Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Neurosurgery for Treatment Refractory Psychiatric Disorders

Risks of Neurosurgical Intervention

Risks

of Neurosurgical Intervention

Surgical Risks

Surgical

risks include acute and subacute complications like he-morrhage, postoperative

infections and seizures, as well as more serious enduring side effects such as

focal neurological deficits, cognitive or personality change and weight gain.

Neuropsychiatric Risks

Cognitive/Intellectual Domain

With

regard to cingulotomy, an independent study of a cohort of patients was

performed for the US government by the Department of Psychology at the

Massachusetts Institute of Technology. The authors reported that they found no

evidence of lasting neurological, intellectual, personality, or behavioral

deficits after surgery (Corkin et al.,

1979; Corkin, 1980). In fact, a comparison of preoperative and postoperative

scores revealed modest gains in the Wechsler IQ ratings. The only apparent

irreversible decrement identified by these investigators was a decrease in

performance on the Taylor Complex Figure Test in patients older than age 40

years. Several authors, using varying assessment strategies and batteries pre

and postoperatively, have reported the relative lack of serious adverse

cognitive effects following cingulotomy (Corkin et al., 1979; Corkin, 1980), subcaudate tractotomy (Bartlett and

Bridges, 1977; Göktepe et al., 1975),

limbic leukotomy (Mitchell-Heggs et al.,

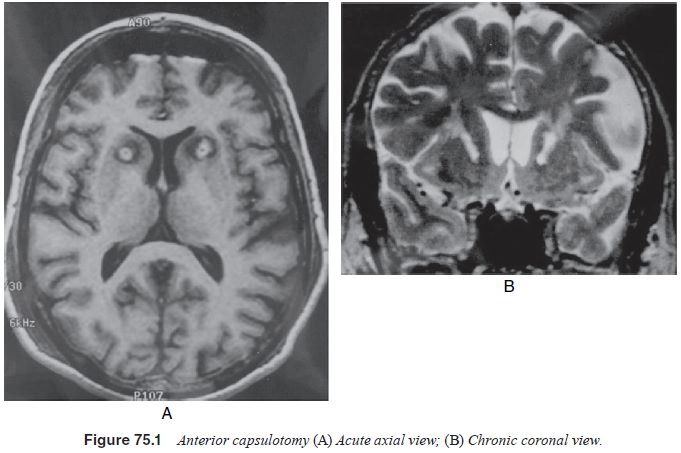

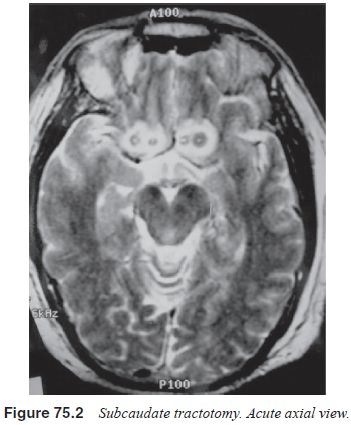

1976; Kelly, 1980) and capsulotomy (Herner, 1961; Bingley et al., 1977; Vasko and Kullberg, 1979) (Figures 75.1 and 75.2).

Nevertheless, the need to include carefully thought out (based on the procedure

involved) neurocognitive assessments before and at regular intervals after the

surgery/surgeries cannot be overstated. Long-term studies are desirable for the

existing procedures better to inform patients and clinicians of the risks as

well to help rehabilitative efforts.

Affective/Social and Personality Domains

As these neurosurgical procedures may be expected to influence, directly or indirectly, frontal lobe and other functions compris-ing one’s “personality”, it is important that this is an integral part of the pre and postoperative assessment. Important domains that need to be addressed are executive functions, impulsivity/aggres-siveness, social propriety and mood changes. Ideally this would involve input from both the patient as well as the family and treat-ing clinician. In general, anecdotal evidence from most reported studies concerning the different procedures suggest a remarkable freedom from significant adverse personality changes. On the contrary, the few studies that have directly addressed this issue re-port an improvement in negative personality traits at follow-up.

One of

the better researched instruments is the Karolinska Scales of Personality

(KSP), developed by Schalling and coworkers (1987). The KSP contains subscales

measuring traits related to frontal lobe function as well as those reflecting

anxiety proneness. In capsulotomy studies reported from Sweden, the KSP was

administered to 24 consecutive patients 1 year and 8 years after radiofrequency

capsulotomy. Small changes in mean scores towards normalization were apparent

on all 15 KSP subscales at the 1-year follow-up and significant improvement was

reported in anxiety proneness at the 8-year follow-up (Mindus et al., 1999).

One would

expect that the more precise modern surgical procedures should further reduce

this risk. In fact most recent studies report a low incidence of adverse

behaviors postsurgery. However, this remains a potential risk and conclusions

based on observations made on groups of patients may not preclude nega-tive

adverse effects in an individual patient.

Suicide

While

suicide is not considered a known complication of neuro-surgical procedures in

nonpsychiatric patients undergoing these procedures, the possibility of

contributing directly or indirectly to this process in psychiatric patients is

theoretically present. However, it is important to note that severe major

depression is associated with high lifetime suicide rates (approximately 3–8%)

(Nierenberg et al., 2001). Thus, of

the suicides reported in psy-chiatric neurosurgical cohorts, it is difficult to

ascertain whether these are a result of existing psychopathology or whether the

surgery contributed in some way to this process.

For example, Jenike and colleagues (1991) found that four of 33 patients who had undergone cingulotomy for OCD had died by suicide at follow-up that averaged 13 years. Chart reviews revealed that each of these suicide completers had been noted to suffer from extensive comorbid disease (especially severe depression) with prominent suicidal ruminations at initial evaluation for cingulotomy. On the contrary, none of the OCD patients without baseline suicidality became suicidal after the operation. In the large (n 5 44) prospective long-term follow-up study following one or more cingulotomies, Dougherty and colleagues (2002) reported one suicide (2%) in a patient having severe depression with chronic suicidal ideation and a past history of a suicide attempt. Thus, in most published studies, the suicide rate has been low and these patients have been noted to have had significant presurgical suicidality. This highlights the need carefully to assess for and monitor suicidality in this severely ill population.

Patients

with a poor response to surgery may be at increased risk for suicide (Jenike et al., 1991). Preventative strategies

there-fore include careful assessment of suicidality at baseline and

fol-low-ups, assessment of family and clinician support networks, clear explanations

of the scope of the procedure as well as the long response latency (usually a

year for cingulotomy), education that presurgical nonresponders sometimes

respond to treatment postsurgery, and the need for secondary or tertiary

lesions in case of cingulotomy in some patients to achieve response.

Related Topics