Anti-Colonial Movements and the Birth of Nationalism | India - The Great Rebellion of 1857 | 10th Social Science : History : Chapter 7 : Anti-Colonial Movements and the Birth of Nationalism

Chapter: 10th Social Science : History : Chapter 7 : Anti-Colonial Movements and the Birth of Nationalism

The Great Rebellion of 1857

The Great Rebellion of 1857

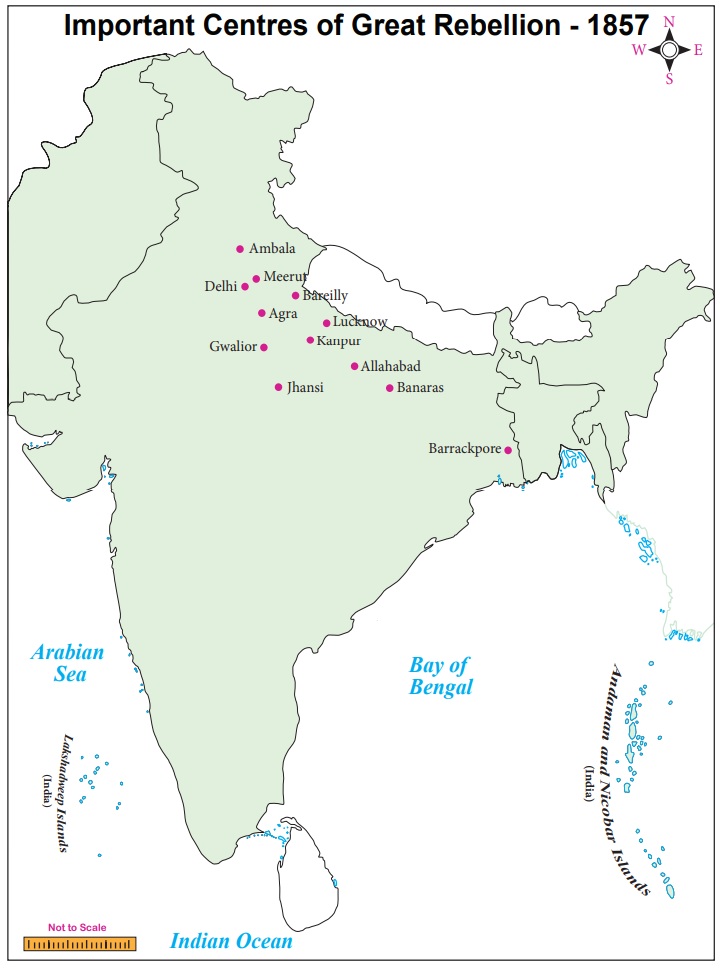

In 1857,

British rule witnessed the biggest challenge to its existence. Initially, it

began as a mutiny of Bengal presidency sepoys but later expanded to the other

parts of India involving a large number of civilians, especially peasants. The

events of 1857ŌĆō58 are significant for the following reasons:

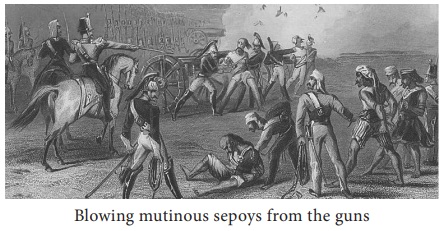

1. This was the first major revolt of armed forces

accompanied by civilian rebellion.

2. The revolt witnessed unprecedented violence,

perpetrated by both sides.

3. The

revolt ended the role of the East India Company and the governance of the

Indian subcontinent was taken over by the British Crown.

(a) Causes

i. Annexation Policy of British India

In the

1840s and 1850s, more territories were annexed through two major policies:

The Doctrine of Paramountcy. British claimed themselves as paramount,

exercising supreme authority. New territories were annexed on the grounds that

the native rulers were inept.

The Doctrine of Lapse. If a

native ruler did not have male heir to

the throne, the territory was to ŌĆślapseŌĆÖ into British India upon the death of

the ruler. Satara, Sambalpur, parts of the Punjab, Jhansi and Nagpur were

annexed by the British through the Doctrine of Lapse.

ii. Insensitivity to Indian Cultural Sentiments

In 1806

the sepoys at Vellore mutinied against the new dress code, which prohibited

Indians from wearing religious marks on their foreheads and having whiskers on

their chin, while proposing to replace their turbans with a round hat. It was

feared that the dress code was part of their effort to convert soldiers to

Christianity.

Similarly,

in 1824, the sepoys at Barrackpur near Calcutta refused to go to Burma by sea,

since crossing the sea meant the loss of their caste.

The

sepoys were also upset with discrimination in salary and promotion. Indian

sepoys were paid much less than their European counterparts. They felt

humiliated and racially abused by their seniors.

(b) The Revolt

The

precursor to the revolt was the circulation of rumors about the cartridges of

the new Enfield rifle. There was strong suspicion that the new cartridges had

been greased with cow and pig fat. The cartridge had to be bitten off before

loading (pork is forbidden to the Muslims and the cow is sacred to a large

section of Hindus).

