Chapter: Information Architecture on the World Wide Web : Research

Identifying Content and Function Requirements

Identifying Content and Function Requirements

One of the biggest challenges in information architecture

design is that of trying to get your arms around the intended content and

functionality of the web site. For a large site, this can be absolutely

daunting. The first step to success is realizing that you can't do it all at

once. The identification of content and function requirements may involve

several iterations. So just roll up your sleeves and get started.

1. Identifying Content in Existing Web Sites

As the Web matures, more and more projects

involve rearchitecting existing web sites rather than creating new ones from

scratch. In such cases, you're granted the opportunity to stand on the

shoulders of those who came before you. You can examine the contents of the

existing web site and use that content inventory as a place to begin.

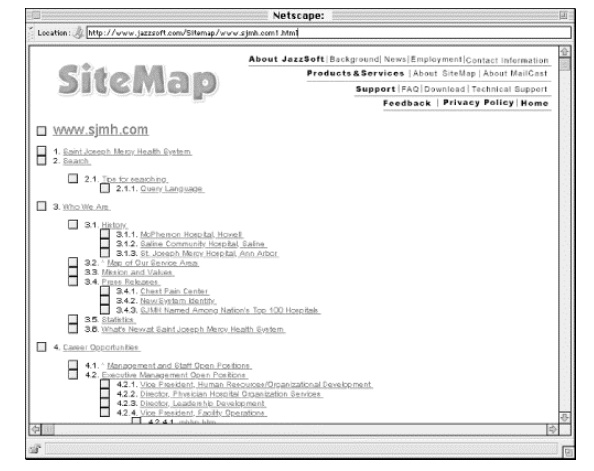

Rather than pointing and clicking your way

through hundreds or thousands of web pages, you should consider using an

automated site mapping tool such as SiteMap (see Figure

7.2).16 These tools generate a text-only view of the

hierarchy of the web site. If the original architects structured the hierarchy

and labeled page titles reasonably well, you should get a bird's-eye view of

the existing architecture and a nicely organized inventory of the site's

content. At this point, you're way ahead of the game. However, it's almost

certain that the site redesign will involve the addition of new content and the

integration of new applications, so don't think you get to escape from the

challenge of identifying content and function requirements.

Figure 7.2. SiteMap provides a quick and easy way to generate a

bird's-eye view of an existing web site's hierarchy. We typically print the

complete map for detailed review, especially if we're dealing with a large site

that has hundreds or thousands of pages.

2. Wish Lists and Content Inventory Forms

Many clients come to us with completely

unrealistic timelines in mind. It is not unusual for a client to approach us in

November stating that they want a world-class web site by the end of the year.

In the early days, this would send us into a world-class panic. "How can

we possibly build this site in 6 weeks?" we'd ask ourselves. "We'll

have to work 36 hours a day each." However, we soon learned this panic to

be unnecessary. Why? Because the greatest time-sink in Web and intranet design

projects involves the identification and collection of content, meaning that

the client, not us, quickly becomes the bottleneck.

Collecting content from people in multiple

departments takes time and effort. This is particularly true of large,

geographically distributed organizations. Some people and departments may care

about the project and respond quickly to requests for content. Others may not.

Content will reside in a multitude of formats ranging from Microsoft Word to

VAX/VMS databases to paper. Content may be limited for viewing by internal

authorized audiences or subject to copyright restrictions. Since it is

impossible to design an effective information architecture without a good feel

for the desired content, you can rest easy knowing that the client's

organization will soon become the bottleneck in the research phase.

However, that is not to say that the architect

is not responsible for guiding this content collection process. On the

contrary, your job is to help develop a process that efficiently and

effectively collects all content and information about content that you will

need to design and build the site. Wish lists and content inventory forms are

invaluable tools for such a process.

Your most immediate goal is to gather enough

information about the desired content to begin discussing possible

architectural approaches. In the early stages, you do not need or even want the

content itself. What you want is an understanding of the breadth and depth of

content that might be integrated into the site over time. You want the top of

the mountain, long-term view. Remember that you are trying to design for

growth. You don't want your vision to be limited by short-term format or

availability or copyright issues.

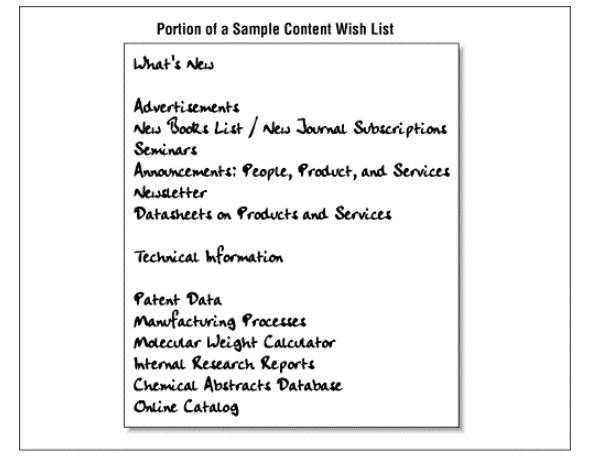

Wish lists are an excellent tool for this

information gathering task (see Figure 7.3).

