Chapter: Obstetrics and Gynecology: Gynecological Procedures

Gynecological Procedures

PROCEDURES

Gynecologic procedures include

diagnostic procedures such as biopsy and colposcopy, as well as procedures used

as treatment modalities. Some procedures, such as laparoscopy and hysteroscopy,

can be performed for both diagnosis and treatment and are chosen specifically

for this reason.

Genital Tract Biopsy

Biopsies of the vulva, vagina,

cervix, and endometrium are frequently necessary in gynecology. These

proce-dures are usually comfortably performed in the office; they require

either no anesthesia or local anesthesia.

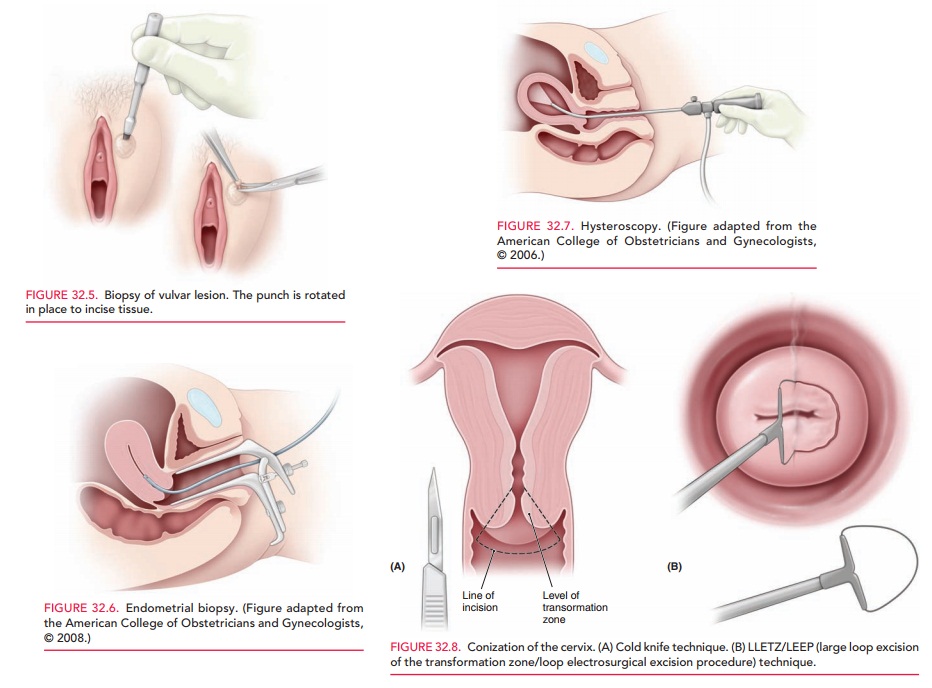

Vulvar biopsies are performed to

evaluate visible lesions, persistent pruritus, burning, or pain. A circular,

hollow metal instrument 3–5 mm in diameter, called a punch, is used to remove a

small disk of tissue for evaluation (Fig. 32.5). For hemostasis, local pressure

or anticoagulants (styptics) such as Monsel solution (ferric subsulfate) or

silver nitrate sticks are often used. Sutures are rarely nec-essary. Local

anesthesia is required for this type of biopsy.

Vaginal biopsy is performed to

assess suspicious masses and to evaluate the vagina in the presence of cervical

abnormalities. Women who have had a prior hysterectomy for cervical cancer

should continue to have Pap tests per-formed on the vaginal cuff; if a result

is abnormal, a vaginal biopsy may be required. Vaginal biopsy is performed with

pinch biopsy forceps. Local anesthesia is rarely required.

Cervical

biopsy is performed with biopsy forcepsand, perhaps, a

colposcope . No anesthesia is necessary. Indications for cervical biopsy

include chronic cervicitis, suspected neoplasm, or ulcer.

