Chapter: Psychiatric Mental Health Nursing : Therapeutic Relationships

Establishing the Therapeutic Relationship

ESTABLISHING THE THERAPEUTIC

RELATIONSHIP

The nurse who has self-confidence rooted in self- awareness is ready

to establish appropriate therapeutic relationships with clients. Because

personal growth is ongoing over one’s lifetime, the nurse cannot expect to have

complete self-knowledge. Awareness of his or her strengths and limita-tions at

any particular moment, however, is a good start.

Phases

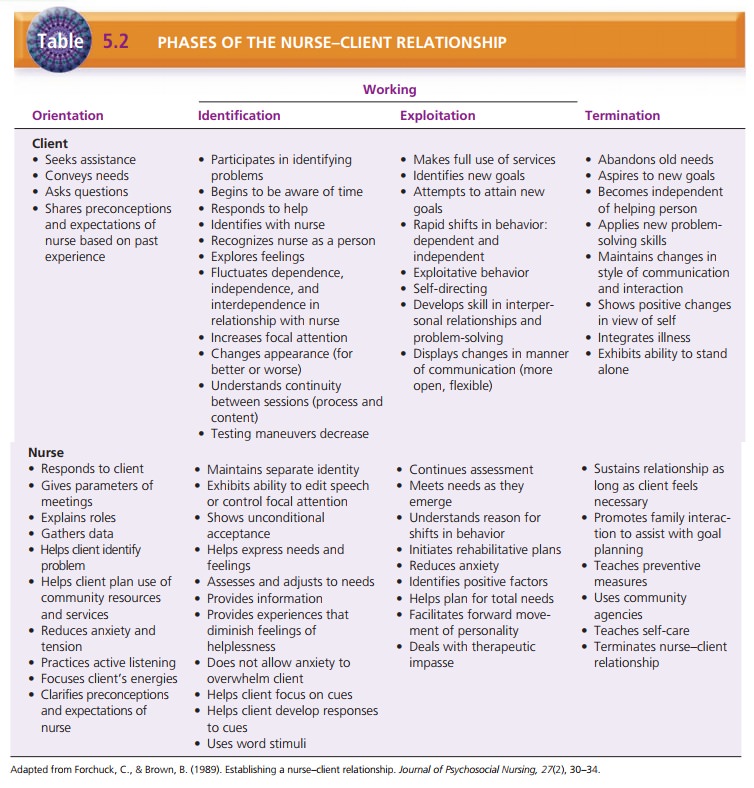

Peplau studied and wrote about the interpersonal pro-cesses and the

phases of the nurse–client relationship for 35 years. Her work provides the

nursing profession with a model that can be used to understand and document

prog-ress with interpersonal interactions. Peplau’s model (1952) has three

phases: orientation, working, and resolution or termination (Table 5.2). In

real life, these phases are not that clear-cut; they overlap and interlock.

Orientation

The orientation phase

begins when the nurse and client meet and ends when the client begins to

identify problems to examine. During the orientation phase, the nurse

estab-lishes roles, the purpose of meeting, and the parameters of subsequent

meetings; identifies the client’s problems; and clarifies expectations.

Before meeting the client, the nurse has important work to do. The

nurse reads background materials available on the client, becomes familiar with

any medications the cli-ent is taking, gathers necessary paperwork, and

arranges for a quiet, private, and comfortable setting. This is the time for

self-assessment. The nurse should consider his or her personal strengths and

limitations in working with this client. Are there any areas that might signal

difficulty because of past experiences? For example, if this client is a spouse

batterer and the nurse’s father was also one, the nurse needs to consider the

situation: How does it make him or her feel? What memories does it prompt, and

can he or she work with the client without these memories interfering? The

nurse must examine preconceptions about the client and ensure that he or she

can put them aside and get to know the real person. The nurse must come to each

client without preconceptions or prejudices. It may be useful for the nurse to

discuss all potential prob-lem areas with the instructor.

