can shift easily into either technology, so that

the industrial mix can change without adjustment costs between the two types of

production. For instance, if the two industries are farming and fishing it is

assumed that farms can be sold to pay for the construction of fishing boats

with no transaction costs.

The

theory by Avsar has offered much criticism to this.

Factor immobility between countries

The basic

Heckscher–Ohlin model depends upon the relative availability of capital and

labor differing internationally, but if capital can be freely invested anywhere

competition (for investment) will make relative abundances identical throughout

the world. Essentially, free trade in capital would provide a single worldwide

investment pool.

Differences

in labour abundance would not produce a difference in relative factor abundance

(in relation to mobile capital) because the labour/capital ratio would be

identical everywhere. (A large country would receive twice as much investment

as a small one, for instance, maximizing capitalist's return on investment).

As

capital controls are reduced, the modern world has begun to look a lot less

like the world modelled by Heckscher and Ohlin. It has been argued that capital

mobility undermines the case for free trade itself, see: Capital mobility and

comparative advantage Free trade critique.

Capital

is mobile when:

There are

limited exchange controls

Foreign

direct investment (FDI) is permitted between countries, or foreigners are

permitted

to invest in the commercial operations of a country through a stock or

corporate bond market

Like

capital, labor movements are not permitted in the Heckscher–Ohlin world, since

this would drive an equalization of relative abundances of the two production

factors, just as in the case of capital immobility. This condition is more

defensible as a description of the modern world than the assumption that

capital is confined to a single country.

Commodity prices are the same everywhere

The 2x2x2

model originally placed no barriers to trade, had no tariffs, and no exchange

controls (capital was immobile, but repatriation of foreign sales was

costless). It was also free of transportation costs between the countries, or

any other savings that would favor procuring a local supply.

If the

two countries have separate currencies, this does not affect the model in any

way purchasing power parity applies. Since there are no transaction costs or

currency issues the law of one price applies to both commodities, and consumers

in either country pay exactly the same price for either good.

In

Ohlin's day this assumption was a fairly neutral simplification, but economic

changes and econometric research since the 1950s have shown that the local

prices of goods tend to be correlated with incomes when both are converted at

money prices (although this is less true with traded commodities). See: Penn

effect.

Related Topics