by Robert Wilson Lynd - Prose: Forgetting | 11th English : UNIT 3 : Prose: Forgetting

Chapter: 11th English : UNIT 3 : Prose: Forgetting

Prose: Forgetting

Forgetting

Now read the

humorous essay ‘Forgetting’ by Robert Lynd and his analysis of the fundamental

reasons for forgetfulness in humans.

A list of articles lost by railway travellers and now on sale at a great

London station has been published, and many people who read it have been

astonished at the absent-mindedness of their fellows. If statistical records

were available on the subject, however, I doubt whether it would be found that

absent mindedness is

common. It is the efficiency rather than the inefficiency of human memory that compels

my wonder. Modern man remembers even telephone numbers. He remembers the

addresses of his friends. He remembers the dates of good vintages.

He remembers

appointments for lunch and dinner. His memory is crowded with the names of

actors and actresses and cricketers and footballers and murderers. He can tell

you what the weather was like in a long-past August and the name of the

provincial hotel at which he had a vile meal during the summer. In his ordinary

life, again, he remembers almost everything that he is expected to remember.

How many men in all London forget a single item of their clothing when dressing

in the morning? Not one in a hundred. Perhaps not one in ten thousand. How many

of them forget to shut the front door when leaving the house? Scarcely more.

And so it goes on through the day, almost everybody remembering to do the right

things at the right moment till it is time to go to bed, and then the ordinary

man seldom forgets to turn off the lights before going upstairs.

There are, it must

be admitted, some matters in regard to which the memory works with less than

its usual perfection. It is only a very methodical man, I imagine, who can

always remember to take the medicine his doctor has prescribed for him. This is

the more surprising because medicine should be one of the easiest things to

remember. As a rule, it is supposed to be taken before during, or after meals

and the meal itself should be a reminder of it. The fact remains, however, that

few but the moral giants remember to take their medicine regularly. Certain

psychologists tell us that we forget things because we wish to forget them, and

it may be that it is because of their antipathy to pills and potions; that many people fail to remember them at

the appointed hours.

This does not

explain, however, how it is that a life-long devotee of medicines like myself

is as forgetful of them as those who take them most unwillingly. The very

prospect of a new and widely advertised cure-all delights me. Yet, even if I

have the stuff in my pockets, I forget about it as soon as the hour approaches

at which I ought to swallow it. Chemists make their fortunes out of the medicines people forget to take.

The commonest form

of forgetfulness, I suppose, occurs in the matter of posting letters. So common

is it that I am always reluctant

to trust a

departing visitor to post an important letter. So little

do I rely on his memory that I put him on his oath before handing the letter to

him. As for myself, anyone who asks me to post a letter is a poor judge of

character. Even if I carry the letter in my hand I am always past the first

pillar-box before I remember that I ought to have posted it. Weary of holding

it in my hand, I then put it for safety into one of my pockets and forget all

about it. After that, it has an unadventurous life till a long chain of

circumstances leads to a number of embarrassing questions being asked, and I am

compelled to produce the evidence of my guilt from my pocket. This, it might be

thought, must be due to a lack of interest in other people’s letters; but that

cannot be the explanation, for I forget to post some even of the few letters

that I myself remember to write.

As for leaving

articles in trains and in taxies, I am no great delinquent in such matters. I can remember almost anything except books

and walking-sticks and I can often remember even books. Walking-sticks I find

it quite impossible to keep.

I have an old-fashioned taste for them, and I buy them

frequently but no-sooner do I pay a visit to a friend’s house or go a journey

in a train, than another stick is on its way into the world of the lost. I dare

not carry an umbrella for fear of losing it. To go through life without ever

having lost an umbrella- has even the grimmest— jawed umbrella-carrier ever

achieved this?

Few of us, however,

have lost much property on our travels through forgetfulness. The ordinary man

arrives at his destination with all his bags and trunks safe. The list of

articles lost in trains during the year suggests that it is the young rather

than the adult who forget things, and that sportsmen have worse memories than

their ordinary serious-minded fellows. A considerable number of footballs and

cricket-bats, for instance, were forgotten. This is easy to understand, for

boys, returning from the games, have their imaginations still filled with a

vision of the playing-field, and their heads are among the stars — or their

hearts in their boots — as they recall their exploits or their errors. They are abstracted from the world outside them. Memories prevent them from

remembering to do such small prosaic

things as take the

ball or the bat with them when they leave the train.

For the rest of the

day, they are citizens of dreamland. The same may be said, no doubt, of anglers

who forget their fishing-rods. Anglers are generally said — I do not know with

what justification- to be the most imaginative of men, and the man who is

inventing magnificent lies on the journey home after a day’s fishing is bound

to be a little absent-minded in his behaviour. The fishing-rod of reality is

forgotten by him as he day-dreams over the fears of the fishing-rod of Utopia.

