Europe in Turmoil | History - Rise of Socialist Ideas and Birth of Communism | 12th History : Chapter 12 : Europe in Turmoil

Chapter: 12th History : Chapter 12 : Europe in Turmoil

Rise of Socialist Ideas and Birth of Communism

Rise of Socialist Ideas and Birth of Communism

Socialist ideas in the modern sense came to be

articulated by the Physiocrats or the economists who were making enquiries into

the production and distribution of food and goods. Étienne-Gabriel Morally, the

Utopian thinker, in his Code de la Nature

(1755), denounced the institution of private property and proposed a

communistic organisation of society. He was the precursor of various schools of

collectivist thinkers in the nineteenth century who are categorised as

Socialists. Francois Babeuf, a political agitator of the French Revolutionary

period, felt that the Revolution in France did not address the needs of the

peasants and workers, and argued in favour of abolition of private property and

for common ownership of land.

Utopian Socialism

The earliest socialists in Europe were not

revolutionaries. They proposed idealistic schemes for cooperative societies, in

which all would work at their assigned tasks and share the outcome of their

common efforts. The term “Utopian Socialism” was first used by Karl Marx and

Friedrich Engels to describe the ideas articulated by the socialists before

them. Utopian Socialists recommended the establishment of model communities,

where the means of production would be collectively owned. They promoted a

visionary idea of a socialistic society, devoid of poverty or unemployment.

Their influence led to the establishment of several hundred model communes

(communities) in Europe and USA. Claude- Henri Saint -Simon,

Francois-Marie-Charles Fourier and Robert Owen were some of the prominent

Utopian Socialists.

Claude Henri Saint-Simon (1760–1825)

Saint Simon was a French aristocrat who fought

against the British in the American War of Independence. A strong believer in

science and progress, he criticised contemporary French society for being in

the grip of feudalism. Saint-Simon suggested that scientists take the place of

priests in the social order. He expressed the view that property owners who

held political power could hope to maintain themselves against the propertyless

only by subsidising the advance of knowledge. In his book called New Christianity he advocated the

adoption of the Christian principle of concern for the poor.

Charles Fourier (1772–1837)

Fourier was An early Utopian Socialist. He believed

that social conditions were the primary cause of human misery. Social and economic

inequality could be overcome if everybody had the basic minimum. Fourier

believed in the goodness of human nature and rejected the dogma of “original

sin”. He saw harmony as the law of the cosmos and held that what is true for

nature must be true for society. He envisaged a harmonious self-contained

co-operative society called phalansteres.

It was a community where there would be equal distribution of profit and loss.

Robert Owen (1771–1858)

Among the factory owners of Manchester there was a

humanitarian by name Robert Owen. Shocked by the condition of the factory

workers, he introduced many reforms in his own factories and improved the

condition of the workers. He did not employ children below the age of 10 in his

industries. Later he criticised private property and profit. He began to

advocate the new establishment of cooperative communities that would combine

industrial and agricultural production. In his book A New View of Society (1818),

he advocated a national education

system, public works for the unemployed and reform of the Poor Laws. Thanks to

his efforts, the British Parliament passed the Factory Act of 1819. By the

mid-1820s Owen had developed a theory of Utopian Socialism based on social

equality and cooperation. His other initiatives included formation of the Grand

National Consolidated Trades Union (1834) and the Cooperative Congresses

(1831-1835).

Poor Laws: In Britain the Poor Laws, as codified (1597–98) during Elizabethan

period, provided relief for the aged, sick, and infant poor, as well as work

for the able-bodied unemployed in workhouses.

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (1809–1865)

Proudhon was a French anarchist who contributed

significantly to the development of socialism. Unlike the earlier Utopian

socialists who were drawn from the middle class, he belonged to the working

class. Drawing inspiration from the cooperative communities, he and other

anarchists were opposed to the state and believed in revolution. In his

pamphlet titled “What is Property?” he wrote that “All property is theft.”

