Chapter: Information Architecture on the World Wide Web : Research

Research

Chapter 7

Research

So far, we've concentrated on the component

parts and principles of information architecture design. Now, we're going to

shift gears and explore the process that brings these components and principles

together to form useful, elegant information architectures.

If it were just a matter of applying a few

design principles to a web site, our jobs would be easy. However, as we

discussed earlier, information architecture doesn't happen in a vacuum. The

design of large sites requires an interdisciplinary team approach that involves

graphic designers, programmers, information architects, and other experts. For

everyone to collaborate effectively, you need to define and agree upon a relatively

structured development process. Even for smaller projects when teams might be

small and individuals might fill multiple roles, tackling the right challenges

at the right time is critical to success.

The next few chapters provide an overview of the

three major phases of site development. This chapter begins with a review of

existing background materials and quickly moves into a series of meetings aimed

at gathering and synthesizing information. In Chapter

8, we cover the creative brainstorming phase where you define the web

site. Chapter 9, shows how your ideas are put

to the test as the site is built, tested, and launched.

Throughout these chapters, we'll sometimes

refer to interactions with the client.

This language betrays our consulting backgrounds but also raises an important

point. As an architect, it's often useful to think like an outsider (even if

you're really an insider) so you can escape preconceived notions and think

outside the box.

Research is the first crucial step in the

construction or renovation of any large web site. You won't get too far if you

don't know what you're trying to do, and why.

Getting Started

If you want to create a successful web site,

you first must understand the big picture. For that reason, the first step in

the research process is to ask questions. You need to get everything out into

the open: the individual visions for the site, the raw materials at your

disposal, and any possible restrictions. Only then can you develop a solid

architecture for your web site.

Questions you need to ask include:

•

What are

the short- and long-term goals?

•

What can

you afford?

•

Who are

the intended audiences?

•

Why will

people come to your site?

•

What

types of tasks should users be able to perform?

•

What

types of content should and should not be part of the site?

You'll find that everyone has different

answers to these questions. Inevitably, we all bring personal, professional,

and departmental biases to the table. The architect is no exception: both the

architect and designer have their own biases and ambitions. To avoid wasted

work and complications later on, you need to get these out in the open as soon

as possible.

When you're architecting web sites, it's very

important to get the project off to a good start. You want everyone to feel

involved, enthusiastic, and confident that you know what you're doing. Let's

explore ways to make this happen.

1. Face-to-Face Meetings

Because of the political objectives and the

need to establish trust and respect, face-to-face meetings are essential during

the research phase. Only in meetings will you learn about the real goals of the

project and about the people you're working with. Only during face-to-face

conversations will you reach a comfort level that allows both you and your colleagues

to ask the difficult but necessary questions.

For example, a client once asked us to design

a web site that supported the needs of the parent company and its primary

subsidiary. Based upon telephone conversations with the client we believed that

the (misguided) plan for a single point of entry to information about both

organizations was already set in stone. We assumed the client had good reasons

for this integrated approach. However, at an early face-to-face meeting, it

became apparent that the client had not put a great deal of thought into this

decision. Fortunately, we became comfortable enough with the client at that

meeting to ask the obvious question. Within minutes, everyone agreed that two

sites were needed rather than one. This decision at such an early stage of the

project saved a great deal of potentially wasted time and money. It is often

difficult to ask such questions over the phone, because it's difficult to

establish a good comfort level without physical proximity and eye contact.

The meeting agenda is an important tool for

ensuring these sessions' productivity. By thinking through the key issues that

you'd like to cover, you'll be much better prepared for the ensuing

discussions. It's a good idea to involve clients and colleagues in the agenda

setting process, so that everyone's needs are being addressed. Agendas will

vary, depending on the project and the people involved; the sidebar on the

following page will give you a sense of what you might expect to cover during

an early meeting.

Information Architecture Meeting Agenda

1. Introductions

2. Web Site Critiques

What do you love and hate about the following sites?

3. Information Architecture Overview

What is information architecture?

Review of the process and deliverables.

Discussion of how both will fit into broader context of the project.

4. Project Scope

Are we architecting just the umbrella site or the sub-sites as well?

What are the respective priorities, timelines, and budget

considerations?

5. Centralization vs. Decentralization

Putting aside the web site for a second, to what extent do the

separate affiliates, departments, and subsidiaries share organizational

resources?

What is the strategy, goal, position, and target market for the

holding company?

Will the parent company's brand be stronger/weaker than the subsidiary

brands? Who will be responsible for collecting and maintaining content of the

umbrella site? Is it correct to assume that the content that we will be

classifying in the site is products and services, not individual subsidiaries?

In the site, will there be a need to provide unified packaging (e.g., guides,

indices) of products/services from separate subsidiaries?

6. Metrics for Success

Discuss possible goals for the site and opportunities to measure

success.

Potential to track leads, click throughs, media contacts, etc.

7. Umbrella Information Architecture

What are the major questions that audience members will have upon

arriving at the umbrella site?

What are the key ways they will want to navigate?

8. Discussion of Next Steps

2. Web Site Critiques

One of the best ways to break the ice with

clients and colleagues and move towards that important comfort level (while

conducting research at the same time) involves the review and discussion of

real-world web sites. It is much easier to express gut-level likes and dislikes

about particular sites than to talk abstractly about aesthetic and functional

preferences. It's also a lot more fun.

