by Satyajit Ray | Prose - The Attic | 10th English: UNIT 4 : Prose: The Attic

Chapter: 10th English: UNIT 4 : Prose: The Attic

The Attic

Prose

The Attic

Satyajit Ray

It is natural for human beings to make mistakes. When we realise

our mistakes, we should try to rectify them. If you get a chance to rectify

your mistake or pay back for it......... what would you do and how would you

correct it?

Aditya and I were returning from the site of our new factory at

Deodarganj. We were driving along National Highway 40. We had reached a point

where the road bifurcated . If we drove ten kilometres along the road that branched off to the right,

we would reach Bramhapur. I asked Aditya whether he was interested in

revisiting the place of his birth, which he had left after he had passed the

matriculation examination from the local school to continue his studies in

Calcutta.

‘When I left our ancestral house, twenty-nine years ago, the house

was almost two hundred years old,’ recollected Aditya. ‘I doubt if even the

school building, which may have undergone many changes, will be recognisable

any more. Trying to revive old childhood memories may prove disappointing!’

But he said he wished to visit the tea shop of Nagen Uncle, if it

still existed, and have a cup of tea there.

So we took the turning to the right and decided to drive to

Bramhapur, of which Aditya’s ancestors were once the zamindars.

a. When did Aditya leave the local school?

b. Why did Aditya think that the school would not be

recognisable?

Aditya’s father had left the ancestral home and moved to Kolkata,

where he had set up his own business. After his death, Aditya was looking after

it, and I was his friend and business partner.

It was the month of Magha, that is January – February by the

English calendar – the middle of winter. By my watch, it was 3:30 in the

afternoon. The sun was soothing. On either side of the road were paddy fields, as far as the eye

could see. Harvest was over and there had been a good crop that year.

After about ten minutes, we came to the local school. Beyond the

iron gates were the playing field and the two-storeyed school building. We got

down from the car and stood in front of the gate.

c. Who were Aditya’s ancestors?

d. How was the landscape through which they travelled.

e. What did Aditya visit?

I asked Aditya whether everything was still the same. He replied

that everything had changed.

‘Our school used to be one-storeyed, and a new building has come

up, which wasn’t there.’

‘Were you not a good student?’ I asked.

‘Yes, but my position was always second,’ he replied. We decided

to go and have tea at Nagen uncle’s tea shop, which stood next to a grocery

shop and opposite a temple dedicated to Lord Shiva. Soon, we caught sight of

‘Nagen’s Tea Cabin’ written on a signboard over the shop.

The owner of the tea shop, now over sixty, a little rustic in appearance, with his

white neatly-combed hair and clean look, was the same as before. He was wearing

a dhoti and a blue striped shirt that could be seen from under a green shawl.

Not recognising Aditya, he asked us where we had come from.

‘Deodarganj,’ Aditya replied. ‘We are on our way to Kolkata.’

A little surprised, Nagen uncle asked why we were there.

‘To have tea at your shop, ’ said Aditya. ‘Certainly, besides tea,

I have biscuits and savouries.’

‘Give us two nankhatai each.’.

f. Where was nagen uncle’s shop?

g. Besides tea, what did Nagen uncle have in his shop?

We sat on two tin chairs. There was only one other customer

sitting at a corner table, neither eating nor drinking tea, but sitting with

his head bent, as though he were sleeping.

Addressing him as Mr Sanyal, Nagen uncle reminded him to go home,

as it was already 4 p.m. Other customers would soon be coming. Addressing us he

said, with a wink in his eye, ‘A little hard of hearing. Cannot see well

either. But has no money to buy spectacles.’

From his reaction to this speech, I began to wonder whether Mr

Sanyal was not a little crazy as well, because suddenly he stood up, stretched

himself and, raising his lean right arm, and with eyes dilated, began to recite a poem

by Tagore – Panraksha (‘Keeping of a Promise’). Having recited the poem, he

left the place, making the gesture of Namaste with his hands, to nobody in

particular.

h. What did Nagen uncle tell about Sanyal?

g. In what way was Mr. Sanyal’s behaviour strange?

I noticed a sudden change in Aditya’s expression and I asked him

the reason for it. Without answering me, he asked Nagen uncle who the gentleman

was and what he did.

Nagen uncle replied, ‘Sasanka Sanyal. What can be done? He leads a

cursed life – gone crazy, I think, but has not forgotten any incident of the

past. Sold his lands to get his only daughter married. He lost his wife and

only son last year. Since then he is somewhat changed – not really normal.’

‘Where does he stay?’

‘He stays with a friend of his father’s – Jogesh Kabiraj. Sasanka

comes here, has tea and biscuits and always remembers to pay – having an acute

sense of self-respect. But how long things will remain like this, I don’t

know’.

j. What did Nagen uncle tell

about Sanyal’s past life?

k. How did Sanyal show that he had a sense of self-respect?

Having paid our bill and ascertained the location of Jogesh Kabiraj’s house, we got

into the car. Aditya was at the wheel. He expressed the wish to visit his

house.

‘So you do want to see your house after all?’ I said.

‘It has become essential to do so,’ Aditya replied. His nerves

seemed overwrought for some

reason. We soon reached the house, which was surrounded by high walls. Even

from the ruins, one could easily imagine how grand it must have been once upon

a time.