Proudhon believed that labour should be the basis for social organisation and

that all systems of government were oppressive. He wanted to replace

nation-state with federations of autonomous communes. In 1848-49, he was a

member of the National Assembly but was disillusioned by his experience. His

ideas became popular among the working class of France by the middle of the

nineteenth century. In 1864, some of the followers of Proudhon issued the

Manifesto of the Sixty. The manifesto declared that the French Revolution of

1789 only brought about political equality and not economic equality. They

wanted the working class to be represented by themselves. In the 1863

elections, they unsuccessfully sponsored three working class candidates in the

parliamentary elections of France. His views, which influenced the Russian

anarchist thinker Michael Alexandrovich Bakunin, sought to overthrow the state

by a general strike and replace it with democratically-run cooperative groups.

Anarchism: Belief in the abolition of state and organisation of society on a

voluntary, cooperative basis without recourse to force or compulsion

Louis Jean Joseph Charles Blanc (1811-1882)

An influential French socialist, Louis Blanc, in

1839, started the Revue du Progres,a journal of advanced social thought. His most

important essay “Organisation of Labour” serially appeared in 1839. In his

writings, he proposed a scheme of state-financed but worker-controlled “social

workshops” that would guarantee work for everyone and lead gradually to a

socialist society. Louis Blanc argued that socialism cannot be achieved without

state power. In 1848, he became a member of the French provisional government

and was able to influence it to set up workshops for the unemployed and provide

employment to all who needed it.

Karl Marx and Scientific Socialism

Karl Marx (1818–1883) and Friedrich Engels

(1820–1895) made the most profound contribution to socialism. Eventually their

ideas came to be known as Marxism or Communism. They called their views on

socialism as scientific socialism. On the eve of the 1848 Revolution, Marx and

Engels published The Communist Manifesto. The most famous rallying cry

in this famous work is: “Workers of

the world, unite! You have nothing to lose but your chains.”

Marx believed that in just the same way as

capitalism replaced feudalism, so socialism would eventually replace

capitalism. Marx built his theory on a belief that there is a conflict of

interests in the social order between the prosperous employing classes of

people and the employed mass. With the advance in education, this great

employed mass will become more and more class-conscious and more and more firm

in their antagonism to the class-conscious ruling minority. In some way the

class-conscious workers would seize power, he prophesied, and inaugurate a new

social state.

In 1867 Marx published the first volume of Das Kapital, a critique of capitalism.

In this work, he highlighted the exploitation of the proletariat (the working

class) by the bourgeoisie (the capitalist class).

The International Working Men’s Association,

founded in 1864, was influenced by his ideas. Its purpose was to form an

international working class alliance. Marx worked hard to exclude the moderates

from the International and denounced other socialists such as Ferdinand

Lassalle and Bakunin. Despite his efforts to consolidate the International it

declined by 1876. However, many socialist parties emerged in Europe: the German

Social Democratic Party in 1875, the Belgian Socialist Party in 1879, the Paris

Commune, 1871 and the establishment of a socialist party in 1905. The Second

International was founded in Paris in 1889 which influenced the socialist

movement till the outbreak of the First World War.

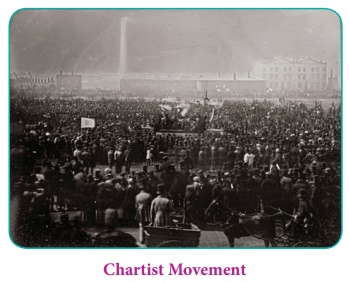

Chartism in England

In England the working class lined up behind the

Chartist movement. The Chartist movement was not a riot or revolt. It was an

organised movement. The impact of 1830 French Revolution in England was the

outbreak of militant labour agitation. Different streams of agitation converged

to give rise to the Chartist movement. The chartists propagated their ideas

through newspapers such as The Poor Man’s

Guardian, The Charter, The Northern Star and The Chartist Circular. Its principal

paper, the Northern Star, founded in

1837, soon equalled the circulation

of the Times. Articles published in

the Northern Star were read out for

the illiterates in workshops and pubs in every industrial area.

Hundreds of thousands of workers attended mass

meetings held The during1838–39. People's Charter, prepared by William Lovett

of the London Working Men’s Association, detailing the six key points that the

Chartists believed were necessary to reform the electoral system, was presented

and deliberated in these meetings. The six key points were:

·

Universal suffrage.

