Chapter: Medical Microbiology: An Introduction to Infectious Diseases: Vibrio, Campylobacter, and Helicobacter

Helicobacter Gastritis

HELICOBACTER GASTRITIS

Helicobacter infections are limitedto themucosa of thestomach, andmost are asymptomatic even after many years. Burning pain in the upper abdomen, accom- panied by nausea and sometimes vomiting, is a symptom of gastritis. Ulcers may cause additional symptoms, depending on their anatomic location. It is common for gastric and duodenal ulcers to be unrecognized by the patient until they cause.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Infection with H. pylori causes what is perhaps the most prevalent disease in the world. The organism is found in the stomachs of 30 to 50% of adults in developed countries and it is almost universal in developing countries. The exact mode of transmission is not known, but is presumed to be person to person by the fecal – oral route or by contact with gastric secretions in some other way. Colonization increases progressively with age, and children are believed to be the major amplifiers of H. pylori in human populations. A de-clining prevalence in developed countries may be due to decreased transmission because of less crowding and frequent exposure to antimicrobics.

Once established, the same strain persists at least for decades, probably for life. Molec-ular epidemiologic analysis indicates the strains themselves have strong linkages to ethnic origins that can be traced back to the earliest known patterns of human migration. H.pylori hasbeen calledan“accidentaltourist,” which wasestablished in thestomachs of humans before migration began and remained bound to the original population as it dis-persed from continent to continent over thousands of years.

H. pylori is the most common cause of gastritis, gastric ulcer, and duodenal ulcer. Inaddition Helicobacter gastritis caused by Cag+ strains is acknowledged to be the an-tecedent cause of gastric adenocarcinoma, one of the most common causes of cancer death in the world. It is also linked to a gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma, which is less common but shows the striking property of regressing with antimicrobial therapy. H. pylori recently gained the dubious distinction of being the first bacterium declared a class I carcinogen by the World Health Organization.

H. pylori is exclusive to humans, but other species have been found in the stomachs ofa wide range of animals, where they are also associated with gastritis. It is difficult to imagine the old “stress ulcer” theories surviving the discovery of a cheetah with Heli-cobacter gastritis. Speculation that domestic animals may serve as a reservoir for humaninfection has not been confirmed.

PATHOGENESIS

In order to persist in the hostile environs of the stomach, H. pylori employs multiple mechanisms to adhere to the gastric mucosa and survive the acid milieu of the stomach. Motility provided by the flagella allows the organisms to swim to the less acid pH locale beneath the gastric mucus, where the urease further creates a more neutral microenviron-ment by ammonia production. At the mucosa, adherence is mediated by surface proteins, one of which binds to Lewis blood group antigens, often present on the surface of gastric epithelial cells.

H. pylori colonization is virtually always accompanied by a cellular infiltrate rangingfrom minimal mononuclear infiltration of the lamina propria to extensive inflammation with neutrophils, lymphocytes, and microabscess formation. This inflammation may be due to toxic effects of the urease or the VacA. The Cag protein may contribute by stimu-lation of cytokines (interleukin-8), and a neutrophil-activating protein (NAP) has been shown to recruit neutrophils to the gastric mucosa. Added together urease, Cag, and NAP provide ample explanation for the gastritis that is universal in H. pylori infection.

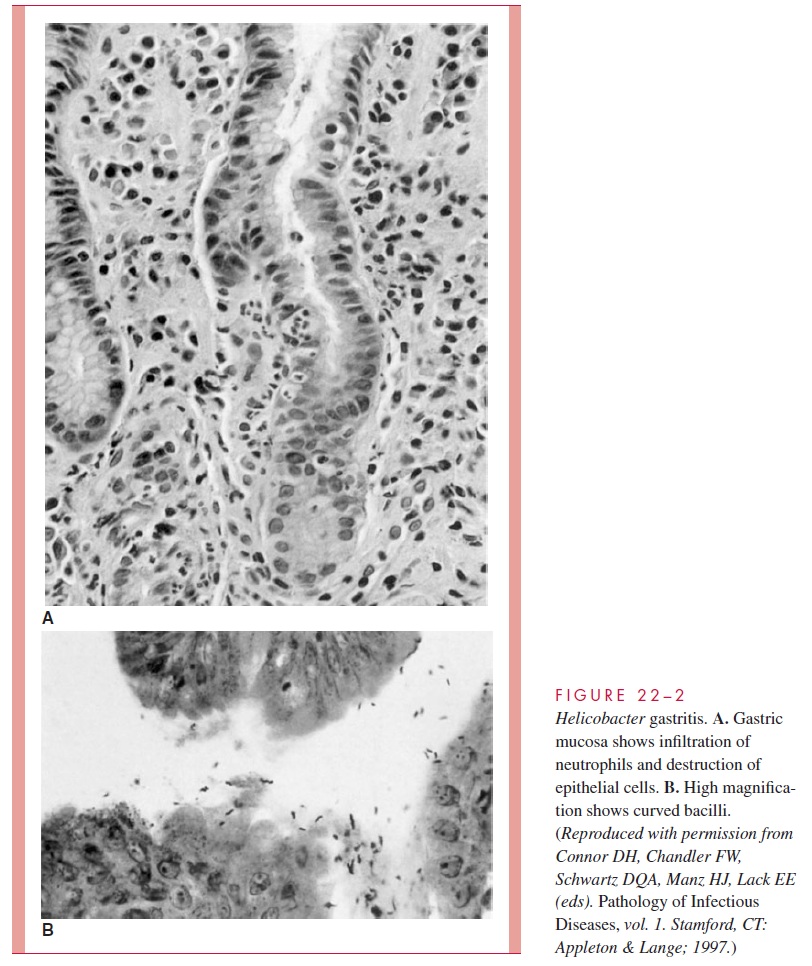

A prolonged and aggressive inflammatory response could lead to epithelial cell death and ulcers, but other virulence factors play a more direct role. The chief of these is VacA, which is responsible for much of the epithelial cell erosion seen in human infec-tion. The vacuolar degeneration it induces is readily visible histologically in gastric biopsies (Fig 22 – 2). The importance of Cag is clear from its epidemiologic association with ulcers, but its exact role is unclear. When Cag is transported into epithelial cells by the PAI secretion system, it induces an active reorganization of the cellular actin cy-toskeleton and activation of multiple host cell proteins. How these changes are inte-grated to contribute to ulcer formation remains to be demonstrated.

That decades of inflammation and assault by the virulence factors described above could eventually lead to cancer seems logical, but the specific mechanisms of carcinogene-sis are unknown. Cag is a leading candidate. A curious paradox is that while Cag strains are associated with ulcers and adenocarcinoma of the lower stomach, they are associated with a decreased incidence of adenocarcinoma of the upper stomach (cardia) and esopha-gus. Dissection of the many actions Cag has within cells should shed light on these issues.

Related Topics