Chapter: Obstetrics and Gynecology: Infertility

Evaluation of Infertility

EVALUATION OF INFERTILITY

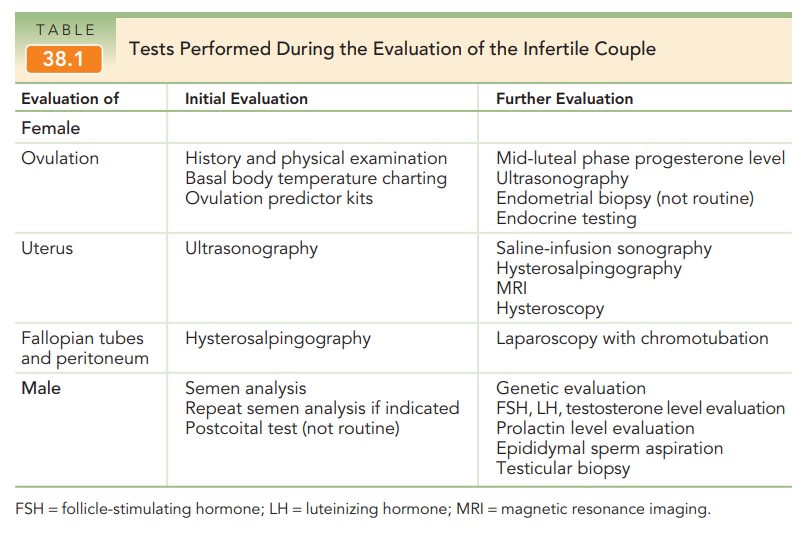

The most common causes of male and female infertility are investigated during the initial evaluation of infertility. It is important to recognize that more than one factor may be involved in a couple’s infertility (Table 38.1). As with any medical condition, a careful history and evaluation should reveal factors that may be involved in a couple’s infertility, such as medical disorders, medications, prior surgeries, pelvic infections or pelvic pain, sexual dysfunc-tion, and environmental and lifestyle factors (e.g., diet, exercise, tobacco use, drug use).

The timing of the initial evaluation depends primar-ily on the age of the female partner and a couple’s risk fac-tors for infertility. Because there is a decline in fecundity withadvancing maternal age, women over age 35 may benefit from a preliminary evaluation before 12 months of attempted conception. The initial assessment and treatment of infertility is com-monly provided by an obstetrician-gynecologist. More specialized evaluation and treatment may be performed by a reproductive endocrinologist.

Ovulation

A history of regular, predictable

menses strongly suggests ovulatory cycles. Furthermore, many women experience

characteristic symptoms associated with ovulation and the production of

progesterone: unilateral pelvic discomfort (mittelschmerz), fullness and

tenderness of the breasts, decreased vaginal secretions, abdominal bloating,

slight increase in body weight, and occasional episodes of depres-sion. These changes

rarely occur in anovulatory women. Therefore, a history of regular menses with

associated cyclic changes may be considered presumptive evidence of ovulation.

Secretion

of progesterone by the corpus luteum dominates the luteal phase of the menstrual

cycle, and persists if conception occurs.

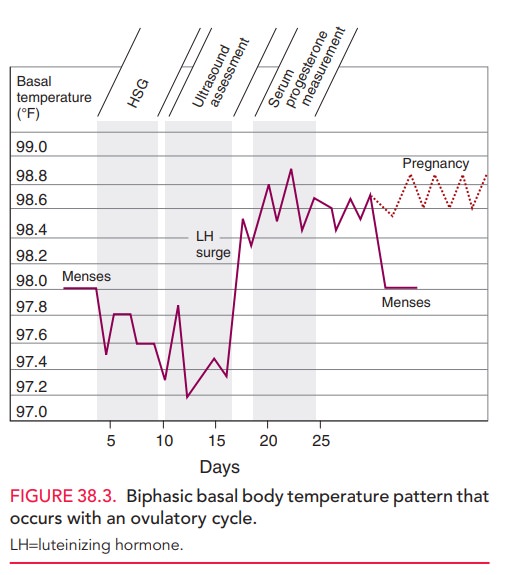

Progesterone acts on the endocervix to convert the thin, clear endocervical mucus into a sticky mucoid material. Progesterone also changes the brain’s thermoregulatory center setpoint, resulting in a basal body temperature rise of approximately 0.6°F. In the absence of pregnancy, invo-lution of the corpus luteum is associated with an abrupt decrease in progesterone production, normalization of the basal body temperature, and the commencement of menstruation.

Two tests provide indirect evidence of ovulation and can help predict the timing of ovulation. Basal body tempera-ture measurement reveals a characteristic biphasic tem-perature curve during most ovulatory cycles (Fig. 38.3). Special thermometers are available for this use. Upon awak-ening in the morning, the temperature must be obtained immediately before any physical activity.

