Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Factitious Disorders

Factitious Disorders: Treatment and Prognosis

Treatment and Prognosis

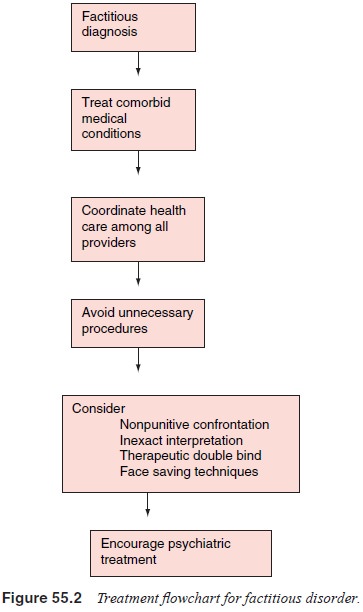

The goals in treating patients with factitious disorder are twofold;

first to minimize the damage done by the disorder to both the patient’s own

health and the health care system. The second goal is to help patients recover,

at least partially, from the disorder. These goals are furthered by treating

comorbid medical illnesses, avoiding unnecessary procedures, encouraging

patients to seek psychiatric treatment and providing support for health care

clini-cians. Because the literature is based exclusively on case reports and

series, determining treatment effectiveness is difficult. As mentioned before,

patients with true Munchausen’s syndrome (including antisocial traits,

pathological lying, wandering and poor social support) are felt to be

refractory to treatment. While factitious disorder is extremely difficult to

cure, effective tech-niques exist to minimize morbidity, and some patients are

able to benefit greatly from psychiatric intervention.

The course of untreated factitious disorder is variable. While patients

with factitious disorder commonly suffer a great deal of morbidity, fatal cases

appear to be less common. One sur-vey of 41 cases noted only one fatality,

though many of the other cases were life-threatening (Reich and Gottfried,

1983). However, patients with psychological signs and symptoms are reported to

have a high rate of suicide and a poor prognosis.

Soon after the widely noted publication of the first arti-cle on

factitious disorders (Asher, 1951) many patients with fac-titious disorder were

vigorously confronted once the nature of their illness was discovered.

Unfortunately, most patients would deny their involvement and seek another

provider who was una-ware of their diagnosis (Eisendrath, 2001). In addition,

the idea of “blacklists” was proposed in order to aid detection of these

pa-tients. However, issues regarding patient confidentiality as well as

concerns about cursory medical evaluations that might miss genuine physical

illness prevented this idea from being adopted. Although aggressive

confrontation is usually unsuccessful, sup-portive, nonpunitive confrontation

may be helpful for some. In one case series, 33 patients were confronted with

the factitious nature of their illness. While only 13 admitted feigning

illness, most of the patients’ illnesses subsequently improved, at least in the

short term (Reich and Gottfried, 1983).

Eisendrath suggested three alternatives to confrontation that he found

effective. First is inexact interpretation, in which the psy-chiatrist

interprets the psychodynamics thought to be underlying the patient’s behavior

without explicitly identifying the factitious behavior. He gave the example of

a patient suspected of having fac-titious disorder who developed septicemia after

her boyfriend pro-posed marriage. The consultant suggested that the patient

might feel a need to punish herself when good things happened to her. She

agreed and, soon after, admitted that she had injected a con-taminant

intravenously (Eisendrath, 2001). The second technique is the therapeutic

double-blind. The physician presents the patient with a new medical

intervention to treat his or her illness. The patient is told that one

possibility is that the patient’s illness has a factitious origin, and that, if

so, the treatment would not be ex-pected to work while, if the illness is

biological, the treatment will work and the patient will improve. The patient

must decide to give up the factitious illness or admit it. A third technique is

to provide the patient with a face-saving way, such as hypnosis or

biofeed-back, of giving up his or her symptoms without admitting that they are

not genuine. Eisendrath (2001) points out that in emergent situ-ations, there

may not be time for nonconfrontational techniques, and more directly

confrontational means may be necessary.

Another important component in the treatment of patients with factitious

disorder is the coordination of health care amongall providers. This allows for

fewer unnecessary interventions, minimizes splitting among the health care

team, and allows the health care team to vent and process the strong emotions

that arise when caring for factitious patients. This decreases both the

negative impact on the providers and the chance that anger will be acted out on

the patient.

There are no clear data supporting the effectiveness of medications in

treating factitious disorder. There is a case report of effective pimozide

treatment in a patient thought to have de-lusional symptoms (Prior and Gordon,

1997), as well as a case report of a factitious patient with comorbid

depression improv-ing when treated with an antidepressant in addition to

intensive psychotherapy.

While many patients with factitious disorder are hesitant to pursue

psychiatric treatment, there are numerous case reports of successful treatment

of the disorder with long-term psycho-therapy. In many of these cases, the

therapy lasted several years, including one patient who received treatment

while imprisoned for over 10 years. Plassman reports a case series of 24

factitious patients. Twelve of these patients accepted psychotherapy and 10

continued with long-term treatment, lasting up to 4½ years. He reports

“significant, or at least marked, improvement” in those 10 patients (Plassmann,

1994b). These case reports support the idea that treatment of patients with

factitious disorder is not im-possible, and these patients can improve.

However, expectations must be realistic as improvement in the disorder itself

can take several years. Techniques that target short-term reduction in the

production of factitious symptoms can be effective more quickly. See Figure

55.2 for a treatment flowchart for factitious disorder.

Related Topics