The Age of Revolutions | History - The French Revolution | 12th History : Chapter 11 : The Age of Revolutions

Chapter: 12th History : Chapter 11 : The Age of Revolutions

The French Revolution

The French Revolution

In the 18th century, Europe was ruled by monarchs

of various dynasties, and they wielded absolute powers. Along with the nobility

and clergy they enjoyed hereditary privileges. In France the clergy and

nobility did not pay taxes like the common people. It was in this context that

the French Revolution occurred and stood for liberty, equality, and fraternity.

France in Eighteenth Century

The political and social system of France prior to

the French Revolution was called ancien

regime, meaning old order. Under

the regime, everyone was a member of an estate. All rights and status flowed

from three orders namely clergy, nobility and others, belonging to the Third

Estate. France was ruled by Louis XVI, a young king of the Bourbon dynasty. He

was married to Mary Antoinette, the princess of Austria. The king had absolute

power and he led a lavish lifestyle. The government taxed the poor and not the

rich.

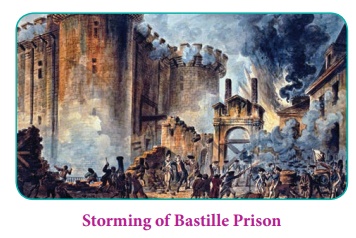

On 14 July 1789, the Paris mob, hungry due to a lack of food from poor harvests, upset at the conditions of their lives and annoyed with their king and government, stormed the Bastille fortress (a prison). The storming of the Bastille symbolised the beginning of a new age in the history of the world. There were many reasons for the outbreak of this revolution.

Conditions of Peasantry

The peasantry made up the bulk of French society.

The peasants were serfs. They had to work certain days in the week for their

lords without any remuneration. They could not marry or dispose of their lands

without the lord’s permission. Lords claimed certain feudal dues such as the

right to levy fees even for using ovens to bake bread, and a toll on sheep and

cattle possessed by the peasants. It has been estimated that the peasant paid

eighty percent of his earnings to various tax collectors. Carlyle wrote that

‘one third of them had nothing but third-rate potatoes to eat for one-third of

the year.’

Three Estates

French society had three main divisions or estates: Clergy (the priestly class),

Nobility (the landed and aristocratic class), and the rest, the commoners,

formed the unprivileged class. The clergy and the nobility enjoyed special

privileges and they were exempted from various taxes imposed by the monarchy.

Out of the three divisions, only the third estate bore the brunt of taxation,

as other two estates were exempted from tax payment due to the special

privileges. The important taxes were tithe,

a tax exclusively collected by the church on the laity, Taille, a tax paid by the peasants, gabelle salt tax, and tax on tobacco.

The peasants could not fight feudal regulations on

their own. They looked for outside help and leadership. The rising bourgeoisie

wanted their political power to match their economic status. They wanted to

have a voice in government. So the bourgeoisie took the lead and were

instrumental in bringing about the French Revolution.

The Bourgeoisie comprised the

educated middle class. Writers, doctors, teachers, lawyers, judges, and civil

servants formed this class.

Financial Bankruptcy

France was in constant war with neighbouring

British Empire that proved to be too costly for the exchequer. It had spent

enormous sums on the Seven Years’ War with Britain and Prussia, and more again

during the American war with Britain. The valuable assistance which the French

gave to the American colonists was such as it could not really afford. The

government had to pay high interests on the loan. In order to settles the dues,

the government imposed more taxes on the common people. The nobles and higher

clergy hesitated to come forward and save the state by voluntarily giving up

their claims to exemption from taxes. Matters were further complicated by the

extravagance of the court and the incompetence of the Louis XVI.

Role of Intellectuals

Long before the revolution of 1789 there was a

revolution in the realm of ideas. Public intellectuals (who were called philosophes in the French language) who

were inspired by the Enlightenment ideal of applying reason to all spheres of

knowledge played a key role in preparing the soil for the outbreak of the

French Revolution. The writings of Voltaire and Rousseau acted as an impetus to

the revolution. Montesquieu (1689–1755), in his The Spirit of Laws, argued for the division of power among the legislative, executive and judiciary and opposed

the concentration of power in a single hand. Voltaire (1694– 1778), in his The Age of Louis XIV, opposed the

religious superstitions of the French and criticised the French administration

under the rule of the monarchs. Rousseau (1712–1778), in his Social Contract, argued that the

relationship between the rulers and ruled should be bound by a contract. If the

ruler ruled the country in a just manner, he would be respected by his

subjects. If he ruled in an unjust manner, in violation of the contract, he

should be punished. The English philosopher, John Locke, in ‘Two Treatises of

Government’, opposed the divine right and absolute monarchy. These ideas were

also expressed in the writings of Diderot and the Encyclopaedists.