·

Voting by ballot, to prevent intimidation.

·

No property qualification for candidates.

·

Payment of members elected to the House of Commons,

as it would enable the poor people to contend for office and contest elections.

·

Equal electoral districts and equal representation.

·

Annual parliaments.

Panicked by rumours that there would be a popular uprising, the government sent the army to the industrial areas. In 1842 the workers struck work in Lancashire and marched from factory to factory stopping the work, and extending and intensifying their action. In 1848, in the wake of a wave of revolutions that swept Europe, subsequent to the February Revolution of that year in France, masses of workers prepared again for confrontation. The state stood firm with the backing of the lower middle class. The Chartist leaders also vacillated, when the 50,000 strong crowd at Kennington, south London, began to melt away. In the meantime the government arrested most of them and turned half of London into an armed camp.

Chartism comprised a mixture of different groups

holding different ideas. Its leaders were divided between those who believed in

winning over the existing rulers, and those who believed in overthrowing them.

Though Chartism was not successful, its main demands, which were not conceded

in the 1832 Reform Act, were later incorporated in the Parliamentary Reform

Acts of 1867 and 1884.

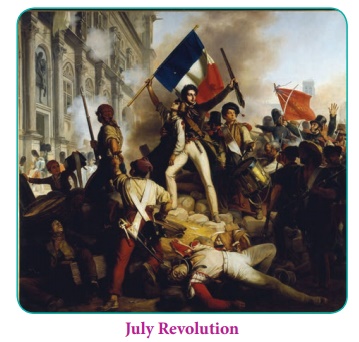

July Revolution (1830)

On 26 July 1830, the Bourbon king Charles X issued

four ordinances dissolving the Chamber of Deputies, suspending freedom of the

press, modifying the electoral laws so that three-fourths of the electorate

lost their votes, and calling for new elections to the Chamber. In protest, the

Parisian masses took to the streets for the first time since 1795. The royal

forces were unable to contain the insurrection. Charles X was advised to go

into exile and put in his place, a relative, Louis Philip of Orleans who had

the backing of the middle class. The tactics worked in France. But in other

parts of Europe there arose a number of risings. The revolution was successful

in the Netherlands, where Belgium was separated to form an independent state.

The Greeks, who had been fighting for independence from Turkish rule, attained

independence in 1832, with the support of the Great Powers. But the revolt of

Poles against the Russian Tsar was suppressed.

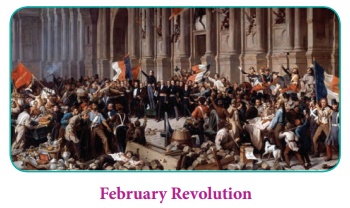

February Revolution (1848)

The French King, Louis Philippe, had to abdicate

and flee the country in February, 1848, when there was a spontaneous rising in

Paris. Crowds chanting “Vive de la reforme,” an expression in French to show

patriotism, stormed into the lines of troops and swarmed through the palaces

and the assembly buildings. The opposition rallied behind the French

revolutionary poet Lamartine. Louis Blanc also joined. In the elections held in

April 1848, on the basis of universal manhood suffrage, the moderates were

elected in large numbers. Only a few socialists were elected. The newly elected

Assembly decided to shut down the workshops that had been started at the

initiative of Louis Blanc, as the workshops were seen as a threat to social

order. The workers retaliated and braved the government repression. Between

June 24 and 26, thousands of people were killed and eleven thousand

revolutionaries were imprisoned or deported. The period came to be known as the

bloody June days. The Constituent

Assembly drafted a new constitution based on which elections were held. Louis

Napoleon, the nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte, was elected President in December

1848. Before long, in January 1852, he crowned himself as the Emperor by

holding a plebiscite. He assumed the title Napoleon III.

The year 1848 was one of the distinct triumphs for

nationalism. Metternich, the arbiter of Europe and enemy of nationality, was

forced to leave Vienna in disguise. Hungary and Bohemia both claimed national

independence. Milan expelled the Austrians. Venice became an independent

republic. Charles Albert, King of Sardinia, declared war against Austria.