The temperature drops at the time of menses, and

then rises 2 days after the peak of the luteinizing hormone (LH) surge,

coinciding with a rise in peripheral levels of progesterone. Oocyte release

occurs 1 day before the first temperature elevation, and the temperature

remains elevated for up to 14 days. This test for ovulation is readily

available, although cum-bersome to use; it can retrospectively identify

ovulation and the optimal time for intercourse, but can be difficult to

interpret. Urine LH kits are also

used to prospec-tively assess the presence and timing of ovulation based on

increased excretion of LH in the urine. Ovulation occurs approximately 24 hours

after urinary evidence of the LH surge. However, due to the pulsatile nature of

LH release, an LH surge can be missed if the test is only performed once daily.

Other diagnostic tests assess

ovulation using serumprogesterone levels

and the endometrial response toprogesterone.

A mid-luteal phase serum progesterone level can be used to retrospectively

assess ovulation. A value above 3 ng/mL implies ovulation; however, values

between 6 to 25 ng/mL may occur in a normal ovulatory cycle. Due to the

pulsatile nature of hormone secretion, a single low progesterone assessment

should be repeated. Another diagnostic procedure is the luteal phase endome-trial biopsy. The identification of secretory

endometriumconsistent with the day of the menstrual cycle confirms the presence

of progesterone; hence ovulation is implied. However, this procedure is

invasive, and histologic assess-ment of the endometrium does not reliably

differentiate infertile and fertile women. Therefore, the endometrial biopsy is

not routinely performed to assess ovulation or the endometrium.

If oligo-ovulation (sporadic and unpredictable ovula-tion) or anovulation (absence of ovulation) is

established, usually based on a menstrual cycle history of irregular cycles,

further testing is indicated to determine the underly-ing cause. A common cause

of ovulatory dysfunction in reproductive-age women is polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS); other causes include thyroid

disorders and hyper-prolactinemia. Women with PCOS often present with

oligomenorrhea and signs of hyperandrogenism such as hir-sutism, acne, and

weight gain. Furthermore, some infertile women present with amenorrhea, and this usually signifies anovu-lation.

Important causes of amenorrhea include pregnancy (a pregnancy test should

always be given), hypothalamic dysfunction (usually stress-related), ovarian

failure, or obstruction of the reproductive tract. Depending on the individual

case, laboratory testing for ovulatory dysfunction may include assessment of

serum levels of human chori-onic gonadotropin (hCG), thyroid-stimulating

hormone (TSH), prolactin, total testosterone, dehydroepiandros-terone sulfate

(DHEA-S), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), LH, and estradiol.

Treatment

of the etiology of ovulatory dysfunction may lead to resumption of ovulation

and improved fertility.

Anatomic Factors

The pelvic anatomy should be

assessed as a part of the infer-tility evaluation. Abnormalities of the uterus,

fallopian tubes, and peritoneum can all play a role in infertility.

UTERUS

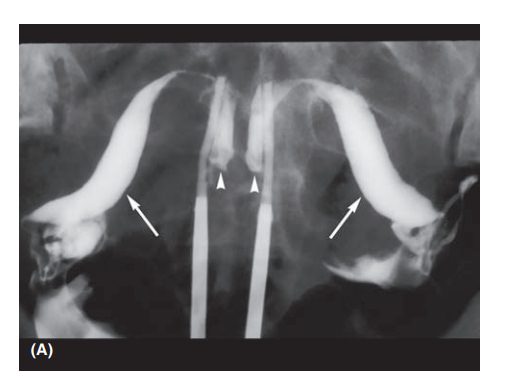

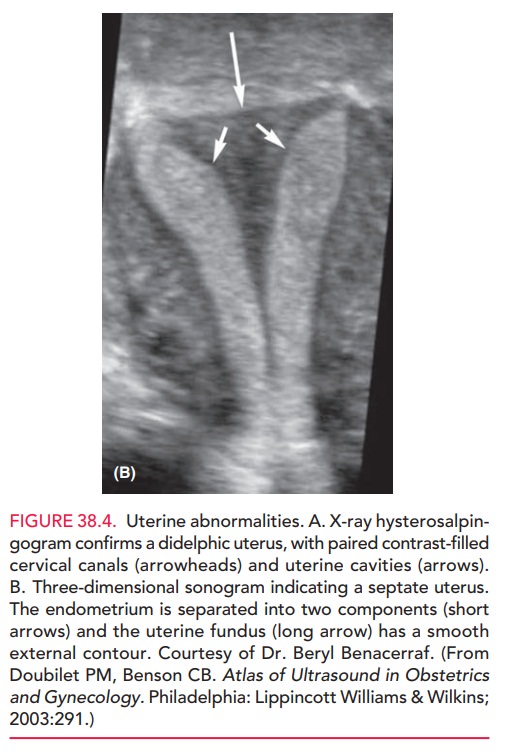

Uterine abnormalities are

commonly not sufficient to cause infertility; these disorders are usually

associated with preg-nancy loss. However,

assessment of the uterus is particularlyimportant if there is a history that

causes concern, such as abnor-mal bleeding, pregnancy loss, preterm delivery,

or previous uterine surgery. Potential uterine abnormalities include

leiomyomas,endometrial polyps, intrauterine adhesions, or congenital anomalies

(such as a septate, bicornuate, unicornuate, or didelphyic uterus) (Fig. 38.4).

