Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Time-limited Psychotherapy (Including Interpersonal Therapy)

General Principles of Time-limited Psychotherapy

General

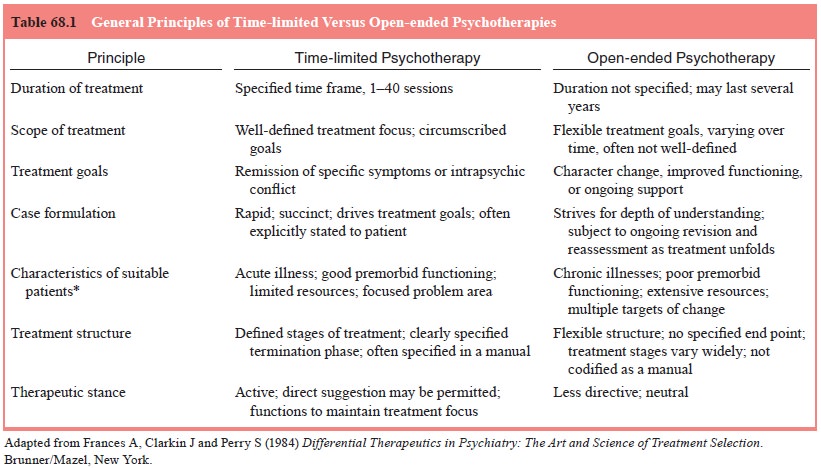

Principles of Time-limited Psychotherapy

The

hallmark of TLP is its specified treatment duration. Because of this

compression, TLPs share attributes that both link them to one another and

distinguish them from long-term treatment mo-dalities. These general principles

are summarized in Table 68.1.

Time Limit

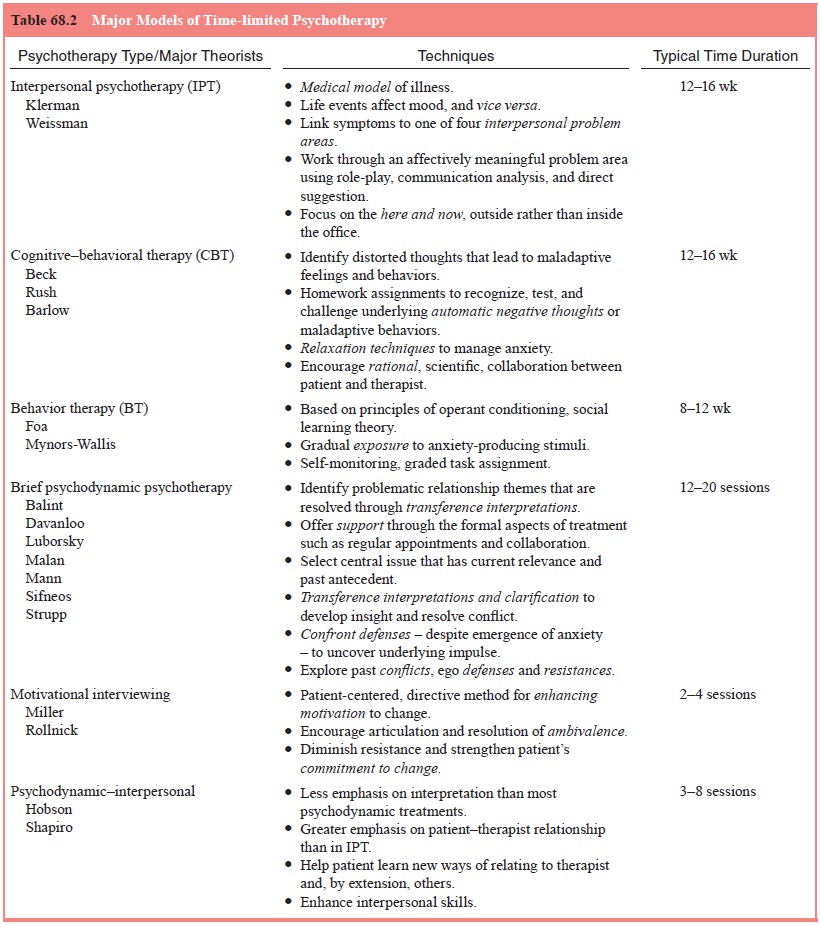

Table

68.2 groups psychotherapies commonly administered in a time-limited format by

treatment approach and lists representa-tive examples of strategies and typical

treatment durations.