Absolutism seemed dead for a while. But it was not to be. By the summer, the

monarchs had begun their attacks on the revolutionaries and succeeded in

crushing the democratic movements in important centres like Berlin, Vienna and

Milan. In the space of a year counter-revolution was victorious throughout the

continent.

Nationalism in southern and eastern Europe

In Europe the countries that first achieved

national unity were France, Spain and England. Italy which had made rich

contributions to art and letters was not part of this political change. Cities

in Italy like Rome, Florence, Venice, Naples and Milan were the capitals of

small states. Hence she became the prey of powerful kingdoms. Besides, the age

of Renaissance was an age of intellectual liberty and certainly not an age of

political liberty. The petty states of Italy, though enlightened in many ways,

were mostly governed by tyrants, such as the Medici in Florence, the cruel

Visconti in Milan and Caesar Borgia in central Italy. What was true of Italy

was true of Germany. The Holy Roman Empire was an empire only in name. In

practice, Germany contained three of four hundred separate States. It was their

kings who saved these countries from feudal anarchy and made them into nations.

Conditions suitable for the rise of Italy and Germany as nation states

developed only in the nineteenth century with the spread of nationalism.

Unification of Italy

Italy before Napoleon’s time was a patchwork of

little states and petty princes. Under Napoleon Italy had been reduced to three

political divisions. This step towards unity was destroyed by the Congress of

Vienna. Eight states were set up and the whole of Northern Italy was handed

over to the German-speaking Austrians. Italy in the nineteenth century was a

‘patchwork of about a dozen large states and a number of smaller ones.’

Metternich described Italy as “a mere geographical expression.” The empire of

Piedmont-Sardinia, in the northwest, bordering France, played a central role in

unifying Italy. To its east Lombardy and Venetia were under the control of the

Austrian Empire. It also controlled a few smaller states such as Tuscany, Parma

and Modena. The Papal States were located in the middle under the control of

the Roman Catholic Church. In the south was the Kingdom of the two Sicilies or

Naples and Sicily was under the control of a family of Bourbon dynasty.

The Napoleonic rule, for the first time, provided

Italy with a sense of unity through uniform administration. The nationalistic

aspirations of the Italians were dashed when the Congress of Vienna restored

the old monarchies in the various Italian principalities. The 1820s witnessed

the mushrooming of several secret societies such as the Carbonari, advocating liberal and patriotic ideas. They kept alive

the ideas of liberalism and nationalism. Revolts broke out in Naples, Piedmont

and Lombardy. However, they were crushed by Austria.

In the wake of the 1830 Revolution in France,

similar rebellions broke out in Modena, Parma and Papal States which were again

crushed by Austria. In 1848, following the February Revolution in France, the

people again rose in revolt in several Italian states including

Piedmont-Sardinia, Sicily, Papal States, Milan and Lombardy and Venetia. As a

result liberal constitutions were granted in Sicily, Piedmont Sardinia and the

Papal States. King Charles Albert of Piedmont-Sardinia, under the influence of

the Revolution, invaded Lombardy and Venetia. However, the Austrians defeated

him with the help of Russian troops. Charles Albert saved Piedmont-Sardinia

from Austrian occupation by taking the blame upon himself for the war and

abdicated in favour of his son Victor Emmanuel II. However, despite the defeat

of Pidemont-Sardinia and the suppression of revolution in various Italian

principalities, liberal and nationalistic ideas survived.

Mazzini, Count Camillo di Cavour, and Giuseppe Garibaldi

were the three central figures of the unification of Italy. Cavour was

considered the brain, Mazzini the soul and Garibaldi the sword-arm of Italian

Unification.

Mazzini (1805–1872)

Giuseppe Mazzini laid the foundations of the

Italian unification. Born in Genoa in a well-to-do family, he graduated in law.

