Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Psychosocial Rehabilitation

Issues in the Design of Psychosocial Interventions

Issues

in the Design of Psychosocial Interventions

The

potential benefits of psychosocial treatment are often not achieved in the

community due to poor understanding of the spe-cial needs and liabilities of

schizophrenia patients. Five factors need to be taken into account when

implementing psychosocial interventions and evaluating the results: 1) timing

and duration of treatment; 2) individual differences in treatment needs; 3) the

role of the patient in treatment; 4) the limitations imposed by impairments in

information processing; and 5) the need to base interventions on a compensatory

model.

Timing and Duration of Treatment

The APA Practice Guidelines for the Treatment of

Patients with Schizophrenia makes a number of important points that are

germane to rehabilitation programming, not the least of which pertains to the

need for multimodal, long-term care: “Schizophrenia is a chronic condition that

frequently has devastating effects on many aspects of the patient’s life and

carries a high risk of suicide and other life-threatening conditions. The care

of most patients involves multiple efforts to reduce the frequency and severity

of episodes and to reduce the overall morbidity and mortality of the disorder.

Many patients require comprehensive and continuous care over the course of

their lives with no limits as to duration of treatment”. This guideline is

widely reflected in case management and pharmacotherapy but has not been

adequately addressed in rehabilitation programs.

The role

for psychosocial treatment and rehabilitation in-creases as the patient becomes

more stable and shifts from support and stress reduction to specific

rehabilitation strategies such as social skills training and cognitive rehabilitation.

This three stage model and associated treatment emphasis has good face

validity.

Treatment

planning must be individualized. While this might seem like a given, many

outpatient treatment systems are designed with a one-size-fits-all model, in which most patients are assigned to a

standard set of group treatments paired with case management. This is a

strategy that maximizes dropouts and minimizes effec-tiveness. This is a

population that is difficult to treat effectively under the best of

circumstances. Positive outcomes are likely only if both the content of

treatment and the format of treatment are tai-lored to the individual patient’s

needs and learning capacities.

The

combination of psychosis, thought disorganization and negative symptoms

(especially anergia, apathy and anhedonia) often lead to the false assumption

that patients are not capable of being active participants in their own

treatment. Indeed, many patients seem unmotivated and are noncompliant, but

such seeming disinterest and passivity should not be interpreted as accurate

reflections of the person’s goals and desires or as immutable traits. Negative

symptoms are not always stable, and they may be secondary to demoralization,

psychotic symptoms, medication side effects and other factors that vary over

time (Carpenter et al., 1988;

McGlashan and Fenton, 1992). Paul and Lentz (1977) have shown that even

extremely withdrawn, chronic schizophrenia patients can be motivated by a

systematic incentive program. Similarly, desire to change and inclination to do

the work required for treatment also vary over time in the same way that

motivation to lose weight or quit smoking varies in nonpatient populations.

As

cogently argued by Strauss (1989), schizophrenia pa-tients have an active

“will”. Much of their behavior is goal di-rected and reflects an attempt to

cope with the illness as best they can. Consequently, it is essential to view

the patient as a potentially active partner and involve him or her in goal

setting and treatment planning. Too often, treatments are imposed on patients

by the treatment team and family members, with little consideration of the

patient’s own desires or capacities. It should not be surprising in such

circumstances if the patient fails to adhere to treatment recommendations,

increasing the risk of re-lapse and creating tensions in relationships with

family members and treatment providers. To be sure, engaging the patient to

es-tablish treatment goals can be a long, arduous process, but failure to do so

courts the larger risk of undermining the very purpose of the intervention.

Impairments in Information Processing

It is now

well established that impaired information process-ing represents one of the

most significant areas of dysfunction in schizophrenia. The illness is marked

by neuropsychological deficits in multiple domains, including verbal memory,

work-ing memory, attention, speed of processing, abstract reasoning and

sensorimotor integration (Braff, 1991; Green and Nuech-terlein, 1999). These

deficits are highly related to social func-tioning and role performance in the

community, as well as to performance in skills training programs (Green, 1996;

Green et al., 2000).

A related

issue concerns the impact of neurocognitive defi-cits on the generalization of

treatment effects. A basic assumption of all psychotherapies is that skills

acquired in treatment sessions must be transferred or generalized to the

patient’s natural envi-ronment. Yet, such generalization is contingent upon

cognitive processes that are often disrupted in schizophrenia, especially

“executive functions” mediated by the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex

(Weinberger, 1987).