TLPs

differ from truncated long-term treatments that are interrupted by attrition,

noncompliance, or the pressures of man-aged care organizations. The duration of

these latter therapies may coincide with that of a TLP, but they do not

constitute fully formed brief treatments. TLPs have distinctly defined

beginnings, middles, and ends – regardless of their absolute duration.

Knowl-edge from the outset that therapy has a defined end-point indeed may

constitute a key active ingredient of time-limited therapy. It suggests that

relief may be near at hand. Marmor speculates that this approach “counters the

patient’s impulse to see him-self as helpless, inadequate, and in need of

dependent support”. Our experience with IPT as a treatment for depression in

individuals who are HIV-seropositive suggests that these individuals, despite

shortened life spans, use the brev-ity of treatment as an impetus to effect

radical, rapid changes in their lives (Swartz and Markowitz, 1998). The time

limit, in a variety of ways, seems to provide an important motivation to speed

the patient toward health.

A meta-analysis

of many psychotherapy studies (none of them TLPs) found that most (75%)

patients achieve symptom relief within 26 sessions of an open-ended treatment

(Howard et al., 1986). Most

treatments included in this meta-analysis were naturalistic (e.g., not controlled) studies of patients suffering

from very heterogeneous symptoms (diagnoses are not specified). This finding

suggests that many patients may respond quickly, even if psychotherapy is

open-ended. Although no studies have com- pared prospectively response rates of

TLPs to open-ended treat-ments, we predict that treatment response would be

more rapid for patients receiving time-limited interventions because of

ex-plicit expectations that therapy will conclude within a specified time

frame. TLPs are generally dosed with a frequency of once a week, although this

varies as well.

The

optimal duration and dosage of TLP, although em-pirical questions, remain

largely unanswered to date. In practice, treatment duration is often defined by

convention, the exigencies of a research protocol or managed care organization,

or even the inclinations of the therapist.

IPT: Duration of Treatment

IPT was

originally designed as a 16-week intervention so that it could be administered

over the same period as an acute course of pharmacotherapy, allowing an

assessment of the relative efficacy of the two interventions (DiMascio et al., 1979). IPT is also administered

as a 14-session intervention (Markowitz unpublished data), a 12-session

intervention (Mufson et al., 1999;

O’Hara et al., 2000) and an

eight-session intervention (Swartz et al.,

2002), but there are no data comparing the relative benefits of varying doses of acute IPT.

Treatment Focus

An

important characteristic of TLP is careful definition of treat-ment goals,

which are usually agreed upon by the patient and therapist, and often specified

at the beginning of treatment. Because therapy is brief, the scope of the

treatment is circum-scribed and focused. TLPs do not attempt sweeping changes

in character. Rather, treatments target a specific diagnosis, set of symptoms,

or a narrow aspect of character. Typical and appro-priate treatment goals for

TLPs include remission of depressive symptoms, reduction in frequency of

binge-eating, and resolu-tion of a specific interpersonal conflict.

Most TLPs

define treatment goals by diagnostic criteria, in much the manner of

pharmacotherapies. IPT focuses on two discrete goals: remission of depressive

symptoms and resolu-tion of an interpersonal problem area (Weissman et al., 2000). Cognitive–behavioral

therapy for panic disorder focuses on reduction in frequency of panic attacks

and relief of general anxiety symptoms (Barlow, 1997). Motivational

interviewing, a brief intervention designed to facilitate behavior change, is

often administered for the sole purpose of helping patients reduce or eliminate

their alcohol consumption (Miller and Rollnick, 1991). Thus, although the

treatments vary in their focus, in all cases their treatment goals are narrow

and usually specified from the outset.

Case Formulation

Treatment

focus is closely allied with the broader concept of case formulation. According

to Eells, psychotherapy case for-mulation is “a hypothesis about the causes,

precipitants, and maintaining influences of a person’s psychological,

interper-sonal, and behavioral problems…. It should serve as a blueprint,

guiding

treatment” (Eells, 1997, pp. 1–2). In TLP, because time is short, the process

of generating a case formulation is also com-pressed. The therapist must

identify the most important compo-nents of the patient’s narrative, balancing

the urge to learn more about the patient’s life circumstances with the time

constraints of the TLP. Thus, the TLP therapist typically conducts an overview

of the patient’s psychosocial circumstances and then selects a few “hot” topics

– relevant both to the current complaint and the nature of the therapy – to

consider in greater depth. This ap-proach allows the therapist to develop an

informed, timely case formulation. The ability rapidly to develop and deliver

such a for-mulation is for many therapists among the more difficult but also

most valuable aspects of learning a TLP.