Attracted to politics at a young age, he advocated the freedom of the Italian

nation. He involved himself in the insurrectionary activities of the Carbonari

for which he was arrested. He soon gave up the idea of secret plotting and

began to believe in open propaganda against monarchy. He believed that Italy

was a great civilisation that could provide leadership to the rest of the

world. He started the Young Italy movement in 1831 with the aim of an Italian

Republic. Exiled for working for the cause of unification of Italy in 1848,

when revolts were breaking out all over North Italy, Mazzini returned to Rome.

The Pope was driven away and a republic declared under a committee of three, of

which Mazzini was a member. But with the failure of 1848 Revolution and the

restoration of Rome to Pope with the support of the French, Mazzini carried on

his work by propaganda and preparing for the next programme of action.

Count Cavour (1810–1861)

Count Cavour was one of those inspired by the idea

of Italian nationalism. In 1847 he started a newspaper. The Italian unification

movement came to be known after the name of the newspaper as Il Risorgimento.

The Risorgimento (the resurrection of Italian spirit) was an ideological and literary movement that helped to arouse the national consciousness of the Italian people. Cavour rose to become the Prime Minister of Sardinia and played a crucial role in the unification of Italy. He used a combination of diplomacy and war to achieve the unification under the leadership of Sardinia. Cavour realised that Italian unification could not be achieved without international support. He needed the support of other Great powers to expel Austria from Lombardy and Venetia. Therefore, he involved Piedmont-Sardinia in the Crimean War to draw international attention and get the support of England and France. In July 1858, he struck an agreement with Napoleon III of France who offered to support Piedmont-Sardinia in its conflict with Austria.

War with Austria, 1859

Cavour then provoked war with Austria by mobilising

troops near the Austrian border. When Austria issued an ultimatum to disband

the troops he allowed it to expire. As a result Austria attacked

Piedmont-Sardinia in April 1859. The combined armies of Piedmont-Sardinia and

France defeated the Austrian armies. They won a major victory at the Battle of

Solferino. Instead of continuing the war, Napoleon III of France concluded a

peace agreement with the Austrian Emperor Francis Joseph II at Villa Franca on

11 July 1859. Cavour was disappointed at French withdrawal and resigned. In

November 1859, Piedmont-Sardinia and Austria concluded the Treaty of Zurich.

Austria ceded Lombardy but retained control over Venetia.

Cavour was reappointed as Prime Minister in 1860.

Parma, Modena and Tuscany were merged with the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia

through plebiscites. Similarly, Savoy and Nice were annexed to France on the

basis of plebiscites.

Garibaldi and the Conquest of Southern Italy

Giuseppe Garibaldi (1807–1882) played a key role in

the unification of Italy by waging guerilla warfare. He joined Mazzini’s Young

Italy and was influenced by his ideas. Participating in Mazzini’s rebellion in

Piedmont, he then fled to South America as an exile. He took up the cause of

revolutionaries there and fought for the cause of Rio Grande and Garibaldi

Uruguay against Argentinian occupation. Therefore, he was called the ‘Hero of

Two Worlds’. In 1843, he started the Italian Legion. This force of volunteers

came to be known as the Red Shirts.

Garibaldi accepted the invitation of the people of

Sicily in their revolt against their monarch. He left the port of Genoa with

1000 volunteers to Sicily. Landing unnoticed on the coast of Sicily he and his

volunteers defeated the 20000 strong Neapolitan (Naples) troops without any

loss of life. He then crossed into Naples and defeated the royal troops with

the help of the locals. However, Cavour, suspicious of Garibaldi’s triumphant

march, sent the Piedmontese force to stop him from invading Rome. Garibaldi

submitted his conquest to King Victor Emmanuel II and retreated to lead the

rest of his life in his home at the island of Caprera.

Plebiscites held in Sicily, Naples and Papal States

led to their merger with Piedmont-Sardinia. At the end of the war, Austria

retained control over Venetia and Pope held Rome. The rest of Italy was unified

under Piedmont. In May 1861, King Victor Emmanuel II was proclaimed by the

Parliament as the ruler of Italy. During the Austro-Prussian War in 1866, Italy

had allied itself with Prussia and was rewarded with Venetia. In 1871, Italy took

advantage of the Franco-Prussian War to annex Rome as the French forces

withdrew. Thus, the Italian Unification was completed.

