Chapter: Information Architecture on the World Wide Web : Production and Operations

Learning from Users

Learning from Users

Unfortunately, many sites fall victim to the

launch ‘em and leave ‘em attitude of site owners, who turn their attention to

more urgent or interesting projects, allowing the content or the architecture

to become obsolete quickly. Even for those sites kept current with respect to

content, the information architectures are rarely refined and extended.

This is too bad, because it is after the

launch of a web site that you have the best opportunity to learn about what

does and doesn't work. If you are fortunate enough to be given the time,

budget, and mandate to learn from users and improve your web site, a number of

tools and techniques can help you do so.

As you read this section, please understand

that high-quality testing of site architectures requires experts in usability

engineering. For pointers to expert coverage of tools and techniques specific

to usability engineering, please review the usability area of our bibliography.

1. Focus Groups

Focus groups are one of the most common and

most abused tools for learning from users. When conducting focus groups, you

gather together groups of people who are actual or potential users of your

site. In a typical focus group session, you may ask a series of scripted

questions about what users would like to see on the site, demonstrate a

prototype or show the site itself, ask questions about the users' perception of

the site, and get their recommendations for improvement.

Focus groups are great for generating ideas

about possible content and function for the site. By getting several people

from your target audiences together and facilitating a brainstorming session,

you can quickly find yourself with a laundry list of suggestions.

However, focus groups are very poor vehicles

for testing the usability of a site. A public demonstration does not come close

to replicating the actual environment of a user navigating a web site.

Consequently, the suggestions of people in focus groups do not necessarily

carry much weight. Sadly, focus groups are often used to prove that a

particular approach does or doesn't work. Through the skillful selection and

phrasing of questions, focus groups can easily be influenced in one direction

or another. To learn more about when and how to conduct focus groups, see the

usability section of our bibliography.

2. Individual User Testing

A much more appropriate way to study the

usability of a prototype or post-launch web site is to conduct individual user

testing. This method involves bringing in some real users, giving them some

typical test tasks, and asking them to think out loud while they perform the

tasks. The statements and actions of the user can be recorded several ways,

ranging from the high-tech videotape and usage tracking approach to the

low-tech notes-on-paper approach. Either way, it's important to try this

exercise with several different users, ideally from different audience groups.

As Jakob Nielsen suggests in "Guerrilla HCI" (http://www.useit.com/papers/guerilla_hci.html ), you can learn a great deal about what does and doesn't work very

quickly and inexpensively using this approach.

3. Questions and Suggestions

One of the simplest ways to collect

information about the usability of your site is to ask users to tell you what

does and doesn't work. Build a Questions and Suggestions area in your site, and

make it available from every page in the site.

In addition, you should adopt a No Dead-Ends

policy, always giving the user a way to move towards the information they need.

One technique involves using the following context-sensitive suggestion at the

bottom of a search results page.:

Not

finding what you're looking for with search? Try browsing our web site or tell

us what you're looking for and we'll try to help.

Whether employing a generic or

context-sensitive approach, make it easy for users to provide feedback. Instead

of using a mailto: tag that requires proper browser customization, use a form-based approach

that integrates online documentation with the opportunity to interact. In this

way, you might answer the user's question faster and avoid spending staff time

on producing the answer.

Avoid the temptation of creating a feedback

form that is long, since most users will never fill it out. Ask only the most

important and necessary questions. If your site is blessed with an active

audience willing to provide feedback, wonderful. If not, you might combine an

online survey with a contest involving free gifts.

Finally, if you're going to make it easy for

users to ask questions and make suggestions, you also need to establish

procedures that allow you to respond quickly and effectively.

It's important to respond to users who take

the time to provide feedback. This is common courtesy. It also makes sense

since a user may be a customer or investor, or perhaps a senior executive in

virtual disguise.

To facilitate prompt responses and promote

efficiency at the back-end, build triage into your site's feedback system.

Provide users with the option to contact the webmaster for technical problems

and the content specialist for questions about the site's content.

You'll also need to create a system for

reviewing and acting upon questions and suggestions. In a large organization,

you may need to form a site review and design committee to meet once per month,

review the questions and suggestions, and identify opportunities for

improvement.

4. Usage Tracking

Basic usage logs and statistics reports are of

little value. They do tell you roughly how many times your site is visited and

which pages are viewed. However, this information does not tell you how to

improve your site.

If you want more useful information, you can

use more complex approaches to tracking users. The most complex approach

involves the tracking of user's paths as they search and browse a web site. You

can trace where a user comes from (originating site) to reach your site; the

path they take through your organization, navigation, and searching systems;

and where they go next (destination site). Along the way, you can learn how

long they spend on each page. This creates a tremendously rich data stream,

which can be fascinating to review, but difficult to act upon. What you need to

make this information valuable is feedback from users explaining why they came

to the site, what they found, and why they left. If you combine technology that

pops up a questionnaire when users are about to leave the site with an

incentive for completing your questionnaire, you might be able to capture this

information. Just be careful not to irritate the users with this kind of

approach. It may be something you do for a short period of time in conjunction

with a special promotion.

A simpler approach involves the tracking and

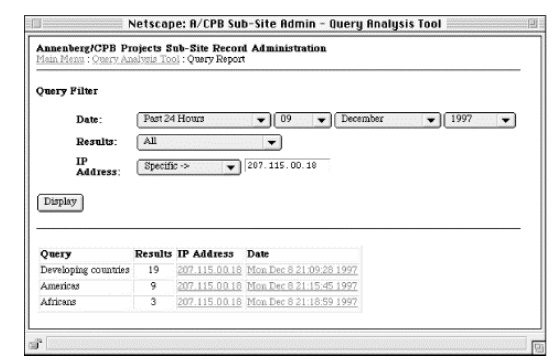

analysis of queries entered into the search engine, like that shown in Figure 9.7. By studying these queries, you can

identify what users are looking for and the words and phrases they use. You can

isolate the queries that retrieve zero results. Are users employing different

labels or looking for information that doesn't exist on your site? Are they failing

to use Boolean operators the way you intended? Based upon the answers, you can

take immediate and concrete steps to fix the problems. You may change labels,

improve search tips, or even add content to the site.

Figure 9.7. This query analysis tool allows you to filter by

date and IP address. You can also isolate queries that resulted in zero hits.

By leveraging the IP address and date/time information, the software enables

you to see an individual user's progress (or lack thereof) as he or she tries

one search after another.

In considering these approaches, it's

important to realize that the data is useful only if you and your organization

are committed to acting upon what you learn. Gigabytes upon gigabytes of usage

statistics are ignored every day by well-meaning but very busy site architects

and designers who fail to close the feedback loop.

However, if you can commit to continuous

user-centric improvement, your site will soon reach a level of quality and

usability beyond what could have ever been achieved through good architectural

design alone. And it will only get better, as it is subjected to the constant

evolutionary pressures of time, competition, and increasingly demanding users.

Similarly, if you maintain that personal feedback

loop between your experiences as a consumer and your sensibilities as a

producer, your information architectures will continue to improve over time.

Related Topics