Rousseau is known for his famous

beginning lines of The Social Contract,

'Man is born free but everywhere he is in chains'.

The French Revolution

The Beginning

The French Revolution began with the meeting of the

Estates -General in May 1789. The summoning of the Estates-General became

necessary because of the financial problems faced by the government. The first

two estates, namely, the clergy and nobility had sent 300 representatives each

to the meeting held at the palace of Versailles, while the 600 delegates of the

third estate, mainly the business people and educated members, were made to

stand behind them. The question that was taken up at the Estates General was

how they would vote. According to the norm each estate had one vote and Louis

XVI wanted the same arrangement to continue. However, the third estate wanted

one vote for each member.

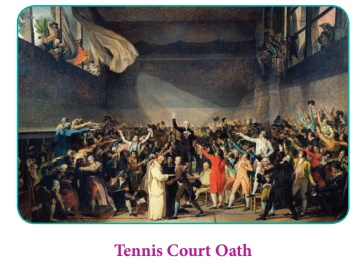

Tennis Court Oath

When this demand by the third estate was not

accepted, the representatives formed the National Assembly on 17 June 1789.

Then they left the Estates General and assembled at the tennis court on 20 June

1789. They took the ‘tennis court oath’ by which they wanted to limit the power

of the monarch and introduce a new constitution. In this protest, they were led

by a noble named Mirabeau and a clergy, Abbé Sieyès.

The Storming of the Bastille

When the representatives of the third estate were

busy with the formation of the national assembly, the common people were

suffering due to the high price of essential commodities, even as the rich

merchants started hoarding the grains. The agitated women started storming into

the market area. Seeing the unrest, the king ordered the army to move into the

streets of Paris. Angered by this move, the people stormed the Bastille, the

great prison of the city of Paris, and after destroying the fort released the

prisoners on 14 July 1789.

14 July is still celebrated as

Bastille Day or the French National Day in France.

National Assembly

The fall of Bastille emboldened the National

Assembly to abolish feudalism in the country. Shaken by the turn of events, the

king also accepted the formation of a national assembly. The Church was asked

to forego its privileges and abolish the tithe. In 1791, the National Assembly

drafted the constitution by which the powers of the king were limited. It also

proposed to have three different organs: executive, legislative and judiciary.

The members of the National Assembly were indirectly elected by a group of

electors. The electors were voted by the male citizens, who were above 25 years

of age and who paid taxes. Thus the majority of the citizens did not get voting

rights.

Constitution Making

The National Constituent Assembly prepared the

constitution. On 26 August 1789 the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the

Citizen was adopted. It subordinated the monarchy to the rule of law and

defined individual and collective rights. It maintained that no person shall be

accused, arrested or imprisoned except in those cases established by the law

(clause 7); and insisted that taxation could only be raised by common consent

(clause 14). Thomas Jefferson’s influence is clearly discernible in clause 1,

which declares that, ‘Men are born and remain free and equal in rights’.

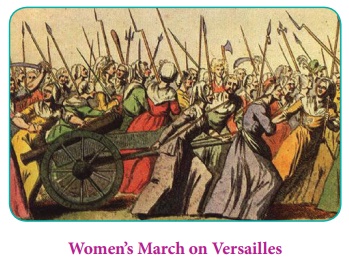

Women played a significant role in the French

revolution. Women from the poorer areas of Paris marched on Versailles

supported by 20,000 armed men. They broke into the palace and forced the king

to return with them to Paris, where he was kept under public surveillance. Many

women were politically active. Olympe de Gouges was dissatisfied with the

Declaration of Rights of Man and of the Citizen, as it excluded women. She

wrote the Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Citizen, arguing for

equality for women.

