Chapter: Medical Microbiology: An Introduction to Infectious Diseases: Middle and Lower Respiratory Tract Infections

Middle Respiratory Tract Infection

MIDDLE RESPIRATORY TRACT INFECTION

For the purpose of this discussion, the middle respiratory tract is considered to comprise the epiglottis, surrounding aryepiglottic tissues, larynx, trachea, and bronchi. Inflamma-tory disease involving these sites may be localized (eg, laryngitis) or more widespread (eg, laryngotracheobronchitis). The majority of severe infections occur in infancy and childhood. Disease expression varies somewhat with age, partly because the diameters of the airways enlarge with maturation and because immunity to common infectious agents increases with age. For example, an adult with a viral infection of the larynx (laryngitis) who was exposed to the same virus in childhood has a relatively better immune response; in addition, the larger diameter of the larynx in the adult permits greater air flow in the presence of inflammation. An infant or child with the same infection in the same site can develop a much more severe illness, known as croup, which can lead to significant ob-struction of air flow.

CLINICAL FEATURES

Epiglottitis is often characterized by the abrupt onset of throat and neck pain, fever, andinspiratory stridor (difficulty in moving adequate amounts of air through the larynx). Because of the inflammation and edema in the epiglottis and other soft tissues above the vocal cords (supraglottic area), phonation becomes difficult (muffled phonation or apho-nia), and the associated pain leads to difficulty in swallowing. If this disease is not treated promptly, death may result from acute airway obstruction.

Laryngitis or its more severe form, croup, may have an abrupt onset (spasmodic croup) or develop more slowly over hours or a few days as a result of spread of infection from the upper respiratory tract. The illness is characterized by variable fever; inspiratory stridor; hoarse phonation; and a harsh, barking cough. In contrast to epiglottitis, the in-flammation is localized to the subglottic laryngeal structures, including the vocal cords. It sometimes extends to the trachea (laryngotracheitis) and bronchi (laryngotracheobronchi-tis), where it is associated with a deeper, more severe cough that may provoke chest pain and variable degrees of sputum production. When vocal cord inflammation is severe, transient aphonia may result.

Bronchitis or tracheobronchitis may be a primary manifestation of infection or a re-sult of spread from upper respiratory tissues. It is characterized by cough, variable fever, and sputum production, which is often clear at the onset but may become purulent as the illness persists. Auscultation of the chest with the stethoscope often reveals coarse bub-bling rhonchi, which are a result of inflammation and increased fluid production in the larger airways.

Chronic bronchitis is a result of long-standing damage to the bronchial epithelium. Acommon cause is cigarette smoking, but a variety of environmental pollutants, chronic in-fections (eg, tuberculosis), and defects that hinder normal clearance of tracheobronchial secretions and bacteria (eg, cystic fibrosis) can be responsible. Because of the lack of func-tional integrity of their large airways, such patients are susceptible to chronic infection with members of the oropharyngeal flora and to recurrent, acute flare-ups of symptoms when they become colonized and infected by viruses and bacteria, particularly Streptococ-cus pneumoniae and nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae. A vicious cycle of recurrent in-fection may evolve, leading to further damage and increasing susceptibility to pneumonia.

