Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Management of Patients With Immunodeficiency

Phagocytic Dysfunction - Primary Immunodeficiencies

Primary Immunodeficiencies

Primary

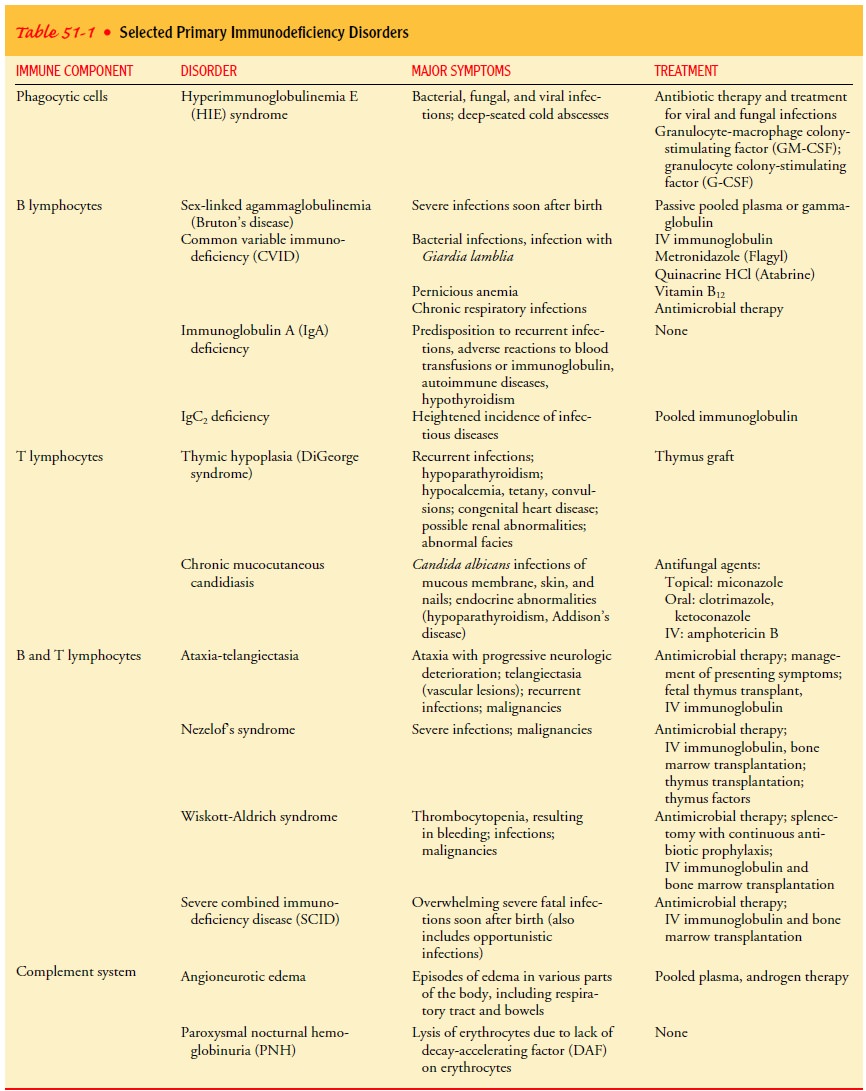

immunodeficiencies, rare disorders with genetic origins, are seen primarily in

infants and young children. To date, more than 95 immunodeficiencies of genetic

origin have been identi-fied (Buckley, 2000). Symptoms usually develop early in

life after protection from maternal antibodies decreases. Without treat-ment,

infants and children with these disorders seldom survive to adulthood. These

disorders may involve one or more components of the immune system. Symptoms of

immune deficiency diseases are related to the role that the deficient component

normally plays (Table 51-1).

PHAGOCYTIC

DYSFUNCTION

Pathophysiology

A variety of primary defects of phagocytes

may occur; nearly all of them are genetic in origin and affect the innate

immune system. In some types of phagocytic disorders, the neutrophils are

im-paired so that they cannot exit the circulation and travel to sites of

infection. As a result the patient cannot mount a normal inflam-matory response

against pathogenic organisms (Lekstrom-Himes Gallin, 2002). In some disorders, the

neutrophil count may be very low; in others, it may be very high because the

neutrophils re-main in the vascular system.