Unfortunately,

clinical rehabilitation programs have lagged behind the experimental literature

in this arena and neu-rocognitive deficits generally are not well addressed in

a system-atic manner.

Adoption of a Compensatory Model

A

rehabilitation model is more appropriate for treatment of most patients with

schizphrenia than the standard treatment model as: 1) it implies a narrower

focus on specific skills and behaviors, and 2) it aims to improve functioning

in specific areas, rather than eliminating or curing an entire condition. As

indicated above, cognitive impairment is a central feature of the disorder,

evident in childhood and progressing sharply with the onset of psychotic

illness. It is reasonable to speculate that the impairments observed in ill

adult patients are at least of two types: 1) those present from early in

development; and 2) those that are related to clinical psychotic illness. The

existence of such early, developmentally based impairments suggest that the

concept of “premorbid” functioning in schizophrenia may no longer be tenable;

rather, there is a prepsychotic period during which there is subtle evidence of

the “morbid” process. Thus, the challenge confronting attempts at cognitive

enhancement may not be restoration of function, but instead may be the

development of critical competencies and strategies for coping with deficits.

Consistent

with this hypothesis, a compensatory approach to treatment may be more

appropriate than the restorative or reparative approach characteristic of most

treatment programs. Cognitive adaptation training (CAT) is a creative

compensatory approach developed by Velligan and colleagues (2000). Case

managers provide patients with home-based, compensatory en-vironmental

strategies to help structure the patient’s living en-vironment which maximizes

the likelihood that she/he can com-plete requisite activities of daily living.

Examples include posting reminders about appointments on the exit door from the

apart-ment, listing items of clothing to be worn on the closet door, and

placing

medications in a location that makes it maximally likely that the patient will

see it and be reminded to take it. Prompts and other environmental aides are

individually tailored to the pa-tients’ level of apathy, disinhibition and

executive dysfunction. CAT can be administered in a time limited fashion, but

may be a lifelong service for severely impaired patients. Velligan and

colleagues found 9-months of CAT to be superior to an atten-tion placebo and

standard outpatient care on positive symptoms, negative symptoms, motivation,

community functioning, global functioning and incidence of rehospitalization.

This is an excel-lent model for compensatory interventions, and warrants

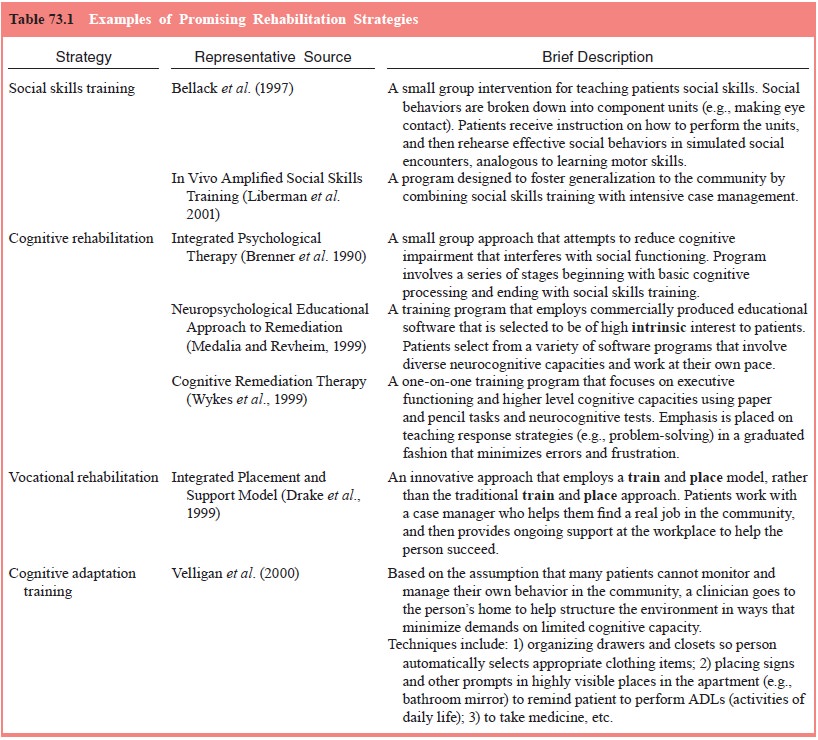

further study (Table 73.1).

Related Topics