Chapter: Essential Clinical Immunology: Experimental Approaches to the Study of Autoimmune Rheumatic Diseases

Rheumatoid Arthritis: Etiology, Pathogenesis, Clinical Features, Treatment

RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS

Introduction and Epidemiology

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is the most common inflammatory arthritis. Its incidence worldwide is estimated to be between 0.5 and 1 percent of the general population.

Certain populations, such as the Pima Indians in North America, have a much higher incidence of RA (about 5 percent) than the general population. RA is one of many chronic inflammatory diseases that predominate in women. The ratio of female to male patients is estimated to be from 2:1 to 4:1.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

The etiology of RA has not been elucidated although a variety of studies suggest that a combination of environmental and genetic factors is responsible; a contribution of either one is necessary but not sufficient for full expression of the disease. A genetic component is demonstrated by studies of monozygotic twins, in whom the concor-dance rate is perhaps 30 to 50 percent when one twin is affected, compared with 1 per-cent for the general population. The immu-nogenetics is under intense study although there is a clear risk factor in the class II MHC haplotype of an individual. Addi-tional genes associated with RA include PTPN22 and STAT4.

The major pathology of RA is local-ized to the joints. The synovial membrane surrounding the joints becomes highly vascular and infiltrated with virtually all cellular components of the immune sys-tem. T and B lymphocytes are highly rep-resented and form lymphoid aggregates where B cells differentiate to antibody-forming cells. Poorly controlled produc-tion of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and inter-leukin-1 (IL-1), promote recruitment of additional inflammatory cells, and pro-duction of metalloproteinases contributes to tissue damage. The presence of immune complexes in joint fluid and direct deposi-tion of those complexes on the surface of cartilage support a direct role for autoan-tibodies in some aspects of RA inflamma-tion. Among the autoantibody specificities that have been implicated in RA patho-genesis are rheumatoid factor, an anti-body with specificity for the Fc portion of IgG, and anticyclic citrullinated pep-tide antibodies, which have been shown in some cases to precede development of clinical disease by years.

Clinical Features

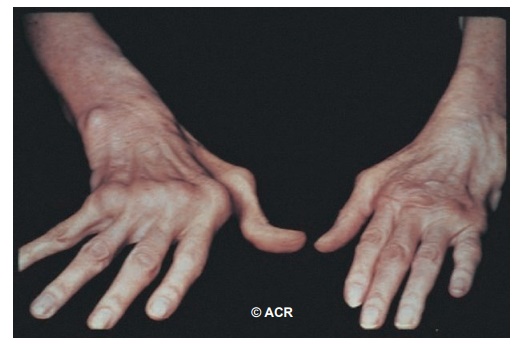

RA usually has a slow onset over the course of weeks to months. The initial symptoms may be systemic with indi-viduals presenting with fatigue, malaise, puffy hands, or diffuse musculoskeletal pain with joints becoming involved later. Articular involvement is usually symmet-ric although an asymmetric presentation with more symmetry developing later in the course of disease is not unusual (Figure 11.1). Morning stiffness that per-sists for at least one hour is characteristic of the disease and is related to the accu-mulation of edema fluid within inflamed tissues during sleep. The joints most com-monly involved first in RA are the small joints of the hands and feet, including the metacarpophalangeal joints, proximal interphalangeal joints, metatarsophalan-geal joints, and the wrists. Larger joints generally become symptomatic after small joints although patients can also present initially with large-joint involvement.

Although RA is primarily a disease of the joints, it is also clearly a systemic disease that can cause a variety of extra-articular manifestations involving major organ systems.

Figure 11.1 Metacarpalphalangeal joint swelling and ulnar deviation in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis.

Treatment of RA

Patients with RA have variable courses, ranging from those who progress rapidly to complete destruction of joints if left untreated, to those who, with few phar-macologic interventions, smolder along with minimal disease that leaves cartilage functional and activities of daily living unchanged from the premorbid state. The challenge for physicians is to determine into which category a patient falls. Treat-ment choices include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), which are useful to help control some of the inflam-matory signs of RA but do not prevent progression of the disease. A large class of drugs known as DMARDs (disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs) includes hydroxycholoroquine, an agent that has been shown to have anti-inflammatory properties in the disease but does not prevent erosive arthritis. Other DMARDs include those that have been shown to prevent joint destruction, which include sulfasalazine, methotrexate, leflunomide, and azathioprine. In recent years, the development of biologics targeting spe-cific cytokines, immune cells, and immune receptors have provided additional potent therapeutics with which to treat RA. In this category are three different drugs that target the TNF cytokine (etancercept, adalimumb, and infliximab), an IL-1 recep-tor antagonist (anakinra), an anti-CD20 antibody that selectively depletes B cells (rituximab), and a selective co-stimulation modulator that inhibits T-cell activation by binding to CD80 and CD86, thereby blocking CD28 interaction (abatacept).

Related Topics