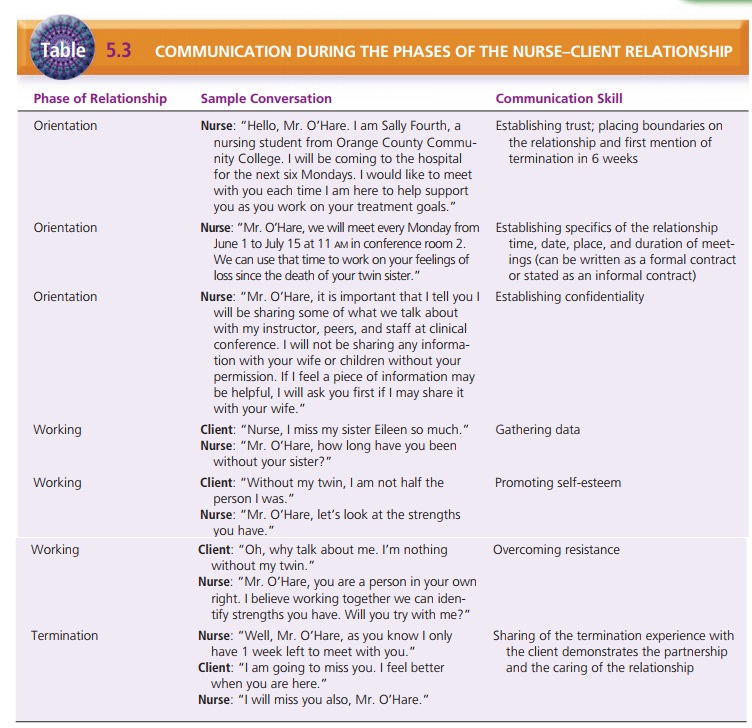

During the orientation phase, the nurse begins to build trust with

the client. It is the nurse’s responsibility to establish a therapeutic

environment that fosters trust and understanding (Table 5.3). The nurse should

share appropriate information about himself or herself at this time, including

name, reason for being on the unit, and level of schooling: For example,

“Hello, James. My name is Miss Ames and I will be your nurse for the next six

Tuesdays. I am a senior nursing student at the University of Mississippi.”

The nurse needs to listen closely to the client’s history,

perceptions, and misconceptions. He or she needs to con-vey empathy and

understanding. If the relationship gets off to a positive start, it is more

likely to succeed and to meet established goals.

At the first meeting, the client may be distrustful if pre-vious

relationships with nurses have been unsatisfactory. The client may use rambling

speech, act out, or exaggerate episodes as ploys to avoid discussing the real

problems. It may take several sessions until the client believes that he or she

can trust the nurse.

Nurse–Client Contracts. Although many clients have

had prior experiences in the mental health system,

the nurse

must once again outline the responsibilities of the nurse and the

client. At the outset, both nurse and client should agree on these

responsibilities in an informal or verbal contract. In some instances, a formal

or written contract may be appropriate; examples include if a written contract

has been necessary in the past with the client or if the cli-ent “forgets” the

agreed-on verbal contract.

The contract should state the following:

·

Time, place, and length of sessions

·

When sessions will terminate

·

Who will be involved in the treatment plan (family members or

health team members)

·

Client responsibilities (arrive on time and end on time)

·

Nurse’s responsibilities (arrive on time, end on time, maintain

confidentiality at all times, evaluate progress with client, and document

sessions).

Confidentiality. Confidentiality means respecting the client’s right to keep

private any information about his or her mental and physical health and related

care. It means allowing only those dealing with the client’s care to have

access to the information that the client divulges. Only under precisely

defined conditions can third parties have access to this information; for

example, in many states the law requires that staff report suspected child and

elder abuse.

Adult clients can decide which family members, if any, may be

involved in treatment and may have access to clinical information. Ideally, the

people close to the client and responsible for his or her care are involved.

