The Age of Revolutions | History - Revolution in Latin America | 12th History : Chapter 11 : The Age of Revolutions

Chapter: 12th History : Chapter 11 : The Age of Revolutions

Revolution in Latin America

Revolution in Latin America

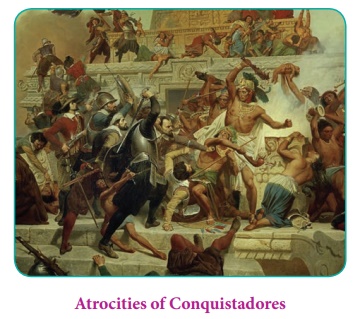

The regions of Latin America were conquered by the

Spanish in the sixteenth century. The Portuguese and the French also had their

presence there. The political power of the South American cultures such as the

Incas and the Aztecs was destroyed by these colonial powers. The colonizers (conquistadores) brought to an end the

local religious beliefs and introduced Catholic religion. The colonial rule in

Latin America was brutal and was marked by widespread genocide and decimation

of the indigenous population. The native people were made to work as slave

labourers in the farm lands as well as the mines of the colonial masters who

exported goods such as sugar, coffee, gold and silver to European nations.

Latin America today consists of many nations such

as Mexico, Brazil, Argentina, Peru, Chile, Venezuela, and Caribbean countries

in Central and South America.

The Haitian Revolution

Haiti, earlier known as Saint-Domingue (as the

French called their colony) was the richest French colony (1659–1804) in the

Caribbean Sea. Its plantations produced more sugar than all of Europe’s other

Caribbean and American colonies put together. The island’s indigenous

population, forced to mine for gold, was devastated by European diseases and

brutal working conditions, and by the end of the sixteenth century it had

virtually vanished. Landowners in western Hispaniola imported increasing

numbers of African slaves. By 1789, the estimated 556,000 population of

Saint-Domingue included 500,000 African slaves, 32,000 European colonists

(whites), and 24,000 free affranchis or

mulattoes (black-people of mixed African and European descent).

News of the storming of the Bastille was followed

by armed defiance of the royal governor. Vincent Ogé, a mulatto, who had

lobbied with the Parisian assembly for colonial reforms, led an uprising in

late 1790 but was captured and executed. In May 1791 the French revolutionary

government granted citizenship to the wealthier mulattoes who had even owned

slaves. But Haiti’s European population disregarded the law. Within two months

isolated fighting broke out between European whites and mulattoes. All of them

expected the black slaves to continue working, suffering and dying as if

nothing had changed. But they took them by surprise when in August thousands of

slaves rose in rebellion.

The European whites attempted to appease the

mulattoes to quell the slave revolt. The French National Assembly granted

citizenship to all mulattoes in April 1792. The country was torn by rival

factions, some of which were playing into the hands of Spanish colonists in

Santo Domingo or of British troops from Jamaica. In 1793, a commissioner,

Léger-Félicité Sonthonax, was sent from France to maintain order. He offered

freedom to slaves who joined his army. He soon abolished slavery altogether, a

decision ratified subsequently by the French government.

In the late 1790s, Toussaint L’Ouverture, a

military leader and former slave, gained control of several areas. Napoleon

sent a fleet of 12,000 troops to seize control of Saint-Domingue from Toussaint

L’Ouverture’s forces. The war which followed was prolonged and bloody. At one

point the French army seemed to have won after Toussaint was misled into

believing in the possibility of conciliating with the enemy. But he was kidnapped

and killed. His former lieutenant Dessalines rose to the occasion and organised

black resistance. He defeated Napoleon’s army. Saint Domingue became the

independent black state of Haiti in 1804.

Venezuela and New Granada (now Columbia)

Inspired by the Haitian revolution, slaves in

Venezuela rose in rebellion in the 1790s. Creoles (persons of mixed European

and black descent) wanted an expansion of the free trade that was benefiting

their plantation economy. At the same time, however, they feared that the

removal of Spanish control might bring about a revolution that would destroy

their own power. Therefore, they formed the strong loyalist faction in the

Viceroyalty of New Granada.