IPT: Case Formulation

Case

formulation in IPT builds on two core IPT concepts: 1) de-pression is a

treatable illness and 2) events in one’s psychosocial environment affect one’s

mood, and vice versa. The IPT thera-pist defines depression as a medical

illness that, like asthma, is both treatable and affected by the patient’s

circumstances. The therapist notes that, in a biologically vulnerable

individual, when painful events occur, mood worsens and depression may result.

Conversely, depressed mood compromises one’s ability to handle one’s social

role, generally leading to negative events. IPT thera-pists use the connections

among mood, environment and social role to help patients understand their

depressions within an inter-personal context, and to teach them to handle their

social role and environment so as to both solve their interpersonal problems

and relieve their depressive syndrome.

The

therapist’s formulation includes a diagnosis of depres-sion as a medical

illness, the provision of reassurance and hope, the assignment of the sick role

and, most importantly, the identi-fication of one (or at most two)

interpersonal problem areas that become the agenda for the remainder of the

treatment. The thera-pist directly states this case formulation to the patient

and elicits his or her agreement with the proposed strategy before moving ahead

with the next phase of treatment. Thus, in IPT, case for-mulation constitutes

an important treatment tool that links the patient’s mood symptoms to life

events and introduces a specific interpersonal problem area as the focus of

treatment for the ensu-ing sessions (Markowitz and Swartz, 1997).

The

brevity of treatment leaves little room for error in for-mulating the IPT case

– or any TLP case, for that matter. The therapist must use the initial

treatment sessions aggressively to pursue all potential areas and to determine

the treatment focus prior to embarking on the middle phase of treatment. If a

cov-ert and imposing problem area should arise in the middle phase, however,

the therapist would have to renegotiate the treatment contract to address it.

Structured Treatment

In TLP,

the structure of the intervention is clearly delineated and referenced

throughout the treatment period. The therapist will often call the patient’s

attention to important landmarks in the treatment: “Today we’ve reached the

halfway point” or “We only have three sessions left”. In manualized treatments,

each of these time intervals has specified tasks or strategies. For instance,

in IPT, the initial phase can last up to three sessions. During that time, the

therapist has spe-cific tasks (viz., obtain a psychiatric history and

interpersonal inven-tory, offer a case formulation). Similarly, the middle and

end phases of treatment have a specified duration and associated tasks.

In

support of the treatment structure, TLP requires the therapists to make formal

or informal “treatment contracts” in which the patient and therapist explicitly

or implicitly agree to goals, duration and other parameters of treatment. The

thera-pist may discuss with the patient the exact number of sessions planned,

rules for missed sessions or rescheduled sessions, fees and so on. Although

some aspects of treatment contracts are common to all psychotherapies, TLPs

tend to specify more ele-ments in the contract from the outset, including

expected treat-ment responses (e.g., “At the end of 16 weeks, your mood will

likely be much better”) and specific requirements of the patient (e.g.,

homework assignments in Prolonged Exposure and CBT). Patients often find the

transparent structure of TLPs reassuring, removing some of the unnecessary

mystery (and perhaps stigma) historically associated with psychotherapy.

Most TLPs

call for serial assessments of symptoms. In clinical practice (and in clinical

trials), it is often practical to administer a self-report measure such as the

Beck Depression Inventory (Beck and Steer, 1993) or the Beck Anxiety Inventory

(Beck and Steer, 1990). Regardless of the instrument chosen, it is important to

build into the weekly therapy session time to complete and review a

standardized symptom measure and track change over time. Serial symptom

assessment provides the pa-tient with additional psychoeducation (i.e., symptom

recognition) and a reliable means of tracking improvement (or lack thereof).

Active Therapist

In order

to maintain the treatment focus, the therapist must be ac-tive in TLP. He or

she must move the treatment process forward under the pressure of an inexorably

ticking clock. This demands constant attention to the treatment focus and

redirection of the patient if the focus falters. The therapist gently keeps the

patient on task, shaping the treatment rather than simply following the

patient’s lead. A challenge in TLP is to balance strict adherence to the

treatment focus with an empathic stance that supports the treatment alliance.

Although it is important to attend to the agreed upon problem area in IPT, it

is also important that the pa-tient feel “heard” and that the therapist allows

time in the session for the patient to express his or her feelings unimpeded.

Related Topics