Assessment of the uterus and endometrial cavity can be accomplished with

several imag-ing techniques; sometimes, a combination of modalities is

necessary to best assess pelvic anatomy (Box 38.1).

FALLOPIAN TUBES AND PERITONEUM

The

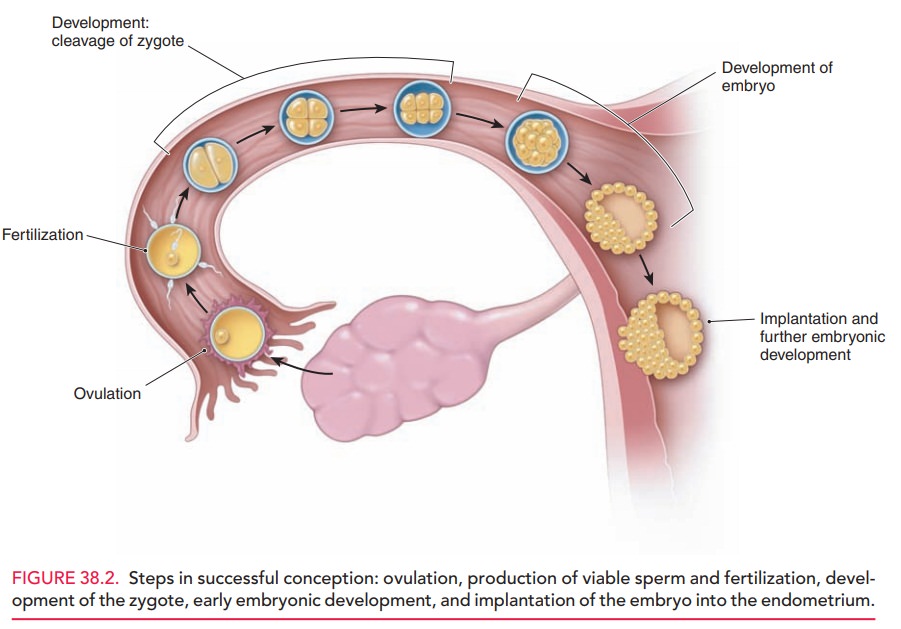

fallopian tubes are dynamic structures that are essential for ovum, sperm, and

embryo transport and fertilization.

At ovulation, the fimbriated end of the fallopian tube picks up the oocyte from the site of ovulation or from the pelvic cul-de-sac. The oocyte is transported to the ampullary portion of the fallopian tube where fertilization occurs (see Fig. 38.2). Subsequently, a zygote and then an embryo are formed. At 5 days following fertilization, the embryo enters the endometrial cavity, where implantation into the secretory endometrium occurs, followed by further embryo growth and development.

Box 38.1

Procedures Used in the Evaluation of Female Infertility

Transvaginal

ultrasonography: Used to visualize the vagina, cervix, uterus, and ovaries.

Saline-infusion

sonography: Assesses the myometrium, endometrium, and adnexa; sometimes used in

conjunction with magnetic resonance imaging.

Hysterosalpingography

(HSG): Provides information about the uterus and fallopian tubes’ structure and

function.

Hysteroscopy:

Used for evaluation and treatment of abnormalities identified by imaging

studies, such as removal of small leiomyomata, polyps, and adhesions

Laparoscopy: Used to visualize the pelvic organs as well as treat certain conditions, including endometriosis. Saline-infusion of the fallopian tubes can also be performed to test their patency.