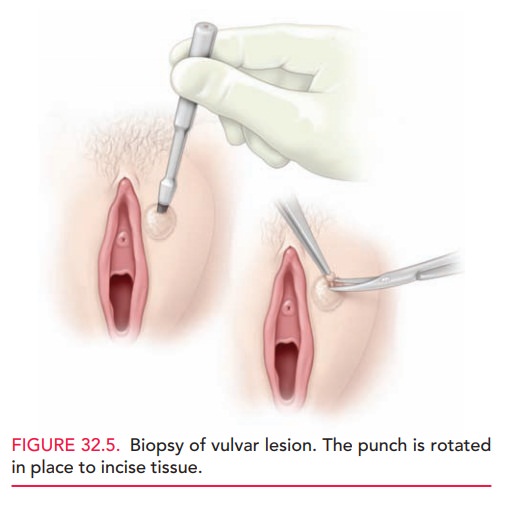

Endometrial

biopsy (EMB) is generally used toevaluate abnormal uterine

bleeding, such as menorrhagia, metrorrhagia, or menometrorrhagia. EMB is

accomplished with a small-diameter catheter with a mild suction mecha-nism

(Fig. 32.6). Various types are available. Anesthesia is not necessary, but many

patients are more tolerant of EMB when given ibuprofen (400–800 mg) 1 hour

prior to the procedure.

Colposcopy

Colposcopy

is performed to evaluate abnormal Pap results.It

facilitates detailed evaluation of the surface of the cervix, vagina, and vulva

when premalignancy or malignancy is suspected based on history, physical

examination, or cytol-ogy. Cervical biopsy of suspicious lesions is frequently

performed during colposcopy.

Cryotherapy

Cryotherapy

is a technique that destroys tissue by freez-ing. A

hollow metal probe (cryoprobe) is placed on the tis-sue to be treated. The

probe is then filled with a refrig-erant gas (nitrous oxide or carbon dioxide)

that causes it to cool to an extremely low temperature (between −65 and −85 degrees C), freezing the

tissue with which the cryoprobe is in contact. Cryotherapy is most often used

to treat cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and other benign lesions such as

condyloma. The formation of ice crystals within the cells of the treated tissue

leads to tissue destruction and subsequent sloughing. Patients who have had

cryotherapy of the cervix can expect to have a watery discharge for several

weeks as the tissues slough and healing occurs. Although cryotherapy is

inexpensive, well-tolerated, and generally effective, it is less precise than

other methods of tissue destruction, such as laser ablation or electrosurgery.

Laser Vaporization

Highly energetic coherent light

beams (light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation [LASER]) may be

directed onto tissues, facilitating tissue destruction or inci-sion, depending

on the specific wavelength of light used and the power density of the beam.

Infrared (CO2) is the most common type of laser used in gynecologic

pro-cedures. Yttrium-aluminum-garnet (YAG), argon, or

potassium-titanyl-phosphate (KTP) lasers, all of which have different effects

on tissues, are also used. Some can be used in the presence of saline or water.

The type of laser is selected according to the indication or desired effect of

the surgery. Although expensive, the great pre-cision that laser offers makes

it a useful tool in specific clinical settings.

Laser therapy is used to treat vaginal and vulvar lesions, such as condyloma, vaginal intraepithelial neopla-sia (VAIN), and vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN). Laser is also used to treat other dermatologic vulvar dis-orders, including molluscum contagiosum and lichen scle-rosis atrophia. Prior to the development of LEEP , laser ablation and conization were common treat-ment modalities for cervical epithelial neoplasia ablation and cervical conization.

Dilation and Curettage

Dilation

and curettage (D&C) is a procedure in which the cervix is dilated using a

series of graduated dilators, followed by curettage (scraping) of the

endometrium, for both diagnos-tic (histologic) and therapeutic reasons. D&C

usually is per-formed under anesthesia in the operating room. Some common

indications for D&C include abnormal uterine bleeding, incomplete or missed

abortion, inability to per-form EMB in the office, postmenopausal bleeding, and

sus-pected endometrial polyp(s). With the availability of newer imaging

procedures, D&C is now less commonly performed.