In 1808 Napoleon had made his brother Joseph the

king of Spain after the abdication of the weak king Charles IV in favour of his

son Ferdinand. Napoleon had them both imprisoned. With Charles and Ferdinand

removed from the scene, the Empire was without a stable government for six

years. The political crisis in Spain provided the opportunity for the assertion

of its colonies. Soon the rebels as patriots organised revolutionary

governments that introduced some social and economic reforms in 1810.

In Venezuela

the patriots led by Simon Bolivar openly declared a break with Spain the following

year. The earthquake that wreaked particular destruction in patriot-held areas

in 1812 provided the pretext for loyalist forces to crush the patriots’ army,

and drive Bolivar and others to seek refuge in New Granada (the heart of the

viceroyalty).

Bolívar soon returned to Venezuela with a new army

in 1813 and waged a campaign with the army’s motto, “Guerra a muerte” (“War to

the death”). The army led by loyalist Jose Tomas Boves again succeeded in

driving Bolívar out of his home country. By 1815 independence movements in

Venezuela and almost all across Spanish South America seemed dead. A large

military expedition sent by Ferdinand VII in that year re-conquered Venezuela

and most of New Granada. Yet another invasion led by Bolívar in 1816 failed.

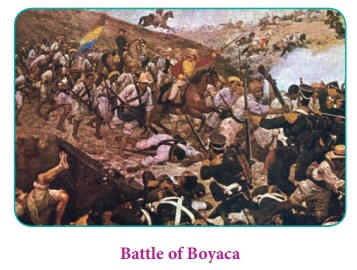

The following year (1817) a larger and revitalised

independence movement emerged, winning the struggle in the north and taking it

into the Andean highlands. Bolivar emerged as a strong military and political

force after the struggles. At this point a group of llaneros (cow boys) of mixed ethnicity led by Jose Antonia Paez

joined the struggle and contributed decisively to the patriots’ military

victories in 1818–19. After leading his army up the face of the eastern Andes,

Bolívar dealt a crushing defeat to his enemies in the Battle of Boyaca.

Consolidating victory in the north proved

difficult. A congress that Bolívar convened in Angostura in 1819 named Bolivar

as president of Gran Colombia, a union of what are today Venezuela, Colombia,

Panama, and Ecuador. But the sharp divisions prevailing in the region

ultimately dashed Bolívar’s hopes of uniting the former Spanish colonies into a

single new nation as United States of Latin America. Furthermore, loyalist

supporters still held much of Venezuela, parts of the Colombian Andes, and all

of Ecuador. Conditions became favourable in 1820 troops waiting in Cádiz to be

sent as part of the crown’s military campaigns revolted. Eventually New Granada

and Venezuela were liberated in 1821. A congress held that year in Cúcuta, a

Columbian city, chose Bolívar president of a now much more centralised Gran

Colombia.

Simon Bolivar: Bolivar belonged to

an old aristocratic Creole family in

Caracas. He was of fundamental importance to the movement as an ideologue and

military leader. In his most famous “Jamaica Letter” (written during one of his

periods of exile, 1815), Bolívar affirmed his undying faith in the cause of

independence, even in the face of the patriots’ repeated defeats. While

critiquing Spanish colonialism, Bolívar held the view that the only path for

the former colonies was the establishment of an autonomous and centralised

republican government. The type of republic that he eventually espoused was

very much an oligarchic one. He believed that a virtuous governing system would

not be possible if the nation was divided by ethnicity. Bolivar was an

inspiring figure to left-wing and emancipatory movements in Latin America even

in the latter half of the twentieth century.