The cli-ent must decide, however, who will be included. For the client to feel

safe, boundaries must be clear. The nurse must clearly state information about

who will have access to client assessment data and progress evaluations. He or

she should tell the client that members of the mental health team share

appropriate information among them-selves to provide consistent care and that

only with the client’s permission will they include a family member. If the

client has an appointed guardian, that person can review client information and

make treatment decisions that are in the client’s best interest. For a child,

the parent or appointed guardian is allowed access to information and can make

treatment decisions as outlined by the health-care team.

The nurse must be alert if a client asks him or her to keep a

secret because this information may relate to the client’s harming himself or

herself or others. The nurse must avoid any promises to keep secrets. If the

nurse has promised not to tell before hearing the message, he or she could be

jeopardizing the client’s trust. In most cases, even when the nurse refuses to

agree to keep information secret, the client continues to relate issues anyway.

The following is an example of a good response to a client who is suicidal but

requests secrecy:

Client: “I am going to jump off the 14th floor of my apartment building tonight, but please don’t tell

anyone.”

Nurse: “I cannot keep such a promise, espe-cially if it involves your

safety. I sense you arefeeling frightened. The staff and I will help you stay

safe.”

The Tarasoff vs. Regents of

the University of California (1976) decision releases professionals from

privileged communication with their clients should a client make a homicidal

threat. The decision requires the nurse to notify intended victims and police

of such a threat. In this cir-cumstance, the nurse must report the homicidal

threat tothe nursing supervisor and attending physician so that both the police

and the intended victim can be notified. This is called a duty to warn.

The nurse documents the client’s problems with planned

interventions. The client must understand that the nurse will collect data about

him or her that helps in making a diagnosis, planning health care (including

medications), and protecting the client’s civil rights. The client needs to

know the limits of confidentiality in nurse–client interac-tions and how the

nurse will use and share this informa-tion with professionals involved in

client care.

Self-Disclosure. Self-disclosure means revealing per-sonal information such as

biographical information and personal ideas, thoughts, and feelings about

oneself to cli-ents. Traditionally, conventional wisdom held that nurses should

share only their name and give a general idea about their residence, such as “I

live in Ocean County.” Now, however, it is believed that some purposeful,

well-planned, self-disclosure can improve rapport between the nurse and the

client. The nurse can use self-disclosure to convey support, educate clients,

and demonstrate that a client’s anxiety is normal and that many people deal

with stress and problems in their lives.

Self-disclosure may help the client feel more comfort-able and more

willing to share thoughts and feelings, or help the client gain insight into

his or her situation. When using self-disclosure, the nurse must also consider

cultural factors. Some clients may deem self-disclosure inappropriate or too personal,

causing the client discom-fort. Disclosing personal information to a client can

be harmful and inappropriate, so it must be planned and considered thoughtfully

in advance. Spontaneously self-disclosing personal information can have

negative results. For example, when working with a client whose parents are

getting a divorce, the nurse says, “My parents got a divorce when I was 12 and

it was a horrible time for me.” The nurse has shifted the focus away from the

client and has given the client the idea that this experience will be horrible

for the client. Although the nurse may have meant to communicate empathy, the

result can be quite the opposite.

Working

The working phase of the

nurse–client relationship is usually divided into two subphases: During problem identification, the client identifies the issues or concerns causing problems. During exploitation, the nurse guides the

client to examine feelings and responses and to develop better coping skills

and a more positive self-image; this encourages behavior change and develops

independence. (Note that Peplau’s use of the word exploi-tation had a very different meaning than current usage, which involves unfairly using or taking

advantage of a person or situation. For that reason, this phase is better![]()

![]() conceptualized as intense exploration and

elaboration on earlier themes that the client discussed.) The trust

estab-lished between nurse and client at this point allows them to examine the

problems and to work on them within the security of the relationship. The

client must believe that the nurse will not turn away or be upset when the

client reveals experiences, issues, behaviors, and problems. Sometimes the

client will use outrageous stories or act-ing-out behaviors to test the nurse.