Hysteroscopy

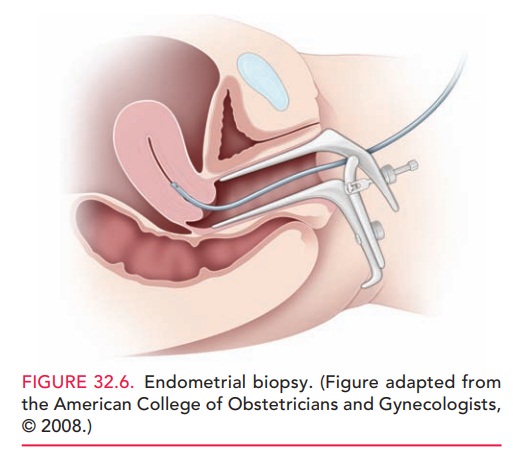

Hysteroscopy is the visualization

of the endometrial cavity using a narrow telescope-like device (Fig. 32.7)

attached to a light source, camera, and distension medium (often normal

saline). It is used to view lesions such as polyps, intrauterine adhesions

(synechiae), septa, and submu-cous myomas. Special instruments allow directed

resec-tion of such abnormalities. Hysteroscopy is commonly performed in the

outpatient setting under general anes-thesia; however, it can also be performed

in the office as a diagnostic procedure or in conjunction with either

endometrial ablation or sonohysterography.

A procedure for nonreversible

sterilization has been designed to be used in conjunction with the

hysteroscope. In this procedure, metal coils are inserted into the ostium of

each fallopian tube under direct visualization. Scarring of the tubal ostia

then occurs. To confirm that the tubes are occluded, an HSG must be performed

three months later.

Endometrial Ablation

Endometrial ablation is used to burn away the uterinelining. The procedure is used to treat abnormal uterine bleeding in women who do not wish to become pregnant. It is not a method of sterilization; therefore, women who undergo ablation must use some other form of birth control. Various ablation devices are available; some use heat, and others use cryotherapy. Some, but not all, of the available techniques involve direct visualization of the endometrium with a hysteroscope. Many women opt for endometrial abla-tion because it is a minor procedure, thus avoiding major surgery in the form of a hysterectomy. The procedure can be performed in either the surgical suite or office. In the office, a combination of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, a local anesthetic, and an anxiolytic is used to pro-vide pain relief.

Pregnancy Termination

Pregnancy termination refers to

the planned interruption of pregnancy before viability and is often referred to

as induced abortion. It is generally accomplished surgically through dilation

of the cervix and evacuation of the uterine contents, accomplished under local

anesthesia. In the first and early second trimester, removal of the products of

con-ception uses either a suction or a sharp curette. Suction curettes are

often preferred, because they are less likely to cause uterine damage such as

endometrial scarring or per-foration. In the second trimester, destructive

grasping for-ceps may be used to remove the pregnancy through a dilated cervix

(dilation and evacuation [D&E]).

Alternatively, in the first

trimester (within 9 weeks of the first day of the last menstrual period),

pregnancy can be terminated using medical rather than surgical tech-niques.

Medical abortion may be carried out using one of the following methods:

· Mifepristone

and misoprostol pills

· Mifepristone pills and vaginal misoprostol

· Methotrexate

and vaginal misoprostol

· Vaginal

misoprostol alone

A woman who is still pregnant

after an attempted medical abortion needs to have a surgical abortion.