Unification of Germany

In spite of a common language and many other common

features the German people continued to be split up into a large number of

States. Intellectuals such as Johann von Herder (1744–1803) and Friedrich

Schlegel (1772–1829) promoted the idea of German nation by glorifying its past.

Herder believed that civilisation was a product of the culture of the common

people, the Volk (folk) and promoted

the idea of a unique German spirit,

the Volkgeist. J.G. Fichte (1762–

1814) delivered a series of Addresses to

the German Nation. He claimed the

German spirit was not just one among

the many spirits but was superior to the rest. This inspired and promoted the

idea of nationalism among the Germans.

Before Napoleon Germany consisted

of about 360 principalities. Napoleon unconsciously gave an impetus to the

spirit of nationalism by forming a Confederation of the Rhine. For the first

time, it gave a sense of unity to Germany. However, the Congress of Vienna,

which transformed it into the German Confederation consisting of 39 states,

placed it under the control of Austria.

At the time of Fichte’s addresses Austria was

occupying the territories of Prussia, the largest and the most powerful of the

Confederation of German States. It kindled in Prussia the spirit to achieve its

past glory. It rebuilt and strengthened its army. Recruitment was based on

merit and not on old aristocratic standing. The zeal for liberalism and

modernisation combined with nationalism in Prussia.

In 1834, Prussia was successful in establishing the

Zollverein (customs union). By the

1840s it included most of the Germanic states except those under the control of

Austria and provided economic unity to the Germanic states. In 1848, popular

pressure led to the introduction of an elected legislative assembly.

In the same year the Frankfurt Assembly was

convened. Most of the elected members were liberals who believed that a liberal

national-German state could be created. They were divided on the question of

what constituted the German nation. The delegates who demanded ‘Great Germany’

believed that the German nation should include as many Germans as possible

including Austria except Hungary and the crown should be offered to the

Austrian Emperor. Some delegates put forward the idea of ‘Little Germany’ which

argued that Austria should be excluded from the German nation and the crown be

offered to King of Prussia. Eventually Austria withdrew from the Assembly. A

constitution was framed by the Assembly and the Little Germans offered the

constitutional monarchy to King Frederick William of Prussia. However, the

latter declined it as he did not want to accept the revolutionary notion of the

Assembly offering the crown to him.

Otto von Bismarck, Chancellor Prussia, transformed

it into a powerful state with the objective of uniting the Germanic states

under its leadership. He adopted a ‘blood and iron’ policy to achieve the

unification. He realised that the unification of Germany was not possible

without an armed conflict with Austria and France. He sparked conflict with

Austria and France through diplomatic moves. Bismarck opened negotiations with

Russia and ensured Russian neutrality in the event of a conflict between

Prussia and Austria. Bismarck had to fight three wars to achieve the

unification of Germany.

Bismarck remarked: Not through

speeches and resolutions of

majorities will the mighty problems of the age be solved, but by blood and

iron.

Schleswig–Holstein Question

Schleswig and Holstein were Germanic States under

the control of Denmark. In 1863, the King of Denmark merged these two duchies

into his kingdom. Bismarck proposed to Austria a joint action against Denmark.

In 1864, the joint forces of Prussia and Austria defeated Denmark. By the

Treaty of Vienna, Denmark surrendered the duchies to Prussia and Austria.

Differences arose on the fate of the Schleswig and Holstein. While Austria

wanted them to be made part of the German Confederation, Bismarck wanted to

administer them separately. By the Convention of Gastein in 1865 it was agreed

that Holstein would be under the control of Austria and Schleswig under the

control of Prussia. Holstein had a large German population and was located

within Prussian territory making it difficult for Austria to administer it.

When Austria decided to refer the matter to the Diet of the German

Confederation, it violated the Convention of Gastein. Bismarck ordered the

Prussian troops to occupy Holstein.

Austro–Prussian War of 1866

By his diplomacy Bismarck had ensured the

neutrality of Russia and France. He also got the support of Piedmont-Sardinia

which wanted to drive Austria out of Venetia. Thus ensuring that Austria would

not receive support from any major power, he forced Austria to attack Prussia.

