Definition, Causes, Signs and Symptoms, Stages, Risk Factors, Prevention - Pressure Ulcer | 11th Nursing : Chapter 8 : Nursing Procedures

Chapter: 11th Nursing : Chapter 8 : Nursing Procedures

Pressure Ulcer

Pressure Ulcer

Definition

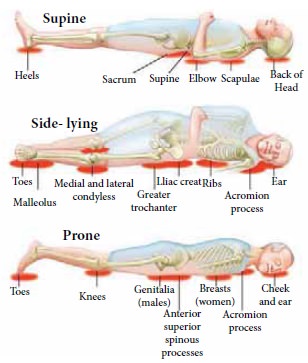

Pressure ulcers, also known as pressure sores, pressure injuries, bedsores, and decubitus ulcers, are localized damage to the skin and/or underlying tissue that usually occur over a bony prominence as a result of pressure, or pressure in combination with shear and/ or friction.

The most common sites

are the skin overlying the sacrum, coccyx, heels or the hips, but other sites

such as the elbows, knees, ankles, back of shoulders, or the back of the

cranium can be affected.

Causes

Pressure ulcers occur

due to pressure applied to soft tissue resulting incompletely or partially

obstructed blood flow to the soft tissue. Shear is also a cause, as it can pull

on blood vessels that feed the skin. Pressure ulcers most commonly develop in

individuals who are not moving about, such as those being bedridden or confined

to a wheelchair.

There are four

mechanisms that contribute to pressure ulcer development:

External (interface) pressure applied over an area of the body, especially

over the bony prominences can result in obstruction of the blood capillaries,

which deprives tissues of oxygen and nutrients, causing ischemia (deficiency of

blood in a particular area), hypoxia (inadequate amount of oxygen available to

the cells), edema, possible onset of osteomyelitis, inflammation, and, finally

necrosis and ulcer formation. Ulcers due to external pressure occur over the

sacrum and coccyx, followed by the trochanter and the calcaneus (heel).

Friction is damaging to the superficial blood vessels directly under the skin. It occurs when two surfaces

rub against each other. The skin over the elbows and can be injured due to

friction.

Shearing is a separation of the skin from underlying tissues. When a patient is partially sitting up in bed,

their skin may stick to the sheet, making them susceptible to shearing in case

underlying tissues move downward with the body toward the foot of the bed.

Moisture is also a common pressure ulcer culprit. Sweat, urine, feces, or excessive wound drainage can

further exacerbate the damage done by pressure, friction, and shear.

Signs and Symptoms

The early signs of

pressure ulcers are

·

Unusual changes in skin color or texture

·

Swelling Tenderness Discomfort

·

Pus-like draining

·

An area of skin that feels cooler or warmer to the touch than

other areas

·

Local oedema

·

Later the area becomes blue purple and mottled

·

Due to continued pressure, the circulation is cut-off, the

gangrene develops and the affected area is sloughed off..

Stages of Pressure Sores

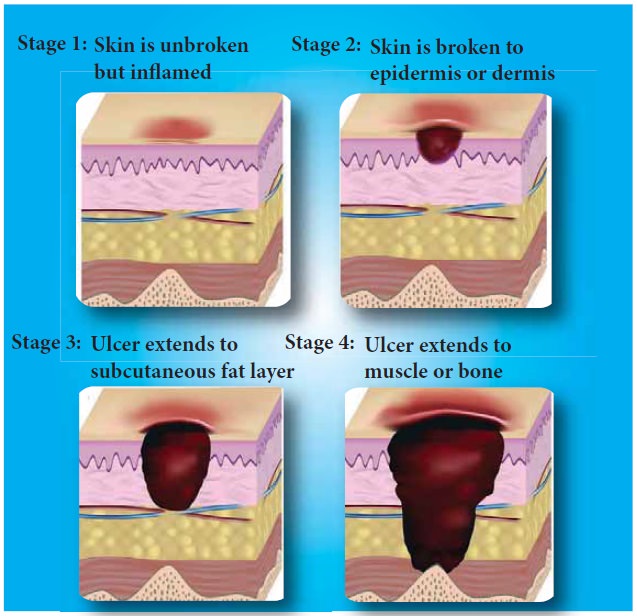

Stage 1

Intact skin with

non-blanch and redness of a localized area usually over a bony prominence.