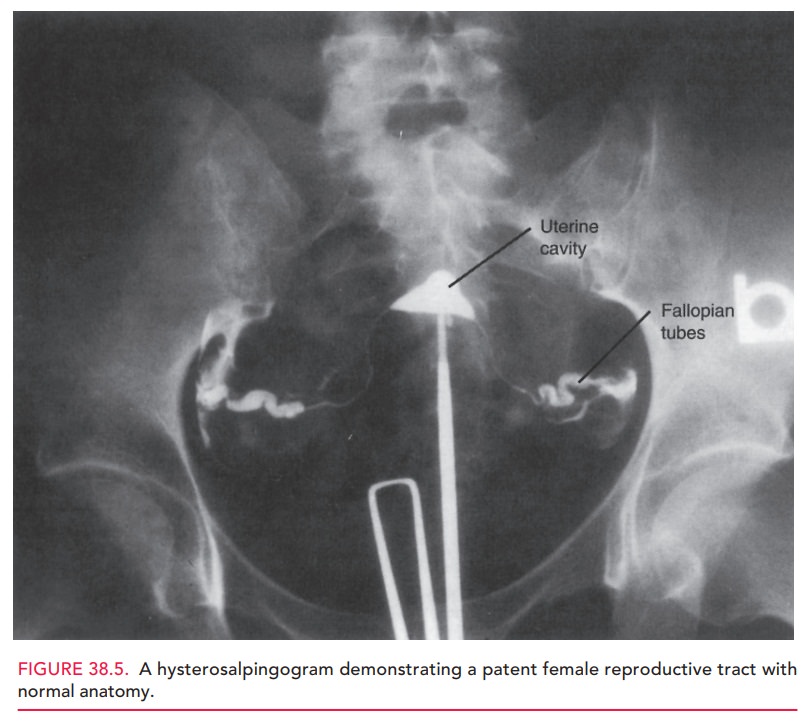

The fallopian tubes and pelvis can be evaluated with hysterosalpingography (HSG) or laparoscopy. There are several important

characteristics of a normal HSG (Fig. 38.5). The uterine cavity should be

smooth and sym-metrical; indentations or irregularities of the cavity suggest

the presence of leiomyomas, endometrial polyps, or intra-uterine adhesions. The

proximal two-thirds of the fallo-pian tube should be thin, approximating the

diameter of a pencil lead. The distal one-third comprises the ampulla, and

should appear dilated in comparison to the proximal portion of the tube. Free

spill of dye from the fimbria into the pelvis is appreciated as the cul-de-sac

and other struc-tures such as bowel are outlined by the accumulating dye. Failure

to observe dispersion of dye through a fallopian tube or throughout the pelvis

suggests the possibility of pelvic adhesions that restrict normal fallopian

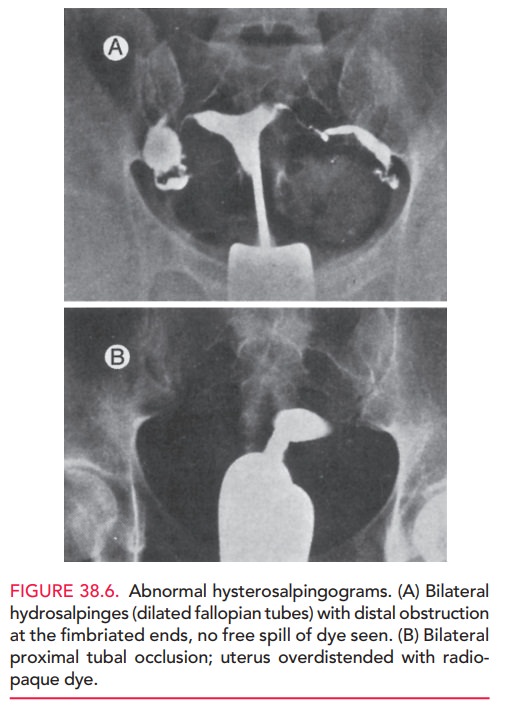

tube mobil-ity. Examples of abnormal hysterosalpingograms are shown in Figure

38.6.

Pelvic adhesions that affect the fallopian tubes or peri-toneum may occur because of pelvic infection (e.g., pelvic inflammatory disease, appendicitis), endometriosis, or abdominal or pelvic surgery. The sequelae of any of these processes or events can include fallopian tube scar-ring and obstruction. Pelvic infections are usually associated with sexually transmitted infections that cause acute sal-pingitis; commonly implicated organisms are Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhea. Endometriosis occurs with higher frequency in infertile women compared to fertile women, and can cause scarring and distortion of the fallopian tubes and other pelvic organs.

The HSG detects approximately 70%

of anatomic abnormalities of the genital tract. When there are abnormal-ities,

further diagnostic evaluation and treatment can be per-formed with hysteroscopy

and laparoscopy. Hysteroscopy evaluates the endometrium and the architecture of

the uter-ine cavity. Laparoscopy assesses pelvic structures including the

uterus, ovaries, and fallopian tubes as well as the pelvic peritoneum. During

laparoscopy, chromotubation should

be performed: similar to the HSG, a catheter is placed in the uterus and

colored dye is injected into the uterus while tubal patency and function is

directly assessed by laparoscopy. Laparoscopy also allows the diagnosis and

treatment of any pelvic abnormalities, such as adhesions and endometriosis.

Related Topics