COMMON ETIOLOGIC AGENTS

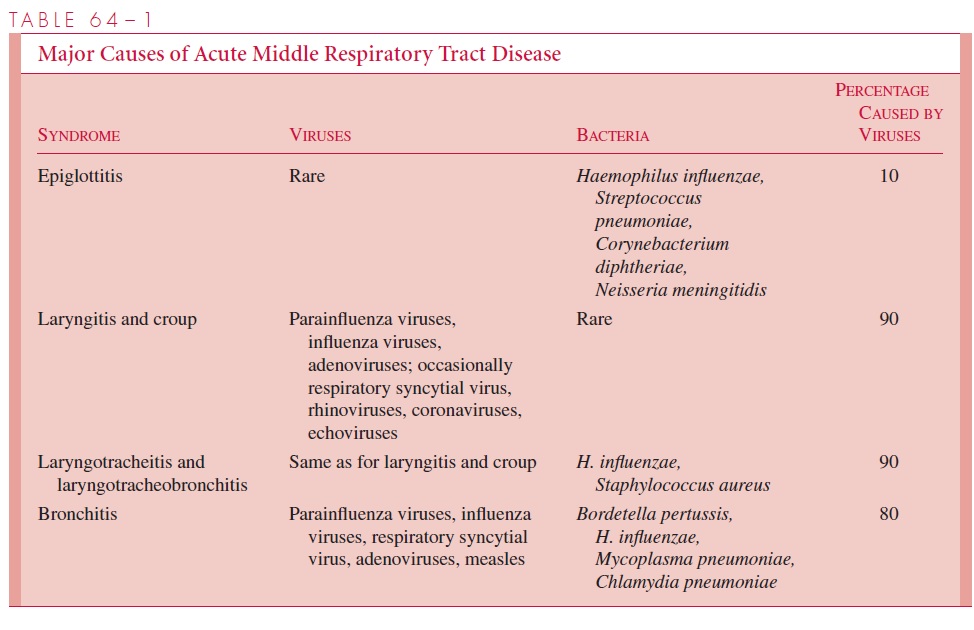

With the exception of epiglottitis, acute diseases of the middle airway are usually caused by viral agents (Table 64 – 1). When acute airway obstruction is present, noninfectious possibilities, such as aspirated foreign bodies and acute laryngospasm or bronchospasm caused by anaphylaxis, must also be considered.

GENERAL DIAGNOSTIC APPROACHES

When a viral etiology is sought, the usual method of obtaining a specific diagnosis is by inoculation of cell cultures with material from the nasopharynx and throat. Acute and convalescent sera can also be collected to determine antibody responses to the common respiratory viruses and Mycoplasma pneumoniae. In bacterial infections, the approaches noted below are valuable.

Epiglottitis

H. influenzae type b, once the most common cause of epiglottitis, produces an associatedbacteremia in 85% of cases or more. Attempts to obtain cultures from the epiglottis or throat may provoke acute reflex airway obstruction in patients who have not undergone intubation to ensure proper ventilation; furthermore, the yield is lower than that of blood culture. In addition, other bacterial agents that cause epiglottitis can often be isolated from the blood. The exception is Corynebacterium diphtheriaeinfection, in which cul-tures of the nasopharynx or pharynx are required.

Laryngotracheitis and Laryngotracheobronchitis

Although most cases of laryngotracheitis and laryngotracheobronchitis have a viral etiol-ogy, a severe purulent process is seen occasionally. The latter is often referred to as acute bacterial tracheitis, and it can be rapidly fatal if not managed aggressively. Gram stain-ing and culture of sputum, or better yet, of purulent secretions obtained by direct laryn-goscopy, help establish the causative agent. Blood cultures are again useful in such cases when a bacterial etiology is suspected.

Acute Bronchitis

A major bacteriologic consideration in acute bronchitis, especially in infants and preschool children, is Bordetella pertussis. Deep nasopharyngeal cultures plated on the appropriate media constitute the best specimens. Gram staining and examination of na-sopharyngeal smears by direct fluorescent antibody methods are also useful adjuncts to establishing the diagnosis. When purulent sputum is produced, Gram staining and culture may be useful in suggesting other bacterial causes (see Table 64 – 1). Exceptions include M. pneumoniae and Chlamydia pneumoniae infections, which are usually diagnosed byserologic testing of acute and convalescent sera.

GENERAL PRINCIPLES OF MANAGEMENT

The primary initial concern is ensuring an adequate airway. It is particularly crucial in epiglottitis but can also become a major issue in laryngitis or laryngotracheobronchitis. Thus, some patients require placement of a rigid tube that provides communication between the tracheobronchial tree and the outside air (a nasotracheal tube or a surgically placed tra-cheostomy). Other adjunctive measures, such as highly humidified air and oxygen, may also provide relief in acute diseases involving the structures in and around the larynx. In proved or suspected bacterial infections, specific antimicrobic therapy is required; other treatment, such as antitoxin administration in diphtheria, may also be necessary.

Related Topics