Mexican Revolution

The independence of Mexico came late. Mexico had a

powerful segment of Creoles and Peninsulars, who were the colonial masters born

in Spain or Portugal. For many of the powerful in Mexican society, a break with

Spain meant a loss of traditional status and power. Between 1808 and 1810,

Peninsulars had acted aggressively to preserve Spain’s power in the region.

Rejecting the notion of a congress that would address the question of

governance in the absence of the Spanish king, leading Peninsulars in Mexico

City deposed the viceroy and persecuted Creoles. They then welcomed weaker

viceroys whom they knew they could dominate. Peninsulars’ efforts could not,

however, prevent the emergence of an independence struggle.

The revolution in Mexico was led by a catholic

priest, Miguel Hidalgo. He supported the poor people of Mexico and sympathised

with the poor living conditions of Native Americans. His emotional speeches at

the Church of Dolores called for independent Mexico. He led a revolutionary

army consisting of Mestizos against the army of Spain and Creoles. However, he

was defeated and killed in 1811. Later the movement was led by Jose Maria

Morelos, who declared independence from Spain in 1813. He was also defeated in

1815.

The Creoles or the wealthy merchants were watching

the developments in Spain where a movement to overthrow monarchy and to make a

new constitution was afoot. Thinking that this might reduce the power of the

Creoles, they declared independence in 1821. It is interesting to note that the

person who led the movement was the same officer who defeated the army of Maria

Morelos. He declared himself as the emperor whose ruthless rule was overthrown

finally. In 1824 Mexico declared itself as a republic.

Independence of Brazil

Brazil was a colony of Portugal. When Napoleon

invaded Portugal in 1808, the Portuguese emperor Dam Joao (John VI) fled to

Brazil. He had developed the colony in all aspects by introducing land reforms

and establishing military, medical and art schools. Even after the defeat of

Napoleon, the Portuguese ruler continued to stay in Brazil. But when his power

was challenged he decided to go to Portugal leaving the colony of Brazil in the

hands of his son Dom Pedro.

The reliance of the Brazilian upper classes on African

slavery favoured their continued ties with Portugal. Plantation owners depended

on the African slave trade, which Portugal controlled. The size of the slave population

– approximately half the total of Brazilian population in 1800 – also meant

that Creoles shied away from political initiatives that might mean a loss of

control over their social inferiors. Therefore, the Portuguese authorities at

home put an end to the reforms undertaken by Joao in Brazil. They wanted Dom

Pedro to return to Portugal. However, Pedro declared Brazil’s independence and

decided to stay on. In 1822, Brazil obtained independence from Portugal and it

became the only constitutional monarchy in South America with Pedro I becoming

its first emperor.

Other Revolts

The liberator of Argentina, San Martin joined the

Chilean liberator Bernardo O’Higgins and both were able to get independence for

Chile in 1818 followed by Peru in 1820. Bolivar and San Martin met at the port

in Ecuador, Guayaquil, to discuss the future course of actions in Latin America

and for a probable unification. While San Martin wanted European form of

government with constitutional monarchy in the colonies, Bolivar wanted

republican form of government. Though they could not reach any agreement, San

Martin retired and allowed Bolivar to take full command. Bolivar could get

independence for all South American colonies by 1826.

After the independence of all the colonies, Bolivar

tried to unite all Latin American countries under one nation called Gran

Colombia. However, the rugged geographical features with mountains and forests

along with power struggles could not make it a reality. Though most of the

Latin American countries declared themselves as republics and were free from

Spanish rule, they were still dependent to a greater extent on foreign powers.

While Mexico was invaded by the US and France, in the course of the nineteenth

century, Britain continued to exercise its dominating influence over countries

like Argentina and Chile for a long time to come. In each Latin American

country oligarchic cliques ran rival Liberal and Conservative parties and

preserved unequal social structure characterised by extreme privilege to great

landowners and grinding poverty to the underprivileged.

In the twentieth century, especially after World

War II, South America was a troubled continent as USA sought to control it by

pliant dictatorial governments (often referred to as banana republics).

Related Topics