Show them web sites with a variety of

architectures. Some might be competitors' sites. Others might come from a

completely different industry. Invite them to suggest their own favorite sites

for review. As we discussed in the Section 1.1

exercise in Chapter 1, ask them what they love

and hate and why. Point out features or approaches that you find particularly

useful or useless. Don't be afraid to encourage or express strong feelings

about specific sites. As we suggested in Chapter 1,

passionate consumers become caring producers. A critique's transcript might

look something like this:

Participant A:

I hate this site because it's so difficult to

find the information I need. It's like looking for a needle in a haystack.

Participant B:

Yeah, and I can't stand their use of frames.

The pages are so chopped up and take forever to load.

Architect:

I agree. The graphic design and page layout

are poorly done. What do you think about the organization scheme?

Participant B:

There isn't one. There must be thirty links on

the main page. Some point to major content areas and some go to a single page.

It's horrible.

Architect:

Yes, you're right. It looks like they could

have used an audience-oriented architecture very successfully. Let's take a

look at a site that shows what I mean.

Not only are critiques a great way to

stimulate interesting and enthusiastic conversation while learning about

people's preferences, they're also a sneaky way to educate them. Use the

critique as an opportunity to explain and illustrate your ideas about what

makes a web site good. Notice that we used this devious yet effective technique

in the beginning of this book.

Be forewarned that participants may suggest

the critique of existing web sites or intranets created within their

organization. This is dangerous territory because some people in the room may

have been directly responsible for the design of these sites or may be good

friends with the site's designers. Proceed with caution to avoid hurting

feelings and creating enemies. Stress the fact that it's easy to criticize in

hindsight, try to encourage constructive criticism, and be sure to point out

some positive aspects of the site. In general, the tone of these meetings

should be kept light and cooperative.

The most obvious and common way to conduct web

site critiques is via a connection to the Internet. Ideally, the presentation

is conducted through a powerful computer with a reliable high-speed connection.

The computer needs a sufficiently recent version of Web browsing software with

all the necessary plug-in applications. Internet traffic congestion must not be

too heavy. The web sites you visit must be up and running. And of course, when

presenting on-site, the firewall must be negotiated.

As you quickly begin to see, many things can go wrong. Attempting to

explore the Web live during a meeting often brings technology to the foreground

in an intrusive way. There are better ways to solve this communication

challenge.

You can use offline browsers such as Web

Whacker15 that quickly and easily download and package selected web

sites on a floppy disk or hard drive, maintaining the integrity of links

between offline and online pages. This allows for navigation of web sites

without the problems associated with connectivity. However, keep in mind that

these offline browsers may not handle enabling technologies such as Java and

ActiveX. Also, note that even when using the safe approach of an offline

browser, you should have a print-based backup plan.

Murphy's Law (anything that can go wrong,

will) is particularly applicable to technology-based presentations. You might

even bring candles and matches in case of a power outage.

Alternatively, color prints of web sites

mounted on cards can be an attractive, portable way of presenting sites for

review. Multiple areas and levels of each site can be selected to show the ways

in which people can navigate and explore. It may seem silly to present web

sites on paper, but it works. By sending technology to the background where it

belongs, you can focus on communicating your ideas.

Whatever technology you choose to use, it's often

a good idea to assign site reviews as homework to be done before the meeting.

This will give people the time to think more deeply about what they do and

don't like. If you take this approach, you'll be rewarded with a more detailed

discussion, though perhaps at the expense of some spontaneity. Try it both ways

and see what you prefer.

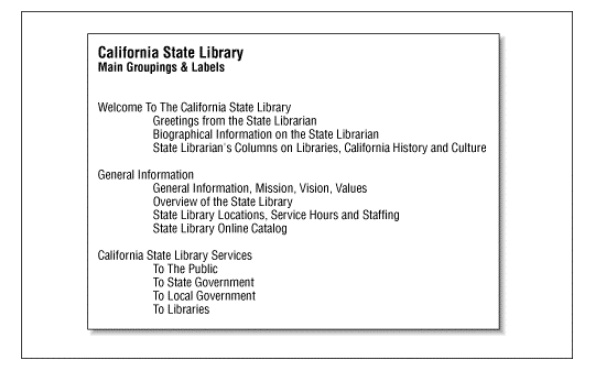

3. Information Architecture Critiques

Another way to get even more specific feedback

about architectural likes and dislikes is to have people critique the

information architectures of a few existing sites. To make them focus solely on

the architecture, provide them with a text-only view of the hierarchy of each

site, as shown in Figure 7.1.

Figure 7.1. Text-only view of a web site's hierarchy

You'll want to accompany the sample

architectures with specific exercises that tell people what you'd like them to

focus on. The sample exercise in the sidebar on the next page shows the types

of questions you might ask.

Sample Exercise: Information Architecture Critiques

The following pages contain representations of

the organization systems of three web sites. Please review each organization

scheme and answer the following questions:

1. A site's organization scheme involves the

placement of content into categories. Which organization scheme do you like

best? Why?

2. The labels used for the groupings of content

make a difference in a user's understanding of the site and their ability to

navigate its content. Which labels stand out in your mind as particularly good

ones? What makes them good? Which labels stand out in your mind as weaker ones?

Why?

3. Overall, which architecture do you like best

of these three? Why?

Related Topics