Outbreak of World War II and its Impact in Colonies | History - Liberation Struggles in Indonesia and Philippines | 12th History : Chapter 14 : Outbreak of World War II and its Impact in Colonies

Chapter: 12th History : Chapter 14 : Outbreak of World War II and its Impact in Colonies

Liberation Struggles in Indonesia and Philippines

Liberation Struggles in Indonesia and Philippines

Mao’s victory, following the independence of India,

sent a message that imperialism could be defeated in the colonies. But in

Southeast Asia, especially in the Philippines and Indonesia, nationalism was in

its nascent stage and no substantial progress could be made towards achieving

self-government until the dawn of the 20th century. Three and a half years of

Japanese occupation resulted in the loss of prestige to the European colonial

powers, with the national movements emerging strong and powerful. But after the

defeat of Japan in 1945, Western powers sought to return to their territories.

At first they tried to return as colonial rulers, but a brief period of rule

proved that this to be unrealistic. This resulted in the Dutch and American

attempts to hand over power to friendly, moderate nationalist regimes that

could block the rise of communism which was ascendant after the end of the

World War.

The East Indies (Indonesia)

The Dutch had occupied Java and Sumatra since about

1640. In the second half of the nineteenth century they conquered the outer

islands of the East Indies. During the nineteenth century the Dutch were mainly

interested in economic, not political control. Most of the population relied on

fishing and agriculture. Many worked on European sugar, tobacco, tea and coffee

plantations. Heavy investment in these plantations and other concerns with the

discovery of oil (1900) and the resultant growth of exports and import all made

this area a valuable colony for the Dutch.

The nationalist movement in East Indies took shape

much later than in the Philippines. This is because the Dutch were slow in

introducing Western education. In the Philippines the Eurasians identified

themselves with the native cause and became the leaders of the nationalist

movement. The Dutch, in contrast, largely free of racial prejudice,

intermarried with the natives and accepted the Eurasians in their society. The

Eurasians considered their interests as those of the Dutch.

Rise of Nationalism

The first clear manifestation of nationalism in the

East Indies was in 1908, when the first native political society Boedi Oetomo (High Endeavour) was

organised. The society was founded by students of the first Dutch medical

school at the instance of their senior Wahidin Sudirohusodo. The idea was that

the native intellectuals should take the lead in working for the educational

advancement of the country. It turned out to be a cultural body, consisting

mainly of civil servants and students from Java. Boedi Oetomo soon became defunct and a more popular political society Sarekat

Islam (Muslim Union) emerged.

Sarekat Islam was formed mainly to fight against

the economic power of the Chinese. But it gradually became a socialist and

nationalist body. In 1916 it passed a resolution demanding self-government. In

two years its membership increased from 350,000 to two and a half million.

Encouraged by the Russian Revolution of 1917 the communists within Sarekat

Islam attempted to gain control of the movement. As they failed, they left and

formed the Indonesian Communist Party in 1919.

Party Politics

Efforts at delegating powers to the local

governments had already been initiated with the passage of a Decentralisation

Law in 1903. Provincial councils were established in the following year. But

the Indonesians played no part in the government. In view of the growing

nationalist agitation the Dutch government created a People’s Parliament, Volksraad (1918) in Weltevreden, Batavia

(Jakarta), Java, and this continued to function until 1942.

During the 1920s, the Communists and Sarekat Islam

vied with each other in dominating the nationalist movement. In this rivalry

for leadership the communists were successful. They organised strikes which

culminated in a big uprising in 1926–27 in western Java and Sumatra. This was

immediately crushed. Thousands were imprisoned and this caused a temporary

setback to the Communist Party. Around this time a young engineer named Sukarno

organised the Indonesian Nationalist Party. This third party in the country was

supported by the westernised secular middle class. But in 1931 the police

raided the headquarters of this party. Sukarno was imprisoned and the party he

founded was dissolved.

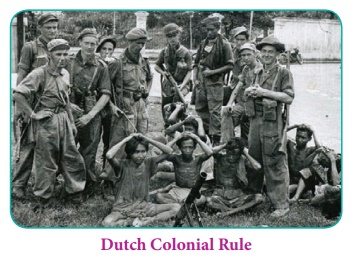

Dutch Repression and Japanese Aggression

During the 1930s, in the wake of the economic

depression that resulted in unemployment, wage cuts and increased protests, the

government resorted to repression and press censorship to check nationalism.

Sukarno and other nationalist leaders were languishing in jail until 1942. The

Dutch surrendered

to the Japanese in the East Indies in March 1942. Some opposed the Japanese and

organised secret resistance. Some led by Sukarno and Hatta believed that the

best method of achieving independence would be to support the Japanese. In the

last phase of the war the Japanese decided to negotiate the terms of

independence with the Indonesian leaders.

Coming of Independence

But after Japanese evacuation, in accordance with

the decisions of the Potsdam Conference, British forces landed in the East

Indies in September 1945. They released about 200,000 prisoners of war, mainly

Dutch. The Dutch had reoccupied nearly all the East Indian islands except Java

and Sumatra, ruled by Sukarno. The Dutch refused to recognise the rule of

Sukarno. Yet he refused to relinquish his office as President. So the

British-occupying force arranged negotiations which led to Dutch-Indonesian

Agreement. This resulted in Dutch recognition of Java and Sumatra as an

independent republic, leading to the merger of the rest of the islands to form

a federation known as the United States of Indonesia. Subsequently, the Dutch

attempted to disrupt the peace in Indonesia twice, but the pressure of world

opinion, led by Jawaharlal Nehru as well as the UN Security Council, led to a

settlement favourable to Indonesia at the end of 1949. A round table conference

held at The Hague adopted a constitution for the independent state of

Indonesia. In December 1949 Indonesia became an independent state.