Clinical Manifestations

Phagocytic cell disorders are manifested by

an increased incidence of bacterial and fungal infections due to normally

nonpathogenic organisms (Lekstrom-Himes & Gallin, 2002). People with these

disorders may also develop fungal infections from Candida or-ganisms and viral

infections from herpes simplex or herpes zoster virus. These patients

experience recurrent furunculosis, cutaneous abscesses, chronic eczema,

bronchitis, pneumonia, chronic otitis media, and sinusitis. In one type of phagocytic

disorder, hyper-immunoglobulinemia E (HIE) syndrome, formerly known as Job

syndrome, white blood cells cannot produce an inflammatory re-sponse to the

skin infections; this results in deep-seated cold ab-scesses that lack the

classic signs and symptoms of inflammation (redness, heat, and pain).

While patients with phagocytic cell disorders

may be asympto-matic, severe neutropenia may be accompanied by deep and painful

mouth ulcers, gingivitis, stomatitis, and cellulitis. Death from overwhelming infection

occurs in about 10% of patients with severe neutropenia. Chronic granulomatous

disease, another type of primary phagocytic disorder, produces recurrent or

persistent infections of the soft tissues, lungs, and other organs; these are

re-sistant to aggressive treatment with antibiotics (Lekstrom-Himes &

Gallin, 2002).

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

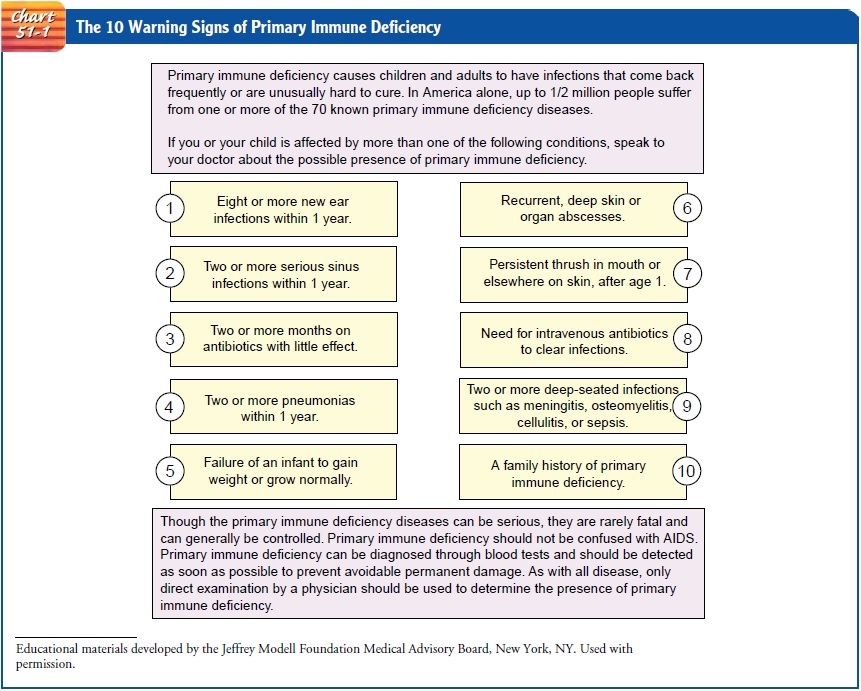

Diagnosis is based on the history, signs and

symptoms, and lab-oratory analysis of the cytocidal (causing the death of

cells) activ-ity of the phagocytic cells by the nitroblue tetrazolium reductase

test. A history of recurrent infection and fever in a child and occasionally in

an adult is an important key to the diagnosis. Failure of an infection to

resolve with usual treatment is also an important indicator (Lekstrom-Himes

& Gallin, 2002). See Chart 51-1 for a summary of warning signs of primary

immunodeficiency disorders.

Medical Management

Because the signs and symptoms of infection are often blunted because of an impaired inflammatory response, early diagnosis and treatment of infectious complications can be lifesaving (Lekstrom-Himes & Gallin, 2002). Management of phagocytic cell disorders includes treating bacterial infections with prophy-lactic antibiotic therapy. Additional treatment for fungal and viral infections is often needed. Granulocyte transfusions, although used, are seldom successful because of the short half-life of the cells. Treatment with granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) or granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) may prove successful because these proteins draw nonlymphoid stem cells from the bone marrow and hasten their maturation.

Related Topics