Chapter: Aquaculture Principles and Practices: Integration of Aquaculture with Crop and Livestock Farming

Rice fish rotation

Rice–fish rotation

The constraints and conflicts mentioned above do not apply when fish

culture is practised in rotation with rice cultivation. The possible risk of

pesticide residue in fish has to be considered; however, the interval between

rice farming and fish stocking is long enough to allow degradation of

pesticides. Infestation by insect pests is also reduced, as their life cycles

are disrupted by the alternation of crops and associated practices. If

chemicals like carbofuran are used, the risk is further reduced. In countries

such as the Philippines where the yield of the wet-season rice crop is rather

low, it is logical to rear fish as an alternating crop.

When fish are to be raised in rotation, the fields are prepared after

the rice harvest. The bunds surrounding the field have to be raised and reinforced

where necessary, to maintain the required depth of water. The water level

depends on the habits of the species and their size. As the effect of water

level on the rice is not a constraint in this type of farming, an adequate

water level can be maintained if there is a suitable supply.

It is advantageous to flood the fields soon after harvesting the rice,

without removing the stubble. The submerged stubble provides the substrate for

the development of fish food organisms. When decomposed, they fertilize the

water and stimulate higher productivity. After the fish harvest, the residues

remaining in the soil serve as fertilizers for the rice crop.

The selection of species for culture depends to a large extent on the

likely duration of culture and the quality of the water. The practice of shrimp

production in rice fields on the west coast of India is carried out in areas

where generally only one crop (July to September) of a salt-resistant variety

of rice is grown. After the rice is harvested, the bunds are strength-ened and

suitable sluices installed to control the water supply. The brackish-water

lagoons nearby, from where water is obtained to irrigate the fields, have large

numbers of shrimp larvae at this time. The fields are filled with tidal water at

high tides and the larvae gain access to the fields with the water, where they

find shelter and food. Lamps may be hung above the inlets to attract the larval

shrimps. The natural process of stocking continues with every high tide for two

or three months. The sluice gates are provided with conical bag nets to prevent

escape of larvae and juvenile shrimps at low tides. Harvesting of shrimps

starts in December, by when the early stock will have reached marketable size.

Regular harvesting helps to thin the stock, leading to a better growth rate and

a higher percentage of larger shrimps. Several species of shrimps are grown in

the fields: Penaeus indicus, Macrobrachium rude and Palaemon styliferus. Incidental species

are Caridina gracilirostris, Acetes sp. and the finfishes, grey

mullets and pearlspot (Etroplus sp.).

The total yield per ha is reported to be around 780–2100kg. With increasing

interest in shrimp farming and the high price of shrimps, farmers now devote

greater attention to water management and stimulation of primary production in

the fields. Where possible, controlled stocking with sorted larvae is

undertaken. In the deltaic areas of eastern India flooded rice fields are

stocked with larvae of quick-growing shrimps, particularly Penaeus monodon and semisulcatus.

In rice fields irrigated with fresh water, either mono- or polyculture

of finfish is practised. The most common species are probably common carp,

tilapia and Trichogaster. The

snakehead (murrel) and the catfish, Clarias,

are also used. The use of goldfish (Carassius

auratus) and tench in Italy appears to have been discontinued. Similarly,

the production of buffalo fish (Ictiobus

cyprinellus) and channel catfish (Ictalurus

punctatus) as a rotational crop in rice field reservoirs in Arkansas appears

to be only on a very limited scale. Since the fields, when flooded after rice

harvest, serve as shallow ponds, some of the pond culture practices such as

fertilization and supplementary feeding can be adopted. Through proper water

management, a suitable water temperature and oxygen content have to be

maintained. Depending on the period available for fish farming, the stocking

rate and size can be determined. The duration of culture is generally three to

four months. Some farmers use the rice fields to grow fry to late fingerling

stage, or from late fingerling stage to marketable size. When tilapia are

cultured, special efforts are made to grow them to market size during this

period. Naturally the fish yield varies very considerably with species, culture

practices, etc. In well managed fields a yield of up to 700kg/ha can be

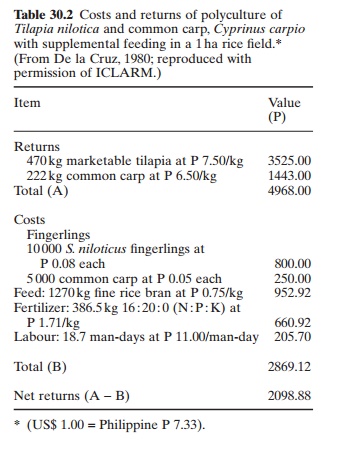

expected. De la Cruz (1980) gave the data (shown in Table 30.2) on costs and

returns for a rotational crop of tilapia and common carp in the Philippines,

for a culture period of about 116 days and a stocking rate of 10000 tilapia (Tilapia nilotica) and common carp.

Although the economics of the practice vary from place to place, these data

give some indication of the income that can be expected when fields left fallow

are used for fish culture. Available records show that the income from fish

farming is approximately the same as it would be if the fields were used for

rice production during the period it is left fallow. But under the circumstances

it adds to the income of the farmer and is a more efficient use of land and

farm resources.

In the traditional system of shrimp production, the production cost is

minimal when operated by the owner of the field. However, in a number of cases

the fields are leased from owners for shrimp growing and the cost of the lease

is relatively high. This influences the net return from shrimps. In improved

systems where sorted larvae and juveniles are stocked and fertilization or

feeding are adopted, the operational expenses are higher but the net income is

compensatingly high.

In rice fields in Louisiana (USA) the crayfish Procambarus clarkii is raised as a rotationalcrop. The culture techniques have been intensified in recent years. Adults are stocked at the rate of 6–12kg per ha in fields flooded after the rice is harvested, when the rice stubbles start to sprout. A depth of about 15– 45cm in maintained in the field and the crayfish feed on the rice stubble and various aquatic plants found in the field. After about six months they reach the marketable size of 10–15g. Larger ones weighing 40–45g fetch better prices and it takes about 8–14 months to reach that size. The usual yield is about 400–700kg per ha.

Related Topics