Chapter: Basic & Clinical Pharmacology : Special Aspects of Geriatric Pharmacology

Pharmacologic Changes Associated With Aging

PHARMACOLOGIC CHANGES ASSOCIATED

WITH AGING

In

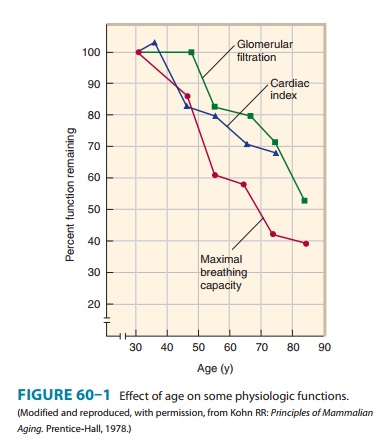

the general population, measurements of functional capacity of most of the

major organ systems show a decline beginning in young adulthood and continuing

throughout life. As shown in Figure 60–1, there is no “middle-age plateau” but

rather a linear decrease beginning no later than age 45. However, these data

reflect the mean and do not apply to every person above a certain age;

approximately one third of healthy subjects have no age-related decrease in,

for example, creatinine clearance up to the age of 75. Thus, the elderly do not

lose specific functions at an accelerated rate compared with young and

middle-aged adults but rather accumulate more deficiencies with the passage of

time. Some of these changes result in altered pharmacokinetics. For the

pharmacologist and the clinician, the most important of these is the decrease

in renal func-tion. Other changes and concurrent diseases may alter the

pharma-codynamic characteristics of particular drugs in certain patients.

Pharmacokinetic Changes

A. Absorption

There is little

evidence of any major alteration in drug absorption with age. However,

conditions associated with age may alter the rate at which some drugs are

absorbed. Such conditions include altered nutritional habits, greater

consumption of nonprescription drugs (eg, antacids and laxatives), and changes

in gastric emptying, which is often slower in older persons, especially in

older diabetics.

B. Distribution

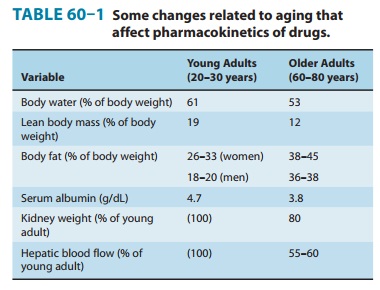

Compared with young

adults, the elderly have reduced lean body mass, reduced body water, and

increased fat as a percentage of body mass. Some of these changes are shown in

Table 60–1. There is usually a decrease in serum albumin, which binds many

drugs, especially weak acids. There may be a concurrent increase in serum orosomucoid (α-acid glycoprotein), a protein that binds many

basic drugs. Thus, the ratio of bound to free drug may be signifi-cantly

altered. As explained, these changes may alter the appropriate loading dose of

a drug. However since both the clearance and the effects of drugs are related

to the free concentra-tion, the steady-state effects of a maintenance dosage

regimen should not be altered by these factors alone. For example, the loading

dose of digoxin in an elderly patient with heart failure should be reduced (if

used at all) because of the decreased apparent volume of distribution. The

maintenance dose may have to be reduced because of reduced clearance of the

drug.

C. Metabolism

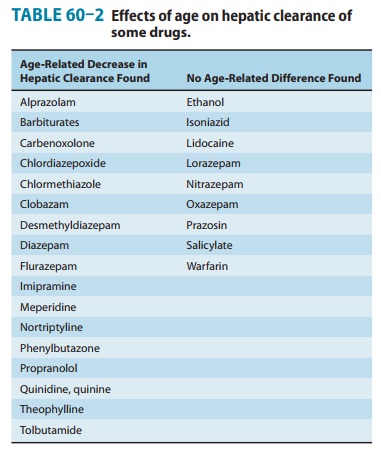

The capacity of the

liver to metabolize drugs does not appear to decline consistently with age for

all drugs. Animal studies and some

The great-est changes are in phase I reactions, ie, those carried out by microsomal P450 systems. There are much smaller changes in the ability of the liver to carry out conjugation (phase II) reactions . Some of these changes may be caused by decreased liver blood flow (Table 60–1), an important variable in the clearance of drugs that have a high hepatic extraction ratio. In addition, there is a decline with age of the liver’s ability to recover from injury, eg, that caused by alcohol or viral hepatitis.

