Chapter: Medical Microbiology: An Introduction to Infectious Diseases: Introduction to Pathogenic Parasites: Pathogenesis and Chemotherapy of Parasitic Diseases

Significance of Human Parasitic Infections

SIGNIFICANCE OF HUMAN PARASITIC INFECTIONS

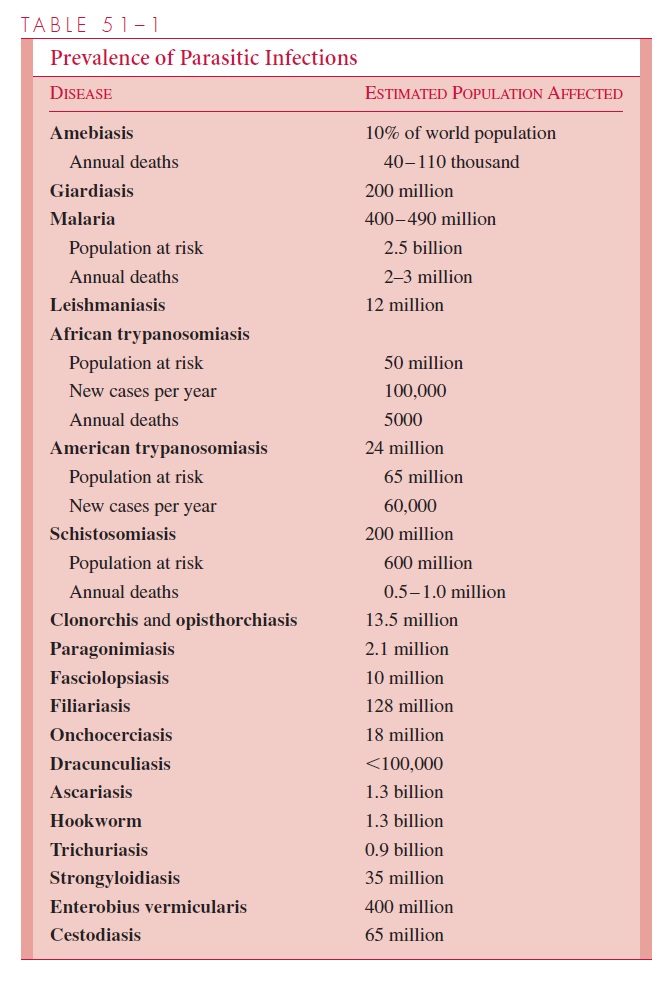

The relative infrequency of parasitic infections in the temperate, highly sanitated societies of the industrialized world has sometimes led to the parochial view that knowledge of parasitology has little relevance for physicians practicing in these areas. The continuing presence of parasitic disease among the impoverished, immunocompromised, sexually active, and peripatetic segments of industrialized populations, however, means that most physicians will regularly encounter those pathogens. Parasitic diseases remain among the major causes of human misery and death in the world today and, as such, are important obstacles to the development of the economically less favored nations (Table 51–1).

Moreover, a number of recent medical, socioeconomic, and political phenomena have combined to produce a dramatic recrudescence of several parasitic diseases with impor-tant consequences to both the United States and the developing world.

Currently, 2.5 billion people live in malarious areas, and of these, approximately 500 million are infected at any given time. Between 1 and 3 million people, predominately children, die of malaria each year. Plasmodium falciparum, the most deadly of the malar-ial organisms, has developed resistance to several categories of antimalarial agents, and resistant strains are now found throughout Southeast Asia, parts of the Indian subconti-nent, southeast China, large areas of tropical America, and tropical Africa. Growing resis-tance of the mosquito vector of malaria to the less toxic and less expensive insecticides has resulted in a cutback of many malaria control programs. In countries such as India, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka, where eradication efforts had previously interrupted parasite transmission, the disease incidence has increased 100-fold in recent years. In tropical Africa, the intensity of transmission defies current control measures. Of direct interest to American physicians is the spillover of this phenomenon to the United States. Presently, approximately 1000 cases of imported malaria are reported annually.

Entamoeba spp. are intestinal protozoa that infect 10% of the world’s population, in-cluding 2 to 3% in the United States. The majority of individuals are infected with the noninvasive E. dispar. The invasive E. histolytica produces amebiasis, a disease character-ized by intestinal ulcers and liver abscesses. It is more commonly seen in the poorly sani-tated areas of the world, but occurs in the United States as well, particularly in institutions for the mentally retarded and among migrant workers and some male homosexuals.

In the poor, rural areas of Latin America, Trypanosoma cruzi infects an estimated 16 million individuals annually, leaving many with the characteristic heart and gastroin-testinal lesions of Chagas’ disease. In Africa, from the Sahara Desert in the north to the Kalahari in the south, a related organism, Trypanosoma brucei, causes one of the most lethal of human infections, sleeping sickness. Animal strains of this same organism limit food supplies by making the raising of cattle economically unfeasible.

Leishmaniasis, a disease produced by another intracellular protozoan, is found in parts of Europe, Asia, Africa, and Latin America. Clinical manifestations range from a self-limiting skin ulcer, known as oriental sore, through the mutilating mucocutaneous infec-tion of espundia, to a highly lethal infection of the reticuloendothelial system (kala azar).

In 1947 Stoll, in an article entitled “This Wormy World,” estimated that between the tropics of Cancer and Capricorn there were many more intestinal worm infections than peo-ple. The prevalence was judged to be far lower in temperate climates. Warren, however, re-cently estimated that 27% of the American population harbored worms. The most serious of the helminthic diseases, schistosomiasis, affects an estimated 200 million individuals in Africa, Asia, and the Americas. Individuals with heavy worm levels develop bladder, intesti-nal, and liver disease, which may ultimately result in death. Unfortunately, the disease is frequently spread as a consequence of rural development schemes. Irrigation projects in Egypt, the Sudan, Ghana, and Nigeria have significantly increased the incidence of the dis-ease in these areas, often mitigating the economic gains of the development program itself.

Two closely related filarial worms, Wuchereria bancrofti and Brugia malayi, which are endemic in Asia and Africa, interfere with the flow of lymph and can produce grotesque swellings of the legs, arms, and genitals. Another filaria produces onchocercia-sis (river blindness) in millions of Africans and Americans, leaving thousands blind.

Toxoplasmosis, giardiasis, trichomoniasis, and pinworm infections are four cos-mopolitan parasitic infections well known to American physicians. The first, a protozoan infection of cats, infects possibly one third of the world’s human population. Although it is usually asymptomatic, infection acquired in utero may result in abortion, stillbirth, pre-maturity, or severe neurologic defects in the newborn. Asymptomatic infection acquired either before or after birth may subsequently produce visual impairment. Immunosup-pressive therapy may reactivate latent infections, producing severe encephalitis.

Related Topics