Invite all relevant parties to create wish lists that describe the types of

content they would like to see on the web site. Make sure you include people

who deal with others' information needs on a regular basis (e.g., technical

support staff, librarians). Ask them to take a first stab at organizing that

content into categories. Involve senior managers and sales representatives,

information systems specialists and secretaries. If appropriate and practical,

involve representatives from the intended audiences as well. With these

relatively unstructured wish lists you can expect a fast turnaround time.

Within a week or so you can solicit, gather, and organize responses and begin

moving ahead with conceptual design. You will find that this process helps you

to define and prioritize the content for the web site.

Figure 7.3. As you can see, wish lists not only define the scope

of content, but also provide you with a good start at organizing the content

into categories.

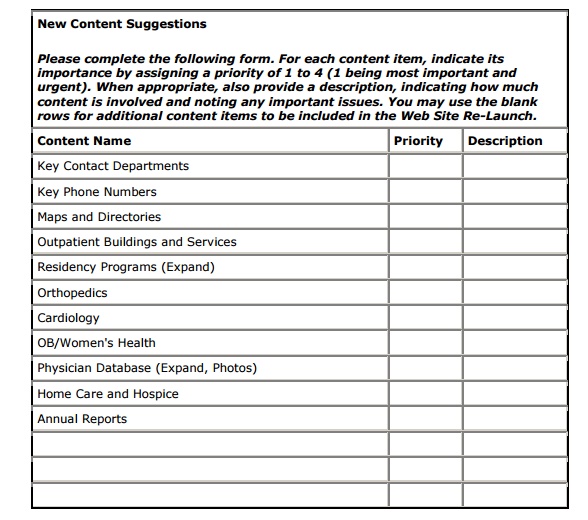

Once people have taken a first pass at the

wish list, you can compile the complete set of content requirements and ask the

same group to rank that content according to importance and urgency, as in the

example below. This type of structured form allows you to quickly learn about

the desired content and associated priorities.

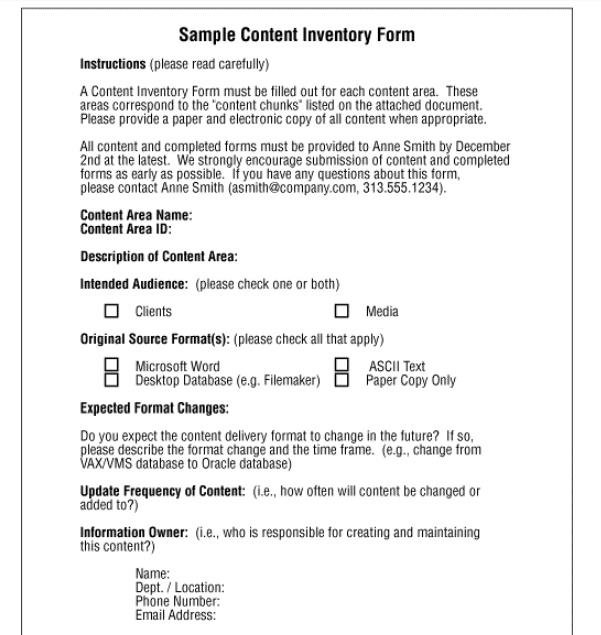

At this time, it is also important to begin a

parallel process of content collection, not because you need the content yet,

but because the process of collection takes a long time and can happen

independently of your architecture efforts. The efficient collection of content

in a large, distributed organization requires a highly structured process. A

content inventory form is a useful tool for bringing structure to this process.

The sample content inventory form in Figure 7.4 provides an idea of the types of questions

you might need to ask. You'll want descriptive information that includes a name

and unique identification number (used to connect the content inventory form

with print and electronic versions of the actual content). A brief content

description and an indication of the intended audience will often prove more

useful at this stage than seeing the content itself (which might really slow

things down).

Figure 7.4. Sample content inventory form

This form should be accompanied by

instructions that explain how to submit the response and by both print and

electronic versions of the content. Ideally, you will design a simple data

entry form that allows online submission of responses. You might use the Web as

the medium for distributing the form. We've also used common database

applications such as Microsoft Access.

In this way you can use a database as the repository

of all completed content inventory forms. This facilitates tracking progress

and content analysis. For example, you will be able to generate a report that

shows how much content is intended for a particular audience.

Related Topics