The Austro-Prussian war is also known as the Seven Weeks’ War. Prussia defeated

Austria at the Battle of Sadowa or Konnniggratz in Bohemia. While the Prussian

army wanted to march into Austria and capture Vienna, Bismarck opposed it. The

war was brought to an end by the Treaty of Prague. Austria withdrew from the

German confederation. The northern states were formed into a North German

Confederation under Prussia. Though defeated, Italy was rewarded with Venetia

for its support to Prussia. The North German Confederation consisted of 22

states north of river Maine. A new constitution came into effect on 1 July

1867. Bismarck followed a friendly policy towards the southern states in an

attempt to win them over.

Franco–Prussian War of 1870–71

Bismarck next turned his attention to create a rift

between Prussia and France to unite the southern German states. The opportunity

came over the issue of succession to the Spanish throne. After a revolution in

Spain which drove Queen Isabella out of the country, the throne was offered to

Prince Leopold, a relative of the King of Prussia. France was agitated over the

issue. A threat of war was averted when Prince Leopold declined the offer.

Bismarck was disappointed.

However, a new opportunity arose when Gramont, the

French Foreign Minister met the King of Prussia in Ems. He demanded that

Prussia promise that it would not claim the throne of Spain in the future. The

Prussian King sent a telegram about the discussion to Bismarck. He edited it in

such a manner that the French thought their ambassador had been insulted while

the Prussians thought that their king had been humiliated. The Ems telegram

triggered the Franco-Prussian War.

France declared war on Prussia. In the Battle of

Sedan (2 September 1870) France was defeated. French King Napoleon III

surrendered. Bismarck however continued his march to Paris and captured it. The

war was brought to an end by the Treaty of Frankfurt in 1871. Bismarck imposed

harsh terms on France. France ceded Alsace-Lorraine and agreed to pay a huge

war indemnity. At the Versailles Palace, King William I of Prussia was declared

the Emperor of Germany which combined both the North German Confederation and

the southern states. Thus, the Unification of Germany was achieved by a

combination of diplomacy and warfare.

The Founding of the Third Republic in France

After the Battle of Sedan Napoleon III was

overthrown by a group of republicans in Paris. A provisional government was set

up to rule the country until a new constitution could be drafted. Elections

were held in February 1871 for a National Constituent Assembly. A majority of

the members were monarchists. It is not that the French people preferred a

monarchy, but rather that they longed for peace. The monarchists were

hopelessly divided and hence for almost four years a definite decision as to

the form of government could not be taken. Finally, in January 1875, the

National Assembly decided on a republican form of government. This signaled the

establishment of the Third Republic in France.

Paris Commune, 1871

In its bid to exact huge financial payment and to

possess French Alsace and Lorraine to Prussia, the Prussian army besieged

Paris. Paris held out through five months of siege in conditions of incredible

hardship with people starving and without fuel to warm their homes in winter.

Workers, artisans and their families bore the full brunt of the suffering as

prices soared. The Parisians grew bitter when bigger numbers of monarchists

were returned to the National Assembly. Then came the betrayal of the republic

– the appointment of 71-year-old Thiers. Paris was once again armed. As the

regular army had been disbanded under the terms of agreement with Prussia, the

Parisian masses kept their arms. Along with National Guards, now overwhelmingly

a working class body, they surrounded the soldiers. One of the generals,

Lecomte, gave orders to shoot at the crowd three times. But the soldiers stood

still. The crowd fraternised with the soldiers and arrested Lecomte and his

officers. That day Thiers and his government fled the capital. One of the

world’s great cities was in the hands of armed workers.

The Commune set about implementing measures in

their interests – banning night work in bakeries and handing over to

associations of workers any workshops or factories shut down by their owners,

providing pensions for widows and free education for every child, and stopping

the collection of debts incurred during the siege. In the meantime, the

republican government was organising armed forces to suppress the commune. It

succeeded in persuading Bismarck to release French prisoners of war. It

gathered them in Versailles, together with new recruits from the countryside.