On 29

March a sepoy named Mangal Pandey assaulted his European officer. His fellow

soldiers refused to arrest him when ordered to do so. Mangal Pandey along with

others were court-martialled and hanged. This only fuelled the anger and in the

following days there were increasing incidents of disobedience. Burning and

arson were reported from the army cantonments in Ambala, Lucknow, and Meerut.

Bahadur Shah Proclaimed as Emperor of Hindustan

On 11 may

1857 a band of sepoys from Meerut marched to the Red Fort in Delhi.

The

sepoys were followed by an equally exuberant crowd who gathered to ask the

Mughal Emperor Bahadur Shah II to become their leader. After much hesitation he

accepted the offer and was proclaimed as the Shahenshah-e-Hindustan (the

Emperor of Hindustan). Soon the rebels captured the north-western province and

Awadh. As the news of the fall of Delhi reached the Ganges valley, cantonment

after cantonment mutinied till, by the beginning of June, British rule in North

India, except in Punjab and Bengal, had disappeared.

Civil Rebellion

The

mutiny was equally supported by an aggrieved rural society of north India.

Sepoys working in the British army were in fact peasants in uniform. They were

equally affected by the restructuring of the revenue administration. The sepoy

revolt and the subsequent civil rebellion in various parts of India had a

deep-rooted connection with rural mass. The first civil rebellion broke out in

parts of the North-Western provinces and Oudh. These were the two regions from

which the sepoys were predominately

recruited. A large number of

Zamindars and Taluqdars were also attracted to the rebellions as they had lost

their various privileges under the British government. The talukdarŌĆōpeasant

collective was a common effort to recover what they had lost. Similarly,

artisans and handicrafts persons were equally affected by the dethroning of

rulers of many Indian states, who were a major source of patronage. The dumping

of British manufactures had ruined the Indian handicrafts and thrown thousands

of weavers out of employment. Collective anger against the British took the

form of a peopleŌĆÖs revolt.

Prominent Fighters against the British

The

mutiny provided a platform to aggrieved kings, nawabs, queens, and zamindars to

express the anti-British anger. Nana Sahib, the adopted son of the last Peshwa

Baji Rao II, provided leadership in he Kanpur region. He had been denied

pension by the Company. Similarly, Begum Hazrat Mahal in Lucknow and Khan Bahadur

in Bareilly took the command of their respective territories, which were once

ruled either by them or by their ancestors.

Another

such significant leader was Rani Lakshmi Bai, who assumed the leadership in

Jhansi. In her case Dalhousie, the Governor General of Bengal had refused her

request to adopt a son as her successor after her husband died and the kingdom

was annexed under the Doctrine of Lapse. Rani Lakshmi Bai battled the mighty

British Army until she was defeated.

Bahadur

Shah Jafar, Kunwar Singh, Khan Bahadur, Rani Lakshmi Bai and many others were

rebels against their will, compelled by the bravery of the sepoys who had

defied the British authority.

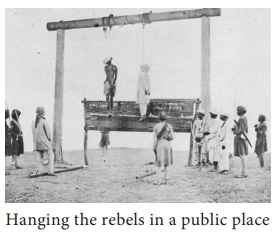

(c) Suppression of Rebellion

By the

beginning of June 1857, the Delhi, Meerut, Rohilkhand, Agra, Allahabad and

Banaras divisions of the army had been restored to British control and placed

under martial law.

(d) Causes of Failure

There is

hardly any evidence to prove that the rebellion of 1857 was organised and

planned. It was spontaneous. However, soon after the siege of Delhi, there was

an attempt to seek the support of the neighboring states. Besides a few Indian

states, there was a general lack of enthusiasm among the Indian princes to

participate in the rebellion. The Indian princes and zamindars either remained

loyal or were fearful of British power. Those involved in the rebellion were

left with either little or no sources of arms and ammunition. The emerging

English-educated middle class too did not support the rebellion.

One of

the important reasons for the failure of the rebellion was the absence of a

central authority. There was no common agenda that united the individuals and

the aspirations of the Indian princes and the various other feudal elements

fighting against the British.

In the

end, the rebellion was brutally suppressed by the British army. The rebel

leaders were defeated due to the lack of weapons, organisation, discipline, and

betrayal by their aides. Delhi was captured by the British troops in late 1857.

Bahadur Shah was captured and transported to Burma.

(e) India Becomes a Crown Colony

The

British Parliament adopted the Indian Government Act, in November 1858, and

India was pronounced as one of the many crown colonies to be directly governed

by the Parliament. The responsibility was given to a member of the cabinet,

designated as the Secretary of State for India.

Changes in the Administration

British

rule and its policies underwent a major overhaul after 1857. British followed a

cautious approach to the issue of social reform. Queen Victoria proclaimed to

the Indian people that the British would not interfere in traditional

institutions and religious matters. It was promised that Indians would be

absorbed in government services. Two significant changes were made to the

structure of the Indian army. The number of Indians was significantly reduced.

Indians were restrained from holding important ranks and position. The British

took control of the artillery and shifted their recruiting effort to regions and

communities that remained loyal during 1857. For instance, the British turned

away from Rajputs, Brahmins and North Indian Muslims and looked towards

non-Hindu groups like the Gorkhas, Sikhs,and Pathans. British also exploited

the caste, religious, linguistic and regional differences in the Indian society

through what came to be known as ŌĆ£Divide and RuleŌĆØ policy.

Related Topics