Chapter: Clinical Dermatology: Physical forms of treatment

Surgery - Physical forms of treatment

Physical forms of treatment

The

skin can be treated in many ways, including surgery, freezing, burning,

ultraviolet radiation and lasers. Some broad principles will be discussed here.

Surgery

As

our population ages, and becomes more concerned about appearances, requests for

skin surgery are becoming more common. The distinction between traditional

dermatological surgery and cosmetic sur-gery is blurring. There are few over

the age of 50 years who do not have a benign tumour that they consider unsightly and wish to have

removed. There are also many who are unhappy with a skin damaged by cumulative

sun exposure, or concerned about medically trivial abnormalities on their face.

To term the treatment of all these as ‘cosmetic’ seems harsh. Health care

systems cannot cover the cost of treating all such problems but family doctors

and dermatologists should be able to discuss with their patients any recent

developments in photo-therapy, laser treatment and specialized surgery that might

help them. For example, doctors should be able to explain that diode lasers can

remove unwanted hair permamently and without visible scarring, and the pros and

cons of such treatment as well as supply-ing the names of specialists expert in

it.

Skin biopsy

The

indications for biopsy, and the techniques employed, are described in Earily.

Excision

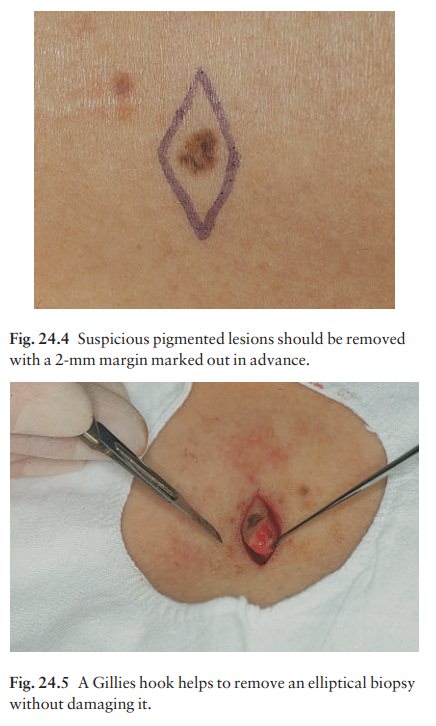

Excision

under local anaesthetic, using an aseptic technique, is a common way of

removing small

After injection of the local anaesthetic [usually 1 or 2% lignocaine

(lidocaine) with or without 1 in 200 000 adrenaline (epinephrine);], the lesion

is excised as an ellipse with a margin of normal skin, the width of which

varies with the nature of the lesion and the site (Fig. 24.4). The scalpel

should be held perpendicular to the skin surface and the incision should reach

the subcutaneous fat. The ellipse of skin is carefully removed with the help of

a skin hook (Fig. 24.5) or fine-toothed forceps. Larger wounds, and those where

the scar is likely to stretch (e.g. on the back), are closed in layers with

absorbable sutures (e.g. Dexon) before apposing the skin edges without tension

using non-absorbable interrupted or continu-ous subcuticular sutures such as nylon

or Prolene. Stitches are removed from the face in 4–5 days and from the trunk

and limbs in 7–14 days. Artificial sutures (e.g. Steri-Strip) may be used to

take the tension off the wound edges after the stitches have been taken out.

Shave excision

Many

small lesions are removed by shaving them off at their bases with a scalpel

under local anaesthesia. This procedure is suitable only for exophytic tumours

that are believed to be benign. Some cells at the base may be left and these,

in the case of malignant tumours, would lead to recurrence.

Saucerization excision

This modified shave excision extends into the sub-cutaneous fat. It is used to remove certain small skin cancers and worrying melanocytic naevi. It leaves more scarring than a shave excision but the technique provides tissue that allows the dermatopathologist to determine if a tumour is invading and to measure tumour thickness if the lesion is a melanoma. Further-more, the technique may ensure complete removal more adequately than shave excision.