Both the Central Committee of the National Guard and the Commune were composed

of Blanquists and Proudhanists. Marx could not influence events in Paris. Soon

the defeat of Commune was achieved by Thiers. Thereafter there was an orgy of

violence. Anyone who had fought for the Commune was summarily shot. Troops

patrolled the streets picking up poorer people at will and condemning them

death. It is estimated that between 20,000 and 30,000 were killed. Of the

40,000 communards (members of the commune) arrested, 5000 of them were

sentenced to be deported and another 5,000 to imprisonment.

Karl Marx had this to say on the Commune: “It

represented the greatest challenge the new world of capital had yet faced and

the greatest inspiration to the new class created by capital in opposition to

it.”

The Long Depression (1873–1896)

The world witnessed an unprecedented economic boom

during 1865–1873. The unification led to a phenomenal boom in Germany between

1870 and 1873. During this period 857 new companies were established. It was

unparalleled in the history of Germany. The railway system almost doubled in

size between 1865 and 1875. Tens of thousands of Germans invested in stock for

the first time to demonstrate both their patriotism and their faith in the

future of the new German Empire.

After the end of Civil War, the United States too

underwent an economic transformation, marked by the proliferation of big

business houses, and the massive development of agriculture attended with the

rise of national labour unions. The period from the 1870s to 1900 in the USA

came to be called the Gilded Age. The rapid expansion of industrialisation led

to a real wage growth of 60% between 1860 and 1890. The average annual wage per

industrial worker (including men, women, and children) rose from $380 in 1880

to $564 in 1890. However, the Gilded Age was also an era of abject poverty and

inequality, as millions of immigrants – many from impoverished regions – poured

into the United States. The high concentration of wealth in a few hands was

becoming more visible.

Then came the Depression. It was signalled by the

collapse of the Vienna Stock Market in May 1873. The Depression was world-wide

and lasted till 1896, and is referred to as the Long Depression. It affected

Europe and the US very much. American railroads became bankrupt. German shares

fell by 60 percent. Agriculture was most affected, as there was a fall in

prices. Many countries responded by imposing protective tariffs to prevent

competition.

The Gilded age was also an era of intense mass

mobilisation of working classes. Socialist and labour movements emerged in many

countries as a mass phenomenon. When industrial capitalism was at its peak in

the US, nearly 100,000 workers went on strike each year. In 1892, for example,

1,298 strikes involving some 164,000 workers took place across the nation.

Trade Unions, aiming at protecting workers’ wages, hours of labour, and working

conditions, were on the rise.

Capitalists who could not reconcile to the rise of

trade unions launched a counter offensive. The socialists suffered

persecution.The strike at the Carnegie Steel Company’s Homestead Steel Works in

1892 culminated in a gun battle between unionised workers and men hired by the

company to break the strike. The state supported the company management and as

a result the steelworkers ultimately lost the strike. The Pullman Strike of

1894, a national railroad strike, involving the American Railway Union, was

smashed by armed police and Pinkerton private detectives were hired by the

employers to shoot down strikers.

In Germany, the Socialist Democratic Party (SDP)

emerged as a popular party. However, Bismarck introduced anti-socialist

legislations to check the growth of socialism. Despite this support for the

party grew. With the repeal of the anti-socialist laws after 1890, socialist

trade unions were able to function openly. SDP’s share of Reichstag seats

increased from 3 percent in 1887 to 20 percent in 1903.

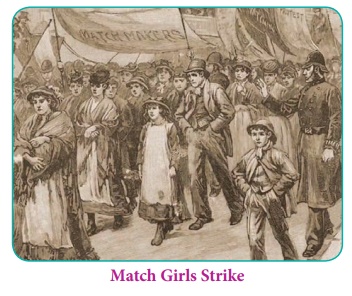

In Britain, in the 1880s, the famous Match Girls

Strike by the women and teenage girls working in Bryant and May Match Factory

ended in the victory of strikers. There was also a dock strike (1889) in the

port of London. Cardinal Manning intervened and mediated on behalf of the

strikers with the dock owners. But, in the 1890s, British employers, following

the examples of their counterparts in the US, also destroyed many of the new

unions through professional strike breakers, starving people back to work,

lockouts and the like.

Related Topics