The Declaration of the Rights of Man

and of the Citizen has a preamble and 17 articles. The first article contains

the statement: “Men are born and remain free and equal in rights.” The purpose

of “political association,” as the Declaration states, should be the

preservation of these rights, detailed as liberty, security to property, and

resistance to oppression. It also declares that both sovereignty and law should

come from the “general will.” It protects the freedom of speech and of religion

and insists on equal treatment before the law. It also asserts that taxes should

be paid by all citizens in accordance with their means. The Declaration served

as the preamble to the Constitution of 1791.

War against Austria and Prussia

While the king agreed to the constitutional

monarchy on one hand, on the other he was secretly appealing for help from

Austria and Prussia. The neighbouring kingdoms were watching the developments

in France with concern. They feared that the rise of common people might bring

to an end the rule of monarchs and so they sent their troops to France to

contain the revolution. Meanwhile the National Assembly declared war against

Austria and Prussia. On hearing this, people from various parts of France

united to fight the foreign forces. A group of people from the place of

Marseilles proceeded to Paris by singing the Marseillaise song.

A song for French troops from

Marseilles composed (1792) by Roget de Lisle came to be called La Marseillaise. By a degree enacted on

14 July 1795, it was declared the national anthem of France

Formation of Clubs

The common people continued to suffer even after

the formation of the National Assembly. Majority of the people saw the assembly

as a place for rich persons as commoners were excluded from voting. The new

armed power in Paris was in the hands of a National Guard recruited from the

middle class. Lafayette, who acted as an official French adviser in the

American War of Independence, was its chief. There was a general feeling of

liberation and exaltation when the king, ex-aristocrats, the middle classes and

the Parisian masses jointly commemorated the first anniversary of the fall of

the Bastille as a great festival. But this sense of unity did not last long.

Dissatisfied people started forming political clubs to discuss the problems

they faced. One such club which attained popularity was the Jacobin Club in

Paris. The members were from poor sections of the society – small scale

business people, artisans, servants and wage labourers. Their leader was

Maximilian Robespierre. A majority of the members of the Jacobin club wore

long-striped trousers as against the trousers with knee breeches usually worn

by the noble class. In order to differentiate from them, they called themselves

‘the people without knee breaches’ (sans-culottes).

Another lawyer Danton dominated the Cordelier Club.

Girondins and Jacobins

Lafayette’s constitutional monarchy dominated the

political scene for two years. An attempt by the king to flee Paris in June

1791 to join counter-revolutionary armies congregating across the border was

thwarted by the local militia. Yet food shortages, price rises and unemployment

drove the artisans and traders as well as the labourers to the point of

despair. Repression could not stop rising popular upsurge. The moderates who

ran the government fell out among themselves. Within the Jacobin Club a group

called the Girondins, also known as the Brissotins (after one of their leaders,

Brissot), were less radical than Robespierre and Danton. Though there were

differences of opinion among themselves, all of them excepting Robespierre,

believed that a war against the foreign powers would help. Robespierre,

however, argued that war would open the door to counter-revolution. But he

could not stop the Girondins from agreeing with the king to form a government

and then declaring war on Austria and Prussia in April 1792.

National Convention

The plan of Girondins turned out to be a disaster.

The enraged members of the Jacobin Club stormed into the palace of Tuileries,

the official residence of Louis XVI, and ransacked it. They killed the guards

and took the king as prisoner. A new assembly called Convention voted that the

king should be imprisoned and a new election conducted to elect a leader for

the country. In this election, every one above the age of 21 got the right to

vote, without any distinction in wealth, and status.

September Massacres

After the overthrow of the monarchy, the people

believed that political prisoners in the jails were planning to join a plot of

the counter-revolutionaries. So the mob descended on the prisons and summarily

executed those they believed to be royalists. Commencing on 2 September 1792,

at Abbaye prison in Paris, it continued in the next four days in other prisons

of the city.

In all about 1,200 prisoners were killed in what

came to be known as the September Massacres. The September Massacres were

publicised abroad as proof of the horrors of revolution. The Girondins blamed

their more radical enemies, especially Marat, Danton and Robespierre.

Work of the National Convention

On 20 September 1792 the revolutionary army halted

the invading forces at Valmy. The next day the new Convention abolished

monarchy and declared France a republic.

