Chapter: Forensic Medicine: Introduction

The inquest

The inquest

The Inquests Act provides, inter alia, for

``holding of inquests in cases of deaths or alleged deaths apparently occurring

from other than natural causes, and for matters incidental thereto ...''

How does the inquest court come to know of an alleged non-natural death?

Where a medical practitioner is unable to

certify that the death of his patient (or other person) was solely and

exclusively due to natural causes, he isThis section is based on Smith (1986)

and Strauss (1991:424).required to inform a policeman accordingly. In such

cases the doctor does not issue a death certificate. The police will inform a

magistrate accordingly, who will request the police to investigate the matter.

The police will then report to the public prosecutor.

The Act reads:

Any person [this includes the doctor or nurse]

who has reason to believe that ... a person has died ... due to other than

natural causes shall report accordingly to a policeman, unless he has reason to

believe that a report has or will be made by any other person.

Any policeman who has reason to believe that any

person had died ... from other than a natural cause shall investigate the

circumstances of the death or alleged death.

How does the medical practitioner become involved in the medical investigation of death?

The magistrate to whom the death is reported

must, if he deems it expedient in the interests of justice, cause it to be

examined by a medical practitioner (eg a forensic pathologist) ``who may, if he

deems it necessary for the purpose of ascertaining with greater certainty the cause

of death make or cause to be made an examination of any internal organ, or any

part or any contents of the body, or any other substance or thing''. For the

purpose of this examination ``any part or internal organ or contents of a body

may be removed'' and ``removed to any place''.

If the pathologist or any medical practitioner

has been involved in the treatment of the deceased before death, it is the

policy of the Department of Health that he should advise the magistrate

accordingly so that he can seek the assistance of another pathologist or

medical practitioner in order to conduct the post-mortem examination. In

practice he will generally consult with the forensic consultant, in other words

the chief pathologist for the region.

The post-mortem examination

The extent and nature of the post-mortem

examination is not prescribed by statute, but the medical practitioner

undertaking this task would be well advised to follow with discretion the

procedure as laid out in the report form provided for this purpose.

Who may be present at the post-mortem examination?

A police officer or another medical practitioner

nominated by any person, who satisfies the magistrate that he has a

``substantial and peculiar interest in the issue of the examination may be

present at the post-mortem examination, as well as any other person permitted

by the magistrate or the medical practitioner conducting the post-mortem

examination''. The attendance of students is included in the latter provision.

The doctor performing the autopsy should welcome the presence of a colleague,

who may be appointed by the relatives to represent their interests, as he

should have nothing to hide, and a second opinion is generally helpful (Strauss

1991:424).

Report of the examination

The findings at an autopsy, which are recorded

as the autopsy is done, are generally later transcribed on the prescribed form,

with (it is hoped) meticulous attention to relevant factual detail and

accuracy; these findings represent the personal factual observations of the medical

practitioner performing the examination (Nel 1986:5).

Subsequent proceedings and findings

The report is submitted to the investigating

police officer in the form of an affidavit. Together with the other relevant

documents it is submitted to the public prosecutor, who may call for additional

information. If criminal proceedings are not instituted, the prosecutor will

submit the documents and other information to the magistrate.

In terms of the Inquests Act the judicial

officer shall record a finding on the following:

·

the identity of the deceased

·

the date or likely date of death

·

the cause or likely cause of death

·

whether the death was brought about by any act or omission involving or

amounting prima facie to an offence on the part of any person

If the judicial officer is unable to record any

such finding she shall record that fact. It should be appreciated that the

evidence which justifies a finding of a likely cause of death may not stand the

test of a criminal trial or a civil action.

Both competent medical acts and omissions may

result in a death (eg death during a heart transplant operation or following

failure to institute specific treatment in a case of cerebral haemorrhage), but

such an act or omission need not constitute an offence in the sense of criminal

negligence.

If the body has been destroyed (eg by cremation)

or if no body can be recovered (eg in a sea disaster) and if the evidence

proves beyond reasonable doubt that the person has died, the judicial officer

shall accordingly record a finding of death and then proceed to make a finding

as in the case of all inquests.

At the termination of the inquest the judicial

officer is required to submit the record to the Director of Public Prosecution

in the following circumstances:

·

if she cannot make a finding

·

if she makes a finding that death was brought about by an act or

omission involving or amounting to an offence

·

if the Director of Public Prosecutions has requested that this be done

The Director of Public Prosecutions has the

powers to re-open an inquest or to permit exhumation of a body for further

investigation.

How do the findings affect the medical practitioner?

Trust not the physician

His antidotes are poison,

and he slays more than you rob.

(Shakespeare: Timon of Athens)

One may often have heard the above. However ...

``we cannot freely and wisely choose the right way for ourselves unless we know

both good and evil'' (Helen Keller).

If the finding in any way reflects adversely on

a medical practitioner, criminal and/or civil action or a disciplinary inquiry

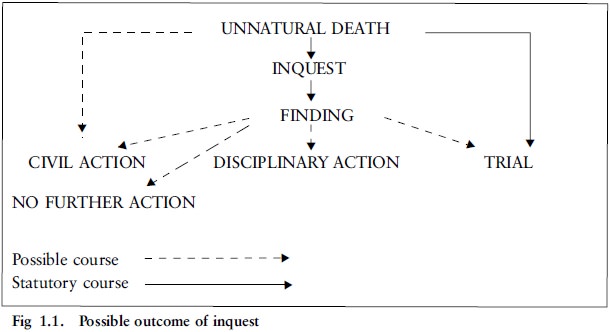

by the Health Professions Council of South Africa may ensue (fig 1.1).

An inquest can often help to identify the

medical ``good and evil'' because not infrequently it has a major medical component

which may reveal or conversely justify apparent medical shortcomings, and so

play an important role as an external audit of the quality of medical care.

Consequently the events leading up to inquests, the evidence and procedure, the

findings and the possible consequences arising from the findings should be of

interest to medical practice in its broadest sense, and should not be

restricted only to the forensic medical practitioner.

It is important that people develop a knowledge

of and interest in medical jurisprudence, particularly in the light of the

disturbing world-wide trends towards litigation against doctors and hospitals,

and also because patients are (rightly so) becoming more aware of what can

legitimately be expected as ``reasonably competent'' attention in the various

categories of medical medicine.

General reasons for censure of the medical practitioner at an inquest

The major cause for censure of the medical

practitioner can be summed up in the words ``failure to ...''. This may either

be the failure to institute acceptable treatment of the patient, or failure to

adhere to ethical norms.

The following questions need to be asked by the

doctor preparing to give evidence on a particular form of treatment:

·

Was the drug or procedure the correct choice, and was I competent to

administer it?

·

Was there a clear indication for its use?

·

Was I aware of dangers involved and contra-indications?

·

Did I attempt to anticipate by generally acceptable methods the

possibility that the patient might exhibit any idiosyncrasy to such use

·

Was I in a position to skilfully apply the necessary counteractants?

·

Was I in a position to skilfully manage any complications due to

intervention?

Related Topics