His loss of memory is really a tribute to the intensity of his enjoyment in

thinking about his day’s sport. He may forget his fishing-rod, as the poet may

forget to post a letter, because his mind is filled with matter more glorious.

Absent-mindedness

of this kind seems to me all but a virtue. The absent-minded man is often a man

who is making the best of life and therefore has no time to remember the mediocre. Who would have trusted Socrates or

Coleridge to post a letter? They had souls above such things.

The question

whether the possession of a good memory is altogether desirable has often been

discussed, and men with fallible

memories have

sometimes tried to make out a case for their

superiority. A man, they say, who is a perfect remembering machine is seldom a

man of the first intelligence, and they quote various cases of children or men

who had marvellous memories and who yet had no intellect to speak of. I

imagine, however, that on the whole the great writers and the great composers

of music have been men with exceptional powers of memory. The poets I have

known have had better memories than the stockbrokers I have known. Memory,

indeed, is half the substance of their art.

On the other hand,

statesmen seem to have extraordinarily bad memories. Let two statesmen attempt

to recall the same event — what happened, for example, at some Cabinet meeting

— and each of them will tell you that the other’s story is so inaccurate that

either he has a memory like a sieve or is an audacious perverter of the truth. The frequency with which the facts in

the autobiographies and speeches of statesmen are challenged, suggests that the

world has not yet begun to produce ideal statesmen—men who, like great poets,

have the genius of memory and of intellect combined.

At the same time,

ordinarily good memory is so common that we regard a man who does not possess

it as eccentric. I have heard of a father who,

having offered to take the baby out in a perambulator, was tempted by the sunny

morning to pause on his journey and slip into a public-house for a glass of

beer. Leaving the perambulator outside, he disappeared through the door of the

saloon bar. A little later, his wife had to do some shopping which took her

past the public-house, where to her horror, she discovered her sleeping baby. Indignant at her husband’s behaviour, she

decided to teach him a lesson.

She wheeled away

the perambulator, picturing to herself his terror when he would come out and

find the baby gone. She arrived home, anticipating with angry relish the white

face and quivering lips that would soon appear with the

news that the baby had been stolen. What was her vexation, however, when just before lunch her husband came in smiling

cheerfully and asking: “Well, my dear, what’s for lunch today?” having

forgotten all about the baby and the fact that he had taken it out with him.

How many men below the rank of a philosopher would be capable of such

absent-mindedness as this? Most of us, I fear, are born with prosaically

efficient memories. If it were not so, the institution of the family could not

survive in any great modern city.

About the Author

Robert Wilson Lynd (1879 – 1949), an Irish writer, is one of the greatest essayists of the 20th Century. He began his career as a journalist. He penned numerous articles for the leading newspapers and magazines like Daily News, The New Statesman and Nation. He wrote under the pseudonym ‘Y.Y.’ His essays cover a wide range of simple and interesting topics. They are humorous, delightful, ironical and satirical. Robert Lynd was awarded with an honorary literary Doctorate by Queen’s University, Belfast in 1947. He was also honoured by the Royal Society of Literature with a silver medal and by The Sunday Times with a gold medal for Belles Lettres. In his essay ‘Forgetting’, Robert Lynd takes a humourous look at the nature and effects of forgetfulness.

A. How sharp is your memory?

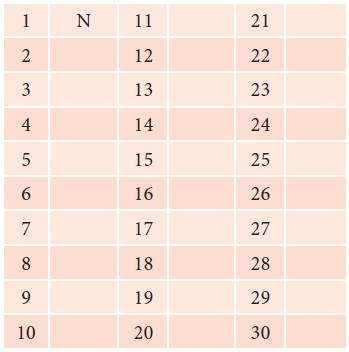

Take this five-minute memory test. The teacher will read out a series of 30 words, one by one. Some of them will be repeated. Whenever you hear a word for the first time, write ‘N’ (for New) in the corresponding box and when you hear a repeated word write ‘R’. After completing this task, check your results. Compare it with your friends and see where you stand.

B. Have you ever lost or misplaced anything of value due to forgetfulness?

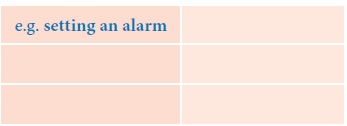

At times, instances of forgetfulness may land us in a tight spot or in a difficult situation. Therefore, we need to find ways to remember what we have to do or carry with us. One way is to make a mental check-list that we can verify before starting any activity.

Now discuss with your partner and think of some practical ideas to overcome forgetfulness, in your day-to-day activities.

C. Discuss and share your views with the class on the following.

Is forgetfulness a result of carelessness or preoccupation?

Related Topics