Therefore, a history of recent liver disease in

an older person should lead to caution in dosing with drugs that are cleared

primarily by the liver, even after apparently complete recovery from the

hepatic insult. Finally, malnutrition and diseases that affect hepatic

function—eg, heart failure—are more common in the elderly. Heart failure may

dramatically alter the abil-ity of the liver to metabolize drugs by reducing

hepatic blood flow. Similarly, severe nutritional deficiencies, which occur more

often in old age, may impair hepatic function.

D. Elimination

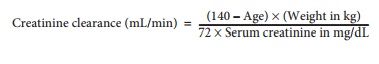

Because

the kidney is the major organ for clearance of drugs from the body, the

age-related decline of renal functional capacity is very important. The decline

in creatinine clearance occurs in about two thirds of the population. It is

important to note that this decline is not reflected in an equivalent rise in

serum creati-nine because the production of creatinine is also reduced as

muscle mass declines with age; therefore, serum creatinine alone is not an

adequate measure of renal function. The practical result of this change is

marked prolongation of the half-life of many drugs, and the possibility of

accumulation to toxic levels if dosage is not reduced in size or frequency.

Dosing recommendations for the elderly often include an allowance for reduced renal

clearance. If only the young adult dosage is known for a drug that requires

renal clearance, a rough correction can be made by using the Cockcroft-Gault formula, which is

applicable to patients fromages 40 through 80:

For

women, the result should be multiplied by 0.85 (because of reduced muscle

mass). It must be emphasized that this estimate is, at best, a population estimate and may not apply to

a particular patient. If the patient has normal renal function (up to one third

of elderly patients), a dose corrected on the basis of this estimate will be

too low—but a low dose is initially desirable if one is uncertain of the renal

function in any patient. If a precise measure is needed, a standard 12- or

24-hour creatinine clearance determi-nation should be obtained. As indicated

above, nutritional changes alter pharmacokinetic parameters. A patient who is

severely dehydrated (not uncommon in patients with stroke or other motor

impairment) may have an additional marked reduc-tion in renal drug clearance

that is completely reversible by rehydration.

The

lungs are important for the excretion of volatile drugs. As a result of reduced

respiratory capacity (Figure 60–1) and the increased incidence of active

pulmonary disease in the elderly, the use of inhalation anesthesia is less

common and parenteral agents more common in this age group.

Pharmacodynamic Changes

It

was long believed that geriatric patients were much more “sensitive” to the

action of many drugs, implying a change in the pharmacodynamic interaction of

the drugs with their receptors. It is now recognized that many—perhaps most—of

these appar-ent changes result from altered pharmacokinetics or diminished

homeostatic responses. Clinical studies have supported the idea that the

elderly are more sensitive to some

sedative-hypnotics and analgesics. In addition, some data from animal studies

suggest actual changes with age in the characteristics or numbers of a few

receptors. The most extensive studies suggest a decrease in responsiveness to β-adrenoceptor

agonists. Other examples are discussed below.

Certain

homeostatic control mechanisms appear to be blunted in the elderly. Since

homeostatic responses are often important components of the overall response to

a drug, these physiologic alterations may change the pattern or intensity of

drug response. In the cardiovascular system, the cardiac output increment

required by mild or moderate exercise is successfully provided until at least

age 75 (in individuals without obvious cardiac dis-ease), but the increase is

the result primarily of increased stroke volume in the elderly and not

tachycardia, as in young adults. Average blood pressure goes up with age (in

most Western coun-tries), but the incidence of symptomatic orthostatic

hypotension also increases markedly. It is thus particularly important to check

for orthostatic hypotension on every visit. Similarly, the average 2-hour

postprandial blood glucose level increases by about 1 mg/dL for each year of

age above 50. Temperature regulation is also impaired, and hypothermia is

poorly tolerated by the elderly.

Behavioral & Lifestyle Changes

Major changes in the

conditions of daily life accompany the aging process and have an impact on

health. Some of these (eg, forget-ting to take one’s pills) are the result of

cognitive changes associ-ated with vascular or other pathology. Others relate

to economic stresses associated with greatly reduced income and, possibly,

increased expenses due to illness. One of the most important changes is the

loss of a spouse.

Related Topics