Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Psychopathology Across the Life-Cycle

Problems of Early Adulthood

Problems of Early Adulthood

The period between the ages of 20 and 30 years is

commonly referred to as early adulthood.

Early Adult Development

Developmental tasks of early adulthood include achieving emo-tional and financial independence from parents and forming intimate relationships with people outside the family of origin. Stage-specific stressors include leaving home, education and career choice, in some cases service in the armed forces, find-ing and maintaining employment, courtship and marriage, and sexual relations, among others.

Types of Problems

Problems of young adulthood fall mostly into the

categories listed in Table 8.8. By the end of early adulthood, people have

passed through the ages of greatest risk for first onset of the majority of

recognized mental disorders. Comorbidity between disorders becomes the rule

rather than the exception. In a population sur-vey in the USA, 14% of those

evaluated had three or more life-time disorders and accounted for more than 50%

of the mental disorders found, both on a lifetime basis and in the year before

the assessment (Kessler et al.,

1994).

The relationships between comorbid “disorders” are

complex. Whether they indeed represent independent entities with distinctive

etiologies, pathogenetic mechanisms and outcomes, or merely reflect different

ways in which fundamental psychopathological disturbances are manifest over

time, between sexes, or across aspects of psychological functioning remains to

be determined. In some cases, one disorder is clearly antecedent to another.

Examples include disorders of childhood, such as separation anxiety disorder or

conduct disorder, that evolve into adult versions – in these cases, panic

disorder with agoraphobia or antisocial personality disorder, respectively.

Sometimes, as in the case of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, residual

symptoms persist and form the basis for developing problems such as substance

abuse or personality dysfunction. At other times, a second disorder may develop

as a consequence of a primary disorder – in reaction to it or as a

complication. Examples include

major depressive disorder developing after a person

has been incapacitated by panic disorder with agoraphobia, or sedative,

anxiolytic, or alcohol abuse developing because the person attempted to

self-medicate for the condition. Alternatively, disorders appear more or less

contemporaneously and reflect an underlying diathesis or vulnerability. Thus,

patients present with several disorders, all suggestive of a problem of

generalized impulsivity, such as bulimia nervosa, a substance use disorder and

an impulse control disorder (e.g., kleptomania). Personality disorders often

develop in the context of underlying traits affecting specific capacities such

as impulse control or interpersonal relatedness, as dysfunction becomes

widespread.

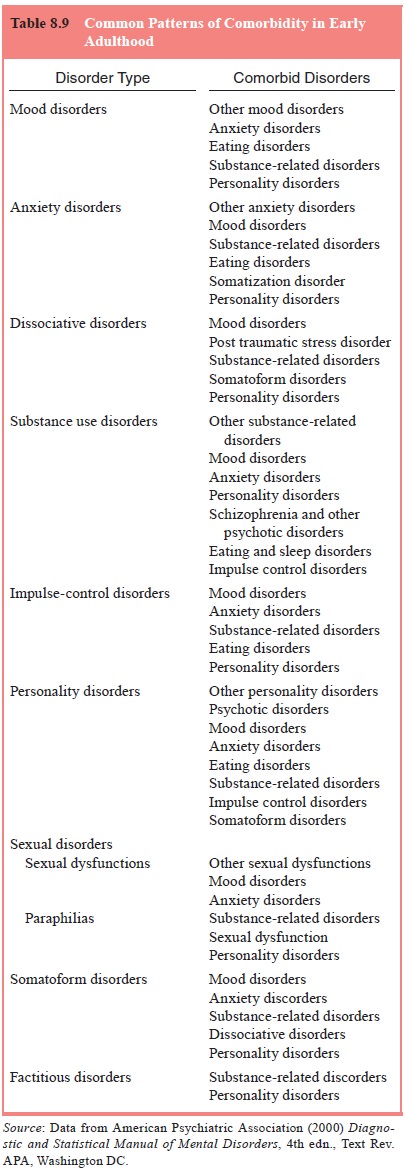

Table 8.9 summarizes patterns of comorbid mental

disor-ders in early adulthood.

Emotional Problems

Although disturbances in mood can occur at any age,

the peak ages of onset of mood disorders are probably in the twenties. Mood

disturbances may be acute and episodic or insidious and chronic. They may be

relatively mild or severe and may be ac-companied by psychotic features or

suicidal behavior. The most common mood disorders are major depressive

disorder, dys-thymic disorder, bipolar disorder and cyclothymic disorder.

Although several anxiety disorders have their onset

most often in childhood or adolescence, as previously described, others have

increased risk for onset in early adult life. In particular, many cases of

acrophobia (fear of heights) and situational phobias, such as of elevators,

flying, or closed places, develop in early adulthood (American Psychiatric

Association, 2000). There is a rise in the rate of panic disorder in women in

early and middle adult life (Regier et

al., 1988). Obsessive–compulsive disorder has a later age at onset in women

than in men, during the twenties rather than the teens. Acute stress disorder

and PTSD can occur at any age but are prevalent in young adults.

Disorders such as panic disorder, other specific

phobias, social phobia and generalized anxiety disorder, which are more likely

to begin in childhood or adolescence, may persist or recur during early adult

life.