Curettage

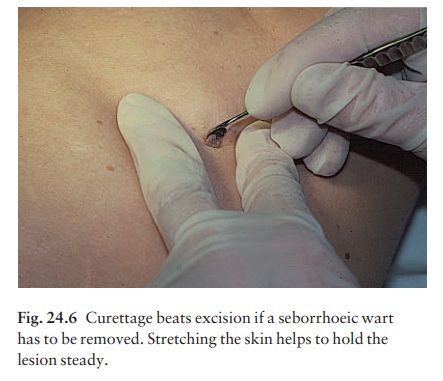

Curettage

under local anaesthetic is also used to treat benign exophytic lesions (e.g.

seborrhoeic keratoses; Fig. 24.6) and, combined with electrodesiccation , to

treat some basal cell carcinomas. Its main advantage over purely destructive

treatment is that histological examination can be carried out on the curettings.

A sharp curette is used to scrape off the lesion and haemostasis is achieved by

local haema-tinics, by electrocautery or electrodesiccation. The wound heals by

secondary intention over 2–3 weeks, with good cosmetic results in most cases.

When

a basal cell carcinoma is treated, the curette is scraped firmly and thoroughly

along the sides and bottom of the tumour (the surrounding dermis is tougher and

more resistant to curettage than the carcinoma) and the bleeding wound bed is

then elec-trodesiccated aggressively. This stops bleeding and destroys a zone

of tissue under and around the excised tumour to provide a tumour-free margin.

The process is repeated once or twice at the same session to ensure that all of

the tumour has been removed or destroyed. Only small basal cell carcinomas

outside the skin folds should be treated in this way. The recurrence rates are

relatively high for tumours in the nasolabial folds, over the inner canthi and

on the nose, glabella and lips. The technique should not ordinarily be usedfor

sclerosing basal cell carcinomas, invasive lesions larger than 1–2 cm, rapidly

growing tumours or for those with micronodular features on histology.

Microscopically controlled excision (Mohs’ surgery)

This

form of surgery for malignant skin tumours is time-consuming and expensive, but

the probability of cure is greater than with excision or curettage. First, the

tumour is removed with a narrow margin. The excised specimen is then marked at

the edges, mapped and, after rapid histological processing, is immediately

examined in horizontal and vertical section. If the tumour extends to any

margin, further tissue is removed from the appropriate place, based on the

markings and mappings, and again checked histologically. This process is

repeated until clearance has been proved histologically at all margins. The

resulting wound can then be closed directly, covered with a split skin graft or

allowed to heal by secondary intention.

Mohs’

surgery is useful to treat:

•

a basal cell carcinoma with a poorly

defined edge;

•

a sclerosing basal cell carcinoma

(can suggest an enlarging scar clinically);

•

a recurrent basal cell carcinoma;

•

a basal cell carcinoma lying where

excessive mar-gins of skin cannot be sacrificed to achieve complete removal of

the tumour (e.g. one near the eye);

•

basal cell carcinomas in areas with

a high incidence of recurrence such as the nose, glabella or nasolabial folds;

•

some squamous cell carcinomas; and

•

occasional malignant tumours other

than basal and squamous cell carcinomas.

Flaps and grafts

These

can be used to reconstruct a defect left by the wide excision of a tumour, or

when a tumour is removed at a difficult site, e.g. the eyelid or tip of the

nose.

Electrosurgery

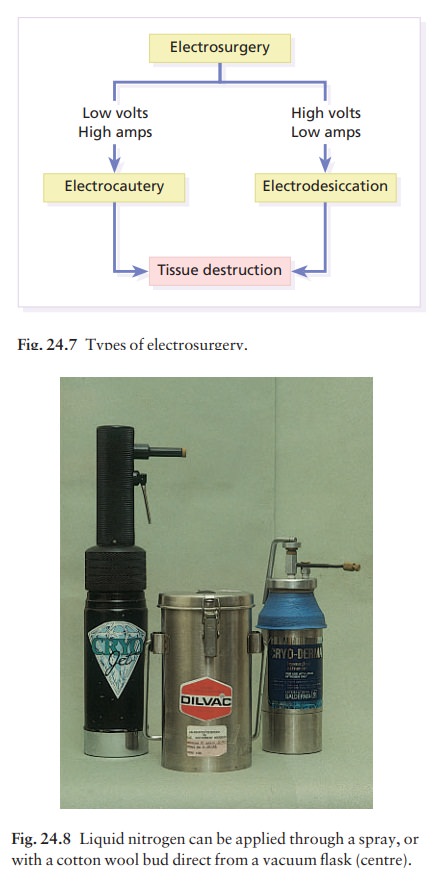

This

is often combined with curettage, under local anaesthesia, to treat skin tumours.

The main types are shown in Fig. 24.7.

Related Topics