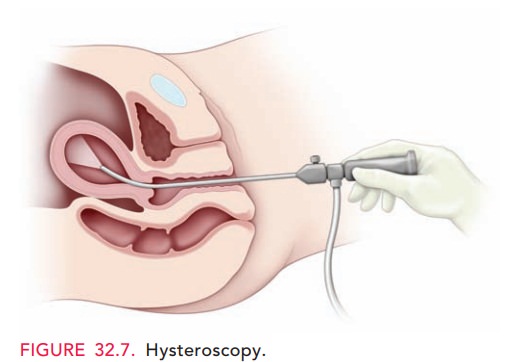

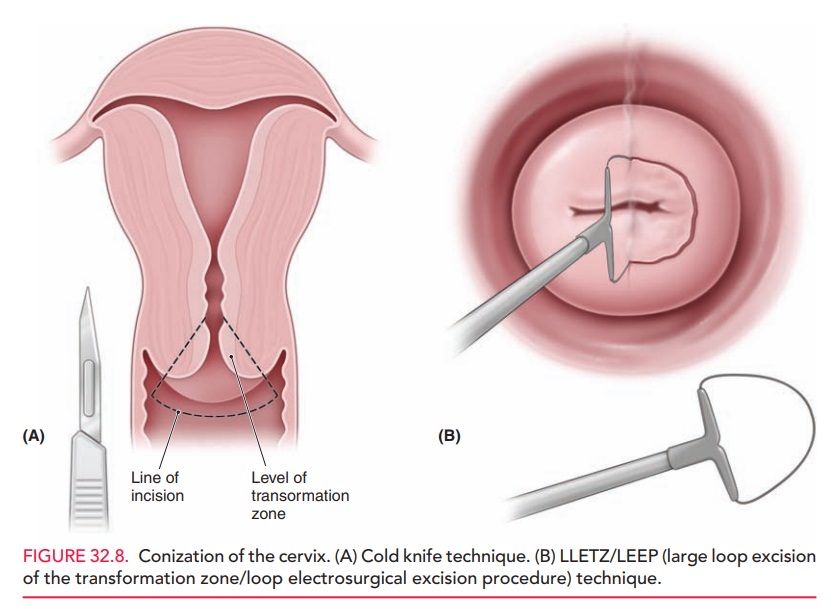

Cervical Conization

Conization is a surgical procedure in which a cone-shaped sample of tissue, encompassing the entire cervical transfor-mation zone and extending up the endocervical canal, is removed from the cervix (Fig. 32.8). It may be required as the definitive diagnostic procedure in the evaluation of an abnormal Pap test when the colposcopic examination is inadequate, or when colposcopic biopsy findings are incon-sistent with Pap test results. Colposcopy-guided conization may also be used therapeutically in cases of cervical intra-epithelial neoplasia (CIN). Various techniques for coniza-tion are available, including cold knife (scalpel), laser excision, or electrosurgery (loop electrosurgical excision procedure [LEEP], also called large loop excision of the transformation zone [LLETZ]). Laser excision and LEEP are often performed in the office. Long-term complications may include cervical insufficiency and stenosis.

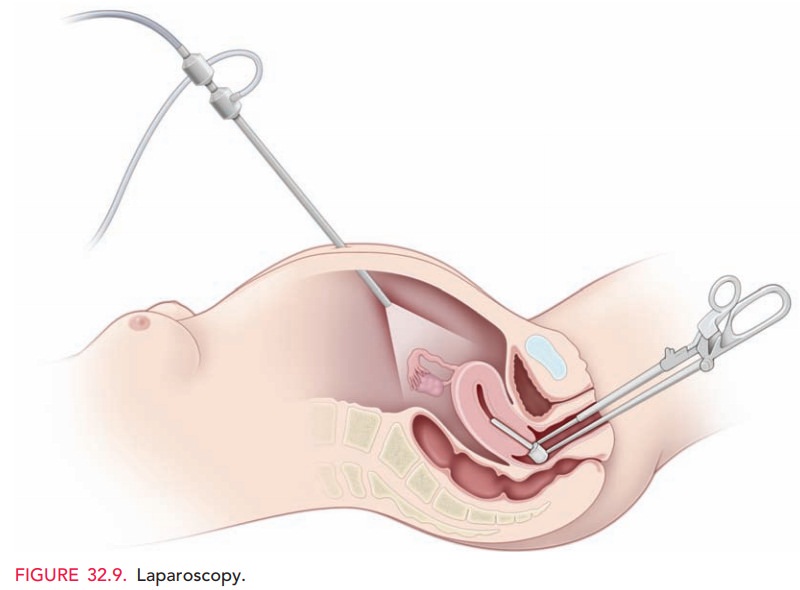

Laparoscopy

Laparoscopy is the visualization of the pelvis and abdomi-nal cavity using an endoscopic telescope, which is most often placed via an incision in the periumbilical region (Fig. 32.9). The procedure may be diagnostic or thera-peutic. Laparoscopic evaluation and treatment may be performed for conditions such as chronic pelvic pain, endometriosis, infertility, pelvic masses, ectopic pregnan-cies, and congenital abnormalities. Sterilization (bilateral tubal ligation) using techniques such as bipolar cautery, clips, or bands can be accomplished easily via laparoscopy.