Stage 2

Partial thickness,

loss of dermis presenting as a shallow open ulcer with a red pink wound bed

without slough may also present as an intact or open/ruptured serum filled

blister. Also presents as a shiny or dry shallow ulcer without slough or

bruising. This stage should not be used to describe skin tears, tape burns,

perinea dermatitis, maceration or excoriation

Stage 3

Full thickness, tissue

loss, subcutaneous fat may be visible but bone, tendon or muscle are not

exposed.

Stage 4

Full thickness tissue

loss with exposed bone, tendon or muscle. Slough or eschar may be present on

some parts of the wound bed.

Unstageable

Full thickness tissue

loss in which actual depth of the ulcer is completely obscured by slough

(yellow, tan, gray, green or brown) and/or eschar (tan, brown or black) in the

wound bed. Until enough slough and/or eschar is removed to expose the base of the

wound, the true depth, and therefore stage, cannot be determined.

Suspected Deep Tissue Injury

A purple or maroon

localized area of discoloured intact skin or blood-filled blister due to damage

of underlying soft tissue from pressure and/or shear. The area may be preceded

by tissue that is painful, firm, mushy, boggy, warmer or cooler as compared to

adjacent tissue.

Areas Prone to Develop Pressure Sore

Risk Factors

Factors that may place

a patient at risk include

·

immobility,

·

diabetes mellitus

·

peripheral vascular disease malnutrition

·

cerebro-vascular accident and hypotension.

·

Other factors are age of 70 years and older,

·

current smoking history, dry skin,

·

low body mass index,

·

urinary and fecal incontinence,

·

physical restraints,

·

malignancy, and history of pressure ulcers.

Prevention

Redistributing pressure:

The most important

care for a person at risk for pressure ulcers and those with bedsores is the

redistribution of pressure so that no pressure is applied to the pressure

ulcer.

Support surfaces

Many support surfaces

redistribute pressure by immersing and/or enveloping the body into the surface.

Some support surfaces, including anti decubitus mattresses and cushions,

contain multiple air chambers that are alternately pumped. Methods to

standardize the products and evaluate the efficacy of these products have only

been developed in recent years.

Nutrition

In addition, adequate

intake of protein and calories is important. vitamin C has been shown to reduce

the risk of pressure ulcers. People with higher intakes of vitamin C have a

lower frequency of bed sores in those who are bedridden than those with lower

intakes.

Treatment

The treatment includes

the use of bed rest, pressure re distributing support surfaces, nutritional

support, repositioning, wound care (e.g. debridement, wound dressings) and

biophysical agents (e.g. electrical stimulation). Reliable scientific evidence

to support the use of many of these interventions, though, is lacking.

The following steps should

be taken:

·

Remove the pressure from the sore by moving the patient or using foam

pads or pillows to prop up parts of the body.

·

Clean the wound: Minor wounds may be gently washed with water and a

mild soap. Open sores need to be cleaned with a saline solution each time the

dressing is changed.

·

Control incontinence as far as possible.

·

Remove dead tissue: A wound does not

heal well if

dead or infected tissue is present, so debridement is

necessary.

·

Apply dressings: These protect the wound and accelerate healing. Some

dressings help prevent infection by dissolving dead tissue.

·

Use oral antibiotic cream: These will help treat an infection.

Debridement

Necrotic tissue should

be removed in most pressure ulcers. The heel is an exception in many cases when

the limb has an inadequate blood supply. Necrotic tissue is an ideal area for

bacterial growth, which has the ability to greatly compromise wound healing.

There are five ways to remove necrotic tissue.

1.

Autolytic debridement is the use of moist dressings to promote autolysis

with the body’s own enzymes and white blood cells.

2.

Biological debridement, or maggot debridement therapy, is the use of

medical maggots to feed on necrotic tissue and therefore clean the wound of

excess bacteria. Although this fell out of favor for many years, in

January2004, the FDA approved maggots as a live medical device.

3.

Chemical debridement, or enzymatic debridement, is the use of prescribed

enzymes that promote the removal of necrotic tissue.

4.

Mechanical debridement, is the use of debriding dressings,

whirlpool or ultrasound for slough in a stable wound

5.

Surgical debridement, or sharp debridement, is the fastest

method, as it allows a surgeon to quickly remove dead tissue.

Dressing

Some guidelines for

dressing are

Condition Cover dressing

None to moderate

exudates - Gauze with tape or composite.

Moderate to heavy

exudates - Foam dressing with tape or composite

Frequent soiling -

Hydrocolloid dressing, film or composite

Fragile skin -Stretch

gauze or stretch net

Related Topics