The severity, duration and proximity of a person’s

expo-sure to a traumatic event influence the risk of developing either an acute

stress disorder or PTSD (March, 1993). Acute stress reactions which do not

resolve (Classen et al., 1998),

peritrau-matic dissociation (Shalev et

al., 1996) or emotional numbing in response to the stressor (Epstein et al., 1998) predict later PTSD. Social

support, family history, childhood experiences, personal-ity variables and

preexisting mental disorders also affect risk. Men and women appear equally

vulnerable. Dissociative dis-turbances may occur in the absence of

reexperiencing or avoid-ance symptoms, often in response to severe stress

(Spiegel and Cardena, 1991).

Milder, time-limited reactions to stressors of any

severity may also occur. These are common occurrences that might follow the

breakup of a romantic relationship or the loss of a job. The symptoms may be of

depression, anxiety, or disturbance of conduct. They cause temporarily

decreased performance at school or work or impairment in social relationships.

Provided that the consequences of the stressor are resolved (i.e., the person

resumes dating or obtains a new job), the course of the symptoms and impairment

should be less than 6 months.

Behavior and Adaptive Functioning

Problems with various types of impulsive behaviors and problems with adaptive functioning in general seem particularly prone to become manifest in early adulthood. These problems may de-velop, in part, secondary to the increased stresses of movement away from the protective environments of school and family that characterize the period.

Of major significance in the twenties is the

stabilization of patterns of perceiving, relating to, and thinking about the

envi-ronment and oneself that we call personality. Also, however, in the

twenties, the potential for the development of inflexible and maladaptive

traits that cause distress or interfere with effective social and occupational

functioning may arise. Thus, personality disorders may become evident.

Disturbances in Physical Functioning

Certain disturbances in physical functioning are

likely to become manifest in early adult life. These include disturbances in

sexual functioning, sleep disturbances and some physical complaints that cannot

be fully explained on the basis of a known general medical condition.

Certain disturbances characterized by physical

complaints without known medical etiology have a high incidence rate in early

adulthood. Specifically, conversion reactions, hypochon-driasis and

somatization disorder can be first diagnosed in this age group.

Problems in Reality Testing

Problems in reality testing are reflected in

abnormalities of speech, thinking, perception and self-experience. They are

sug-gestive of psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia. Although

schizophrenia and its counterpart disorder of briefer duration, schizophreniform

disorder, may have an onset in late adoles-cence (or in later adulthood), the

most common age at onset is in early adult life.

Patients who have illness episodes that are

character-ized by major episodes of mood disturbance, either depressed or

manic, accompanied by schizophrenia-like psychotic symp-toms and whose

delusions and hallucinations are also present when mood symptoms are not, are

said to have schizoaffective disorder.

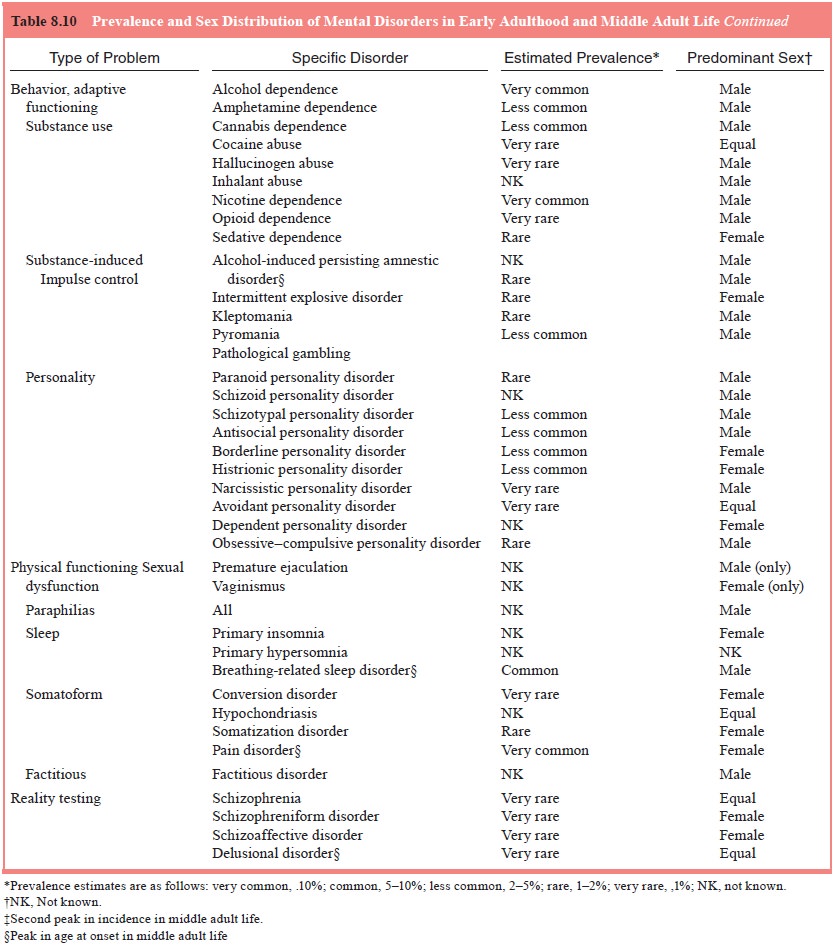

The vast majority of disorders with typical onset

in early adult life persist or recur in middle adult life. Some of these

disorders may also have their initial onset after age 30 years. Table 8.10

summarizes the estimated prevalence and sex distri-bution of mental disorders

of early adulthood.

Related Topics