We entered the building, climbed up the stairs and reached the

attic on the second floor of the house.

‘This was my favourite room,’ said Aditya. The attic has always been a

favourite with children. It is in the attic that the child seems to be in a

world of its own.

A portion of a wall of the attic had crumbled down, and through the

‘window’ that had been created,

we could see the sky, the fields, a part of the rice mill, the spire of the old temple. In

the whole house, the attic had probably been the worst hit by wind and weather. The

floor was strewn with twigs and straw and pigeon droppings. Among other things,

there was a broken cricket bat, the remains of an armchair and a wooden packing

case.

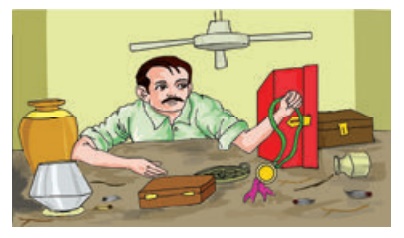

Aditya got on top of the packing case and pushed his hand inside

the ventilator, thus upsetting a sparrow’s nest, a part of which fell to the

ground. However, he heaved a sigh of relief when he had got what he had been

looking for. When I asked him what it was, he said, ‘You’ll get to know very

soon.’

l. Why was the attic ‘a favourite place’ for the children?

m. What did Aditya do on reaching the attic?

We next went to a jeweller’s to find out the weight of the

article. The jeweller remarked that it was an antique. Our next stop was the

house of Jogesh Kabiraj. Though I was a little curious, I didn’t ask Aditya

anything.

We entered the house and went to the room where Sasanka Sanyal

stayed. Sasanka uncle was busy reciting verses from Tagore. When he had

finished, Aditya asked, ‘May we come in?’ He turned and faced us.

‘No one visits me,’ he said in an unperturbed manner.

‘Would you mind if we come in?’ ‘Come in.’

Except for a charpoy there was nothing else to sit on, so

we remained standing.

‘Do you remember Aditya Narayan Chowdhury?’ Aditya asked him.

‘Of course,’ said the gentleman. ‘’The spoilt child of affluent parents! Was a fairly

good student but could never beat me. He was extremely jealous of me. And he

used to tell lies.’

‘I know,’ said Aditya. He then took out a packet from his pocket

and handing it over to him, said, ‘This is for you, from Aditya.’

n. What did the jeweller say about the article?

o. Was Sanyal happy about his visitors?

‘What is it?’ he asked.

‘Money’.

‘Money?How much money?’

‘One hundred and fifty rupees. He has said that he will be happy

if you accept it.’

‘Shall I laugh or cry? Aditya has given me money! Why this sudden

generosity?’

‘Man does change with time. Perhaps Aditya is not the same Aditya

as before?’

‘A change? I got the prize. He could not bear it. He took it from

me to show his father and never returned it to me. Said that there was a hole

in his pocket and it had fallen through it.’

‘This is the price of the medal. It is yours.’

Sasanka Sanyal was amazed. He stared at Aditya and said, ‘The

price of the medal? That could not be more than five rupees. It was a silver medal.’

‘Silver is now thirty times costlier than before.’

‘Really? I had no news of that. But …’

Sasanka uncle looked at the fifteen ten-rupee notes in his hand

and then looked at Aditya. There was a completely new expression on his face.

He said, ‘Aditya, this smacks too much of charity. Doesn’t it?’

We remained silent. Peering intently at Aditya, Sasanka Sanyal

smiled and said, ‘I had recognised you at Nagen uncle’s tea shop by that

mole on your right cheek. I could see you had not recognised me. So I recited

the same poem that I had recited on the prize-giving day, on purpose, so that

you may remember. Then, when you came to visit me, I couldn’t help venting my

anger on you.’

‘You have done the right thing. Your grievances are absolutely

justified. But I will be happy if you accept the money,’ said Aditya.

Sasanka Sanyal shook his head and said, ‘No. Money will soon be

spent. I would have preferred to have the medal if it were possible. I would

have forgotten that unpleasant incident of my childhood if I could get the

medal back.’

So, the medal that had been hidden in the attic for twenty-nine

long years was eventually restored to its owner.

‘Sriman Sasanka Sanyal – Special Prize for Recitation - 1948’ was

still clearly engraved on it (Translated from the Bengali story

Chilekotha)

p. Why did Sanyal recite the poem in the tea shop earlier?

q. What was engraved on the medal?

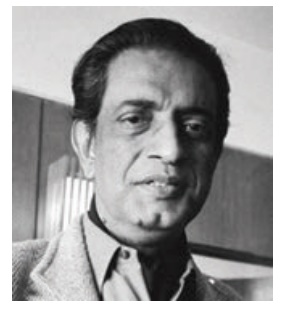

About the Author:

Satyajit Ray (1921 - 1992) was an Indian

film maker, screen writer, graphic artist, music composer and author. He

was born in Kolkatta. He authored several short stories and novels meant

primarily for young children and teenagers. He revived the children’s magazine

‘Sandesh’ (which his grandfather had started in 1913) and edited it until his

death in 1992. Ray was more interested in writing, rather than film making. His

stories have been translated in Europe, the United States and many other

countries. Ray received many awards including 32 national film awards by the

Government of India, notably the Padma Bhushan in 1965 and the highest civilian

honour ‘Bharat Ratna’ shortly before his death.

Related Topics