During the procedure, car-bon dioxide is insufflated to distend

the peritoneal cavity to provide visualization. Additional instruments with

diame-ters of 5–15 mm may be inserted via other laparoscopic incisions. The

number, length, and location of incisions depend on the instruments needed and

the size of any tis-sue specimens that are to be removed. Transvaginal

inser-tion of a uterine manipulator facilitates these maneuvers.

After laparoscopy, the most

common complaints in-clude incisional pain and shoulder pain due to referred

pain of diaphragmatic irritation from the gas used to provide visualization.

Rare, but serious complications include dam-age to major blood vessels, the

bowel, and other intra-abdominal or retroperitoneal structures. However, when

compared with laparotomy, laparoscopy has several advan-tages, including

avoidance of long hospital stays, smaller incisions, quicker recovery, and

decreased pain.

Hysterectomy

Hysterectomy, removal of the

uterus, is still one of the most commonly performed surgical procedures. In the

United States, more than 500,000 hysterectomies are completed annually. The

indications for hysterectomy are numer-ous; they include abnormal uterine

bleeding that has not responded to conservative management, pelvic pain,

post-partum hemorrhage, symptomatic leiomyomas, symptom-atic uterine prolapse,

cervical or uterine cancer, and severe anemia from uterine hemorrhage.

Patients are often confused by inaccurate terms used to describe types of hysterectomy. To many patients, a “complete” hysterectomy means removal of the uterus, fallopian tubes, and ovaries, and a “partial” hysterectomy means removal of the uterus but not the tubes and ovaries. However, the correct term for the removal of both tubes and both ovaries is a bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, and this procedure is generally not part of a hysterectomy. Thus, it is important to determine exactly what procedure a patient may have had. Equally important is what a patient is expecting when a surgical procedure is planned. A total hysterectomy is the removal of the entire uterus, whereas a supracervical (or subtotal) hysterectomy removes the uterine corpus while leaving the cervix. The uterus may be removed by several different routes.

ABDOMINAL HYSTERECTOMY

Abdominal hysterectomy is performed via a laparotomy incision. The laparotomy incision can be either trans-verse, usually Pfannenstiel, or vertical. The decision to perform a laparotomy involves many factors—the skill of the surgeon, the size of the uterus, concern for extensive pathology (e.g., endometriosis or cancer), the need to per-form adjunct surgery during the surgery (e.g., lymph node dissection, appendectomy, omentectomy), and previous intra-abdominal scarring or surgeries.

VAGINAL HYSTERECTOMY

Vaginal hysterectomy is preferred if there is adequate uter-ine mobility (descent of the cervix and uterus toward the introitus), the bony pelvis is of an appropriate configura-tion, the uterus is not too large, and there is no suspected adnexal pathology. In general, vaginal hysterectomy is performed for benign disease. The advantage of vaginal surgery is less pain than with abdominal surgery, quicker return of normal bowel function, and a shorter hospital stay. If indicated, a unilateral or bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy can be performed in conjunction with a vaginal hysterectomy.

LAPAROSCOPIC-ASSISTED VAGINAL HYSTERECTOMY

Laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy (LAVH), with or without a bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, is often performed for patients who desire minimally invasive surgery and may not have adequate descensus of their uterus to undergo a vaginal hysterectomy. LAVH can be accom-plished by performing most or all of the procedure lapa-roscopically; then the uterus is removed through the vagina. The vaginal cuff can then be sutured transvaginally or laparoscopically.

TOTAL LAPAROSCOPIC HYSTERECTOMY

Many skilled laparoscopic

surgeons are now performing a hysterectomy totally via the laparoscopic

approach. This is usually accomplished with the assistance of a morcellator,

which divides the uterus into multiple smaller specimens that can be removed

through the ports. Even large uteri can be safely removed through small

incisions.

Related Topics