The Philippines

About 7000 islands named after the Spanish prince

Philip, son of King Charles V, came to form the Philippines. Like the East

Indies, the Philippines had experienced European rule since the sixteenth

century. Spanish colonisation began with the expedition of Miguel Lopez de

Legazpi in February 1565. Following this, Spain ruled the Philippines for over

300 years, imposing its language, culture and religion on the local population.

Nationalism developed among the Filipinos earlier than elsewhere. The brutal

way by which the Cavite uprising (20 January 1872), involving 200 Filipino

troops and workers at the Cavite arsenal, was crushed served to promote the

nationalist cause. A number of Filipino intellectuals were arrested and after a

brief trial, three priests (Jose Burgos, Jacinto Zamora, and Mariano Gomez)

were publicly executed and became martyrs.

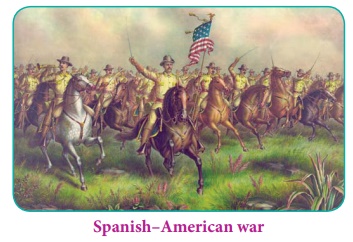

The dispute between America and Spain arising out

of America’s interest in Cuba snowballed into the Spanish–American war. In view

of the mounting pressure building up internally, Spain had already decided to

grant Cuba limited powers of self-government. But the U.S. Congress demanded

the withdrawal of Spain’s armed forces forthwith from the island. The Congress

authorised the use of force to secure that withdrawal. As Spain dodged, the

U.S. declared war on 25 April 1898. Spain had readied neither its army nor its

navy for a distant war with the formidable power of the United States. So it

was an easy victory for the US. By the Treaty of Paris (signed on 10 December

1898), Spain renounced all claim to Cuba, ceded Guam and Puerto Rico to the

United States, and transferred sovereignty over the Philippines to the United

States.

Aguinaldo and other Cavite rebels, while fighting

the Spanish army, won major victories in many battles, driving the Spanish out.

On May 28, 1898, Aguinaldo gathered a orce of about 18,000 troops and fought

against a small Spanish garrison in Alapan, Imus, Cavite. After the victory at

Alapan, Aguinaldo unfurled the Philippine flag for the first time, and hoisted

it at the Teatro Caviteño in Cavite Nuevo (present-day Cavite City) in front of

Filipino revolutionaries and more than 300 captured Spanish troops. Emilio

Aguinaldo was elected the first president of the new republic with the

proclamation of Malolos Constitution. The Philippine Republic endured until the

capture of Emilio Aguinaldo by the American forces on March 23, 1901 that

resulted in the dissolution of the First Republic.

The nationalists of Philippines thought the issue

for America was Cuba. But soon found out that they had only exchanged one

master for another. Frustrated by the outcome of Spanish-American War they

resorted to guerrilla warfare. The nationalist opposition to the American

government was encouraged by a lobby in the US and so the government felt

obliged to create representative institutions at an early date. In the wake of

American rule (1902), most of the primary colonial institutions were firmly

established: an English language education system; an examination-based civil

service; a judicial system with provincial courts; a system of municipal and

provincial governments based on election, and finally an elected national

legislature. In the election held for the 80-member Assembly, the Nationalist

Party won a majority.

The Nationalist Party, however, continued to demand

self-government. The leader of the party, Quezon, said, ‘We should prefer to

rule ourselves in Hell to being ruled by others in Heaven.’ In the 1930s,

during the Depression years, there were serious left-wing risings. The Partido

Komunista ng Pilipinas (PKP) founded in 1930 was declared illegal by the U.S.

colonial authorities. Yet the communist pressure persuaded the United States

government to agree to internal self-government.

The Partido Komunista ng Pilipinas (The Communist Party of the

Philippines) and the Huk Rebellion: Though outlawed by the American government, the Partido Komunista ng Pilipinas regained its legality later and was at the helm of the Hukbalahap, the People’s Army

against the Japanese Aggression. Hukbalahap was a strong guerrilla organisation

and with the re-conquest of the Philippines by the returning American forces,

the PKP and the communist peasants (known as Huks) found themselves under

attack by their presumed wartime allies. Huk areas were bombarded by government

forces and, as a result, the PKP resorted to guerrilla warfare. At first they

adopted it as a defensive posture. But in 1950 the party adopted a strategy for

the seizure of power. By the mid-1950s, however, the “Huk rebellion” had been

crushed by the Philippine government, assisted by the U.S.

In 1934, the Tydings–McDuffie Act (The Philippines

Independence Act) provided a ten year period for transferring power to Filipinos.

During this period the United States could maintain military bases in the

Philippines, and control foreign policy. This Act was ratified by a plebiscite

in 1935. From 1935 to 1941 Quezon was President of the Philippines. Immediately

after the Pearl Harbour attack, Japan attacked the Philippines. The conquest of

the Philippines by Japan is often considered the worst military defeat in

United States history. About 23,000 American military personnel were killed or

captured, while Filipino soldiers killed or captured totalled around 100,000.

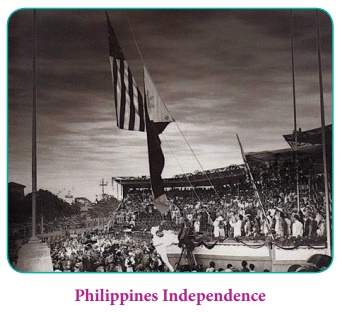

After ending the aggression of Japan, the US

honoured its promise given in the Act. In April 1946 elections were held, and

on 4 July the Philippines became independent. USA left the Philippines but

provided military training and financial support against Huks between 1946 and

1954. Throughout the period the country was one of the USA’s most loyal allies.

The country was one of only three Asian states to join the US-dominated South

East Asian Treaty Organisation (SEATO) in 1954.

Related Topics