Testing behavior chal-lenges the nurse to stay focused and not to react or to

be distracted. Often when the client becomes uncomfortable because he or she is

getting too close to the truth, he or she will use testing behaviors to avoid

the subject. The nurse may respond by saying, “It seems as if we have hit an

uncomfortable spot for you. Would you like to let it go for now?” This

statement focuses on the issue at hand and diverts attention from the testing

behavior.

conceptualized as intense exploration and

elaboration on earlier themes that the client discussed.) The trust

estab-lished between nurse and client at this point allows them to examine the

problems and to work on them within the security of the relationship. The

client must believe that the nurse will not turn away or be upset when the

client reveals experiences, issues, behaviors, and problems. Sometimes the

client will use outrageous stories or act-ing-out behaviors to test the nurse.

Testing behavior chal-lenges the nurse to stay focused and not to react or to

be distracted. Often when the client becomes uncomfortable because he or she is

getting too close to the truth, he or she will use testing behaviors to avoid

the subject. The nurse may respond by saying, “It seems as if we have hit an

uncomfortable spot for you. Would you like to let it go for now?” This

statement focuses on the issue at hand and diverts attention from the testing

behavior.

The nurse must remember that it is the client who examines and

explores problem situations and relation-ships. The nurse must be nonjudgmental

and refrain from giving advice; the nurse should allow the client to analyze

situations. The nurse can guide the client to observe pat-terns of behavior and

whether or not the expected response occurs. For example, a client who suffers

from depression complains to the nurse about the lack of concern her chil-dren

show her. With the assistance and guidance of the nurse, the client can explore

how she communicates with her children and may discover that her communication

involves complaining and criticizing. The nurse can then help the client

explore more effective ways of communi-cating in the future. The specific tasks

of the working phase include the following:

·

Maintaining the relationship

·

Gathering more data

·

Exploring perceptions of reality

·

Developing positive coping mechanisms

·

Promoting a positive self-concept

·

Encouraging verbalization of feelings

·

Facilitating behavior change

·

Working through resistance

·

Evaluating progress and redefining goals as appropriate

·

Providing opportunities for the client to practice new behaviors

·

Promoting independence.

As the nurse and client work together, it is common for the client

unconsciously to transfer to the nurse feelings he or she has for significant

others. This is called transfer-ence.

For example, if the client has had negative experi-ences with authority

figures, such as a parent or teachers or principals, he or she may display

similar reactions of negativity and resistance to the nurse, who also is viewed

as an authority. A similar process can occur when the nurse responds to the

client based on personal unconscious needs and conflicts; this is called countertransference. For example, if

the nurse is the youngest in her family and often felt as if no one listened to

her when she was a child, she may respond with anger to a client who does not

listen or resists her help. Again, self-awareness is important so that the

nurse can identify when transference and counter-transference might occur. By

being aware of such “hot spots,” the nurse has a better chance of responding

appro-priately rather than letting old unresolved conflicts inter-fere with the

relationship.

Termination

The termination or

resolution phase is the final stage in the nurse–client relationship. It

begins when the prob-lems are resolved, and it ends when the relationship is

ended. Both nurse and client usually have feelings about ending the

relationship; the client especially may feel the termination as an impending

loss. Often clients try to avoid termination by acting angry or as if the

problem has not been resolved. The nurse can acknowledge the client’s angry

feelings and assure the client that this response is normal to ending a

relationship. If the client tries to reopen and discuss old resolved issues,

the nurse must avoid feeling as if the sessions were unsuccessful; instead, he

or she should identify the client’s stalling maneuvers and refocus the client

on newly learned behaviors and skills to handle the problem. It is appropriate

to tell the client that the nurse enjoyed the time spent with the cli-ent and

will remember him or her, but it is inappropriate for the nurse to agree to see

the client outside the thera-peutic relationship.

Related Topics