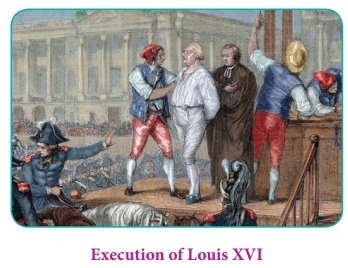

King Louis XVI was brought before the People’s

tribunal and executed by guillotine on 21 January 1793. The offence he

committed was his appeal to foreigners for help against his own people. Soon

afterwards Marie Antoinette was beheaded.

Against a background of growing hunger in the towns

and countryside alike, there were demands from the Parisians to control prices,

to maintain grain supplies to feed people and to take action against hoarders

and speculators. Instead of initiating steps to meet the just demands of the

Parisian masses, the Convention used the army to attack the agitating masses.

The army suffered a series of defeats as its commander deserted to the enemy.

Disillusioned peasants in the Vendee region in the west of France joined a

monarchist rising. Finally moderates and royalists (29 May 1793) together

seized control of Lyons, where silk industry was thriving and wealthy merchants

from Germany and Italy had settled.

Rule of Jacobins

Robespierre did not want to lose the gains made in

the previous four years and hence commenced his dictatorial rule. The Jacobins

sent Girondin leaders to the guillotine, a beheading machine. Danton was

beheaded.

The period between 1793 and 1794 was also a time of

radical reforms. On 4 February 1794 the Jacobin-dominated Convention decreed

the abolition of slavery in all French Lands. Robespierre imposed a maximum

ceiling on the wages of the people. Food items such as bread and meat were

rationed. Prices were fixed by the government for farm produces. The use of Sir

and Madam was replaced by the use of the words male citizen and female citizen.

Religious places such as churches were converted into army barracks. Angered

over the radicalisation of the government and at the base of society, his own

party members turned against Robespierre. He was convicted and finally executed

in 1794.

Dr Joseph-Ignace Guillotin was a

French physician, who in an article wrote about a machine to quickly execute

the convicts. Though he did not invent such a machine, it was named after him.

The invention is attributed to Antoine Louis.

The Directory

The allies who had overthrown Robespierre did not

stay long in power. Those who hated the revolution began to take over the

streets of Paris, attacking anyone who tried to defend the revolutionary

ideals. There were two risings in April and May 1795. But they were crushed by

forces loyal to the new political group called Thermidorians. Emigres began to return to the country

and boast that the monarchy would be restored soon.

Emigres: Persons who leave their own country in order to settle in another

for political reasons. In the present context, the nobles who fled France in

the years following the French Revolution came to be called émigrés.

In October 1795 the royalists staged a rising of

their own in Paris. The army led by a rising officer and one-time Jacobin named

Napoleon Bonaparte came to their assistance. Fearful of bloodshed, the

Thermidorians agreed to concentrate power in the hands of a Directory of five

men. In four years, under one pretext or another, Napoleon gained power. In 1799

Napoleon staged a coup which in effect gave him dictatorial power. In 1804

Napoleon made the Pope crown him as the Emperor of France.

The French revolutionaries may have been defeated,

but much of the revolution’s heritage survived to shape the modern world.

Impact of French Revolution

·

The French revolution created a deep impact, not

only in France but also all over Europe, and even inspired anti-colonial

intellectuals and movements across the world in the nineteenth and early

twentieth centuries.

·

The French revolution brought to an end the rule of

Louis XVI in France.

·

It reduced social inequality. The privileges given

to certain sections of the society based on birth were curtailed.

·

It introduced a republican form of government with

electoral rights.

·

The feudal system was abolished

·

Slavery was abolished though it took some more

years for the total abolition of slavery

·

The Church lost it supremacy and it became

subordinate to the state. Freedom of faith and religious tolerance had come to

stay.

·

The Declaration of Rights of Man and Citizens

brought to light the importance of personal and collective rights.

·

The three organs of the government, namely, the

legislative, executive and judiciary became

prominent, and kept a check and balance on each other. It removed the

concentration of power under a single authority.

·

All over Europe, the French Revolution gave the

hope to the people to end the despotic rule and establish an egalitarian

society

Related Topics