Chapter: Psychiatric Mental Health Nursing : Somatoform Disorders

Etiology - Somatoform Disorders

ETIOLOGY

Psychosocial Theories

Psychosocial theorists believe that people with somatoform

disorders keep stress, anxiety, or frustration inside rather than expressing

them outwardly. This is called internalization. Clients express these

internalized feelings and stress through physical symptoms (somatization).

Both internalization and somatization are unconscious defense

mechanisms. Clients are not consciously aware of the process, and they do not

voluntarily control it.

People with somatoform disorders do not readily and directly

express their feelings and emotions verbally. They have tremendous difficulty

dealing with interpersonal conflict. When placed in situations involving

conflict or emotional stress, their physical symptoms appear to worsen. The

worsening of physical symptoms helps them to meet psychologic needs for

security, attention, and affection through primary and secondary gain

(Hollifield, 2005). Primary gains

are the direct external benefits that being sick provides, such as relief of

anxiety, conflict, or distress. Secondary

gains are the internal or personal ben-efits received from others because

one is sick, such as attention from family members and comfort measures (e.g.,

being brought tea, receiving a back rub). The person soon learns that he or she

“needs to be sick” to have their emotional needs met.

Somatization is associated most often with women, as evidenced by

the old term hysteria (Greek for

“wandering uterus”). Ancient theorists believed that unexplained female pains

resulted from migration of the uterus through-out the woman’s body.

Psychosocial theorists posit that increased incidence of somatization in women

may be related to various factors:

·

Boys in the United States are taught to be stoic and to “take it

like a man,” causing them to offer fewer physi-cal complaints as adults.

·

Women seek medical treatment more often than men, and it is more

socially acceptable for them to do so.

·

Childhood sexual abuse, which is related to somatiza-tion, happens

more frequently to girls.

·

Women more often receive treatment for psychiatric disorders with

strong somatic components such as depression.

Biologic Theories

Research has shown differences in the way that clients with

somatoform disorders regulate and interpret stimuli. These clients cannot sort

relevant from irrelevant stimuli and respond equally to both types. In other

words, they may experience a normal body sensation such as peristal-sis and

attach a pathologic rather than a normal meaning to it (Hollifield, 2005). Too

little inhibition of sensory input amplifies awareness of physical symptoms and

exag-gerates response to bodily sensations. For example, minor discomfort such

as muscle tightness becomes amplified because of the client’s concern and

attention to the tight-ness. This amplified sensory awareness causes the person

to experience somatic sensations as more intense, noxious, and disturbing

(Andreasen & Black, 2006).

Somatization disorder is found in 10% to 20% of female first-degree

relatives of people with this disorder. Conver-sion symptoms are found more

often in relatives of people with conversion disorder. First-degree relatives of

those with pain disorder are more likely to have depressive disor-ders, alcohol

dependence, and chronic pain (APA, 2000).

Cultural Considerations

The type and frequency of somatic symptoms and their meaning may

vary across cultures. Pseudoneurologic symptoms of somatization disorder in

Africa and South Asia include burning hands and feet and the nondelu-sional

sensation of worms in the head or ants under the skin. Symptoms related to male

reproduction are more common in some countries or cultures—for example, men in

India often have dhat, which is a

hypochondriacal concern about loss of semen. Somatization disorder is rare in

men in the United States but more common in Greece and Puerto Rico.

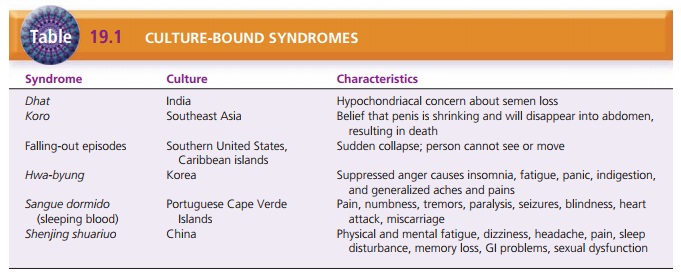

Many culture-bound syndromes have corresponding somatic symptoms

not explained by a medical condition (Table 19.1). Koro occurs in Southeast Asia and may be related to body dysmorphic

disorder. It is characterized by the belief that the penis is shrinking and

will disap-pear into the abdomen, causing the man to die. Falling-out episodes,

found in the southern United States and the Caribbean islands, are

characterized by a sudden collapse during which the person cannot see or move. Hwa-byung is a Korean folk syndrome

attributed to the suppression of anger and includes insomnia, fatigue, panic,

indiges-tion, and generalized aches and pains. Sangue dormido (sleeping blood) occurs among Portuguese Cape Verde

Islanders who report pain, numbness, tremors, paralysis, seizures, blindness,

heart attacks, and miscarriages. Shenjing

shuariuo occurs in China and includes physical and mental fatigue, dizziness, headache, pain, sleep dis-turbance,

memory loss, gastrointestinal problems, and sexual dysfunction (Mojtabai,

2005).

Treatment

Treatment focuses on managing symptoms and improving quality of

life. The health care provider must show empathy and sensitivity to the

client’s physical complaints. A trusting relationship helps to ensure that clients

stay with and receive care from one provider instead of “doctor shopping.”

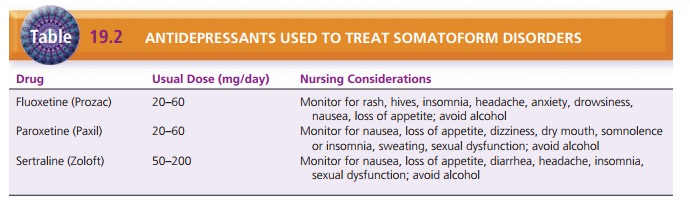

For many clients, depression may accompany or result from

somatoform disorders (Ferrari, Galeazzi, Mackinnon, Rigatelli, 2008). Thus,

antidepressants help in some cases. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

such as fluoxetine (Prozac), sertraline (Zoloft), and paroxetine (Paxil) are

used most commonly (Table 19.2).

For clients with pain disorder, referral to a chronic pain clinic

may be useful. Clients learn methods of pain management such as visual imaging

and relaxation. Ser-vices such as physical therapy to maintain and build

mus-cle tone help to improve functional abilities. Providers should avoid

prescribing and administering narcotic anal-gesics to these clients because of

the risk for dependence or abuse. Clients can use nonsteroidal

anti-inflammatory agents to help reduce pain.

Involvement in therapy groups is beneficial for some people with

somatoform disorders. Studies of clients with somatization disorder who participated

in a structured cognitive-behavioral group showed evidence of improved physical

and emotional health 1 year later (Hollifield, 2005). The overall goals of the

group were offering peer support, sharing methods of coping, and perceiving and

expressing emotions. Abramowitz and Braddock (2006) found that clients with

hypochondriasis who were willing to participate in cognitive-behavioral therapy

and take medications were able to alter their erroneous perceptions of threat

(of illness) and improve. Cognitive-behavioral therapy also produced

significant improvement in clients with somatization disorder (Allen, Woolfolk,

Escobar, Gara, & Hamer, 2006).

Related Topics