Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Factitious Disorders

Factitious Disorders: Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis, Epidemiology, Etiology

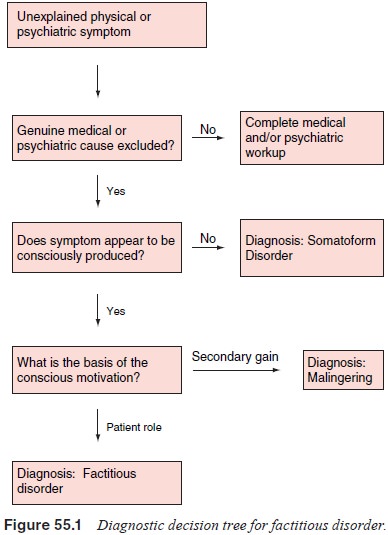

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

The diagnosis of factitious disorder is made in several ways.

Fac-titious disorder is occasionally diagnosed accidentally when the patient is

discovered in the act of creating symptoms. A history of inconsistent or

unexplainable signs and symptoms or failure to respond to appropriate treatment

can prompt health care provid-ers to probe for evidence of the disorder, as can

evidence of per-egrination or pathological lying. In some cases, it is a

diagnosis of exclusion in an otherwise inexplicable case. The differential

diagnosis of factitious disorder includes rare or complex physi-cal illness,

somatoform disorders, malingering, other psychiatric disorders and substance

abuse. It is especially important to rule out genuine physical illness since

patients with factitious disor-der often induce real physical illness.

Furthermore, it is always important to remember the patients with factitious

disorder are certainly not immune to the physical illnesses that plague the

general population.

If there is suspicion of factitious disorder, confirmation can be

difficult. Laboratory examination can confirm some fac-titious diagnoses such

as exogenous insulin or thyroid hormone administration. Collateral information

from family members or previous health care providers can also be extremely

helpful. Factitious disorder with psychological signs and symptoms can

be particularly difficult to diagnose, as so much of psychiat-ric

diagnosis relies on the patient’s report. However, there is some evidence that

neuropsychological testing may be helpful in making the diagnosis. There are

conflicting reports about the ability to detect over 90% of cases of factitious

post traumatic stress disorder using the MMPI. In addition, there is a report

of MMPI test results being used to support a diagnosis of facti-tious disorder

with psychological features in a woman thought to be feigning symptoms of

multiple personality disorder (see Figure 55.1).

Epidemiology

The nature of factitious disorder makes it difficult to determine how

common it is within the population. Patients attempt to conceal themselves,

thereby artificially lowering the prevalence. The tendency of patients to

present several times at different facilities, however, may artificially raise

the prevalence. Most estimates of the prevalence of the disease, therefore,

rely on the number of factitious patients within a given inpatient popula-tion.

Such attempts have generated estimates that 0.5 to 3% of medical and

psychiatric inpatients suffer from factitious disor-der. Of 1288 patients

referred for psychiatric consultation at a Toronto general hospital, 10 (0.8%) were

diagnosed with facti-tious disorder. A prospective examination of all 1538

patients hospitalized in a Berlin neurology department over 5 years found five

(0.3%) cases of factitious disorder. An examination of 506 patients with fever

of unknown origin (FUO) revealed that 2.2% of the fevers were of factitious

origin, and a review of 199 Belgian patients with FUO found seven of 199 (3.5%)

to be factitious. A similar study of patients with FUO at the National

Institutes of Health (NIH) revealed that 9.3% of the fevers were

factitious. The increased prevalence found at the NIH may be due to the fact

that the study was undertaken in a more terti-ary setting, and it is a reminder

that the prevalence of factitious disorder likely varies widely depending on

the population and the setting. Gault and colleagues (1988) examined 3300 renal

stones brought in by patients and found that 2.6% of these stones were mineral

and felt to be submitted by factitious or malin-gering patients. There is much

less data on the prevalence of factitious disorder with psychological features.

A study of psy-chiatric inpatients showed a prevalence of 0.5% of admissions

determined to be a result of a factitious psychological condition. There are

few data about the prevalence of factitious disorder in an outpatient

population. Because factitious patients do not readily identify themselves in

large community surveys, it is not currently possible to determine the

prevalence of the disorder in the general population.

Etiology

Both psychological and biological factors have been postulated to play a

role in the etiology of factitious disorder. Although nu-merous case reports

have generated speculation that factitious disorder may run in families, this

could be explained by environ-mental factors, genetic factors, or both. The

presence of central nervous system (CNS) abnormalities in some patients with

fac-titious disorders have led some to hypothesize that underlying brain

dysfunction contributes to factitious disorder. One review of factitious patients

with pseudologia fantastica found CNS abnormalities (such as EEG abnormality,

head injury, imaging abnormalities, or neurological findings) in 40% of the

patients (King and Ford, 1988). There have been case reports of MRI and SPECT

abnormalities, but it is unknown if these abnormalities were related to the

disorder.

In addition, childhood developmental disturbances are thought to

contribute to factitious disorder. Predisposing fac-tors are thought to include

1) serious childhood illness or ill-ness in a family member during childhood,

especially if the illness was associated with attention and nurturing in an

other-wise distant family, 2) past anger with the medical profession, 3) past

significant relationship with a health care provider, and 4) factitious

disorder in a parent (McKane and Anderson, 1997).

Patients with factitious disorder create illness in pursuit of the sick

role. For these patients, being in the sick role allows them to compensate for

an underlying psychological deficit. Most authors identify several common

psychodynamic motiva-tions for factitious disorder. First, patients with little

sense of self may seek the sick role in order to provide a well-defined

iden-tity around which to structure themselves. Others may seek the sick role

in order to meet dependency needs which have gone unmet elsewhere. As a

patient, they receive the attention, caring and nurturing of the health care

environment and are relieved of many of their responsibilities. In addition,

some patients may engage in factitious behaviors for masochistic reasons. They

feel they deserve punishment for some forbidden feelings and thus they should

suffer at the hands of their physicians. Other patients may be motivated by

anger at physicians and dupe them in re-taliation. Patients with a history of

childhood illness or abuse may attempt to master past traumas by creating a

situation over which they have control. Finally, some authors have speculated

that some patients may be enacting suicidal wishes through their factitious behavior.

Related Topics