Chapter: Psychiatric Mental Health Nursing : Therapeutic Relationships

Components of a Therapeutic Relationship

COMPONENTS OF A THERAPEUTIC RELATIONSHIP

Many factors can enhance the nurse–client relationship, and it is the nurse’s responsibility to develop them. These factors promote communication and enhance relation-ships in all aspects of the nurse’s life.

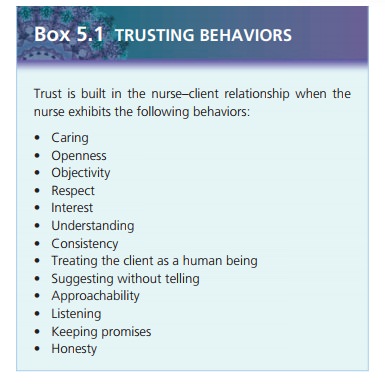

Trust

The nurse–client relationship requires trust. Trust builds when the client is confident in the nurse and when the nurse’s presence conveys integrity and reliability. Trust develops when the client believes that the nurse will be consistent in his or her words and actions and can be relied on to do what he or she says. Some behaviors the nurse can exhibit to help build the client’s trust include caring, interest, understanding, consistency, honesty, keeping promises, and listening to the client. A caring therapeutic nurse–client relationship enables trust to develop so that the client can accept the assistance being offered (Warelow, Edward, & Vinek, 2008).

Congruence occurs when words and actions match. For example, the nurse says to the client, “I have to leave now to go to a clinical conference, but I will be back at 2 PM,” and indeed returns at 2 PM to see the client. The nurse needs to exhibit congruent behaviors to build trust with the client.

Trust erodes when a client sees inconsistency between what the nurse says and does. Inconsistent or incongru-ent behaviors include making verbal commitments and not following through on them. For example, the nurse tells the client she will work with him every Tuesday at 10 AM, but the very next week she has a conflict with her conference schedule and does not show up. Another example of incongruent behavior is when the nurse’s voice or body language is inconsistent with the words he or she speaks. For example, an angry client confronts a nurse and accuses her of not liking her. The nurse responds by saying, “Of course I like you, Nancy! I am here to help you.” But as she says these words, the nursebacks away from Nancy and looks over her shoulder: the verbal and nonverbal components of the message do not match.

When working with a client with psychiatric problems, some of the symptoms of the disorder, such as paranoia, low self-esteem, and anxiety, may make trust difficult to establish. For example, a client with depression has little psychic energy to listen to or comprehend what the nurse is saying. Likewise, a client with panic disorder may be too anxious to focus on the nurse’s communication. Although clients with mental disorders frequently give incongruent messages because of their illness, the nurse must continue to provide consistent congruent messages. Examining one’s own behavior and doing one’s best to make messages clear, simple, and congruent help to facilitate trust between the nurse and the client.

Genuine Interest

When the nurse is comfortable with himself or herself, aware of his or her strengths and limitations, and clearly focused, the client perceives a genuine person showing genuine interest. A client with mental illness can detect when someone is exhibiting dishonest or artificial behav-ior such as asking a question and then not waiting for the answer, talking over him or her, or assuring him or her everything will be all right. The nurse should be open and honest and display congruent behavior. Some-times, however, responding with truth and honesty alone does not provide the best professional response. In such cases, the nurse may choose to disclose to the client a personal experience related to the client’s current con-cerns. It is essential, however, that the nurse is very selective about personal examples. These examples should be from the nurse’s past experience, not a current problem the nurse is still trying to resolve, or a recent, still painful experience. Self-disclosure examples are most helpful to the client when they represent common day-to-day experiences and do not involve value-laden topics. For example, the nurse might share an experi-ence of being frustrated with a coworker’s tardiness or being worried when a child failed an exam at school. It is rarely helpful to share personal experiences such as going through a divorce or the infidelity of a spouse or partner. Self-disclosure can be helpful on occasion, but the nurse must not shift emphasis to his or her own problems rather than the client’s.

Empathy

Empathy is the ability of the nurse to perceive the mean-ings and feelings of the client and to communicate that understanding to the client. It is considered one of the essential skills a nurse must develop. Being able to put himself or herself in the client’s shoes does not mean that the nurse has had the exact experiences as the client. Nevertheless, by listening and sensing the importance of the situation to the client, the nurse can imagine the cli-ent’s feelings about the experience. Both the client and the nurse give a “gift of self” when empathy occurs—the client by feeling safe enough to share feelings and the nurse by listening closely enough to understand. Empa-thy has been shown to positively influence client outcomes. Clients tend to feel better about themselves and more understood when the nurse is empathetic (Welch, 2005).

From these empathetic moments, a bond can be estab-lished to serve as the foundation for the nurse–client rela-tionship.

The nurse must understand the difference between empathy and sympathy (feelings of concern or compassion one shows for another). By expressing sympathy, the nurse may project his or her personal concerns onto the client, thus inhibiting the client’s expression of feelings. In the above example, the nurse using sympathy would have responded, “I know how confusing sons can be. My son confuses me, too, and I know how bad that makes you feel.” The nurse’s feelings of sadness or even pity could influence the relationship and hinder the nurse’s abilities to focus on the client’s needs. Sympathy often shifts the emphasis to the nurse’s feelings, hindering the nurse’s ability to view the client’s needs objectively.

![]()

![]()

Acceptance

The nurse who does not become upset or respond nega-tively to a client’s outbursts, anger, or acting out conveys acceptance to the client. Avoiding judgments of the per-son, no matter what the behavior, is acceptance. This does not mean acceptance of inappropriate behavior but acceptance of the person as worthy. The nurse must set boundaries for behavior in the nurse–client relationship. By being clear and firm without anger or judgment, the nurse allows the client to feel intact while still conveying that certain behavior is unacceptable. For example, a cli-ent puts his arm around the nurse’s waist. An appropri-ate response would be for the nurse to remove his hand and say,

“John, do not place your hand on me. We are working on your relationship with your girl-friend and that does not require you to touch me. Now, let’s continue.”

An inappropriate response would be,

“John, stop that! What’s gotten into you? I am leaving, and maybe I’ll return tomorrow.”

Leaving and threatening not to return punish the client while failing to clearly address the inappropriate behavior.

Positive Regard

The nurse who appreciates the client as a unique worth while human being can respect the client regardless of his or her behavior, background, or lifestyle. This uncontional nonjudgmental attitude is known as positive regard and implies respect. Calling the client by name, spending time with the client, and listening and responding openly are measures by which the nurse conveys respect and positive regard to the client. The nurse also conveys positive regard by considering the client’s ideas and preferences when planning care. Doing so shows that the nurse believes the client has the ability to make positive and meaningful contributions to his or her own plan of care. The nurse relies on presence, or attending, which is using nonverbal and verbal communication techniques to make the client aware that he or she is receiving full attention. Nonverbal techniques that create an atmosphere of presence include leaning toward the client, maintaining eye contact, being relaxed, having arms resting at the sides, and having an interested but neutral attitude. Verbally attending means that the nurse avoids communicating value judgments about the client’s behavior. For example, the client maysay, “I was so mad, I yelled and screamed at my mother for an hour.” If the nurse responds with, “Well, that didn’thelp, did it?” or “I can’t believe you did that,” the nurse iscommunicating a value judgment that the client was“wrong” or “bad.” A better response would be “What hap-pened then?” or “You must have been really upset.” The nurse maintains attention on the client and avoids com-municating negative opinions or value judgments about the client’s behavior.

Self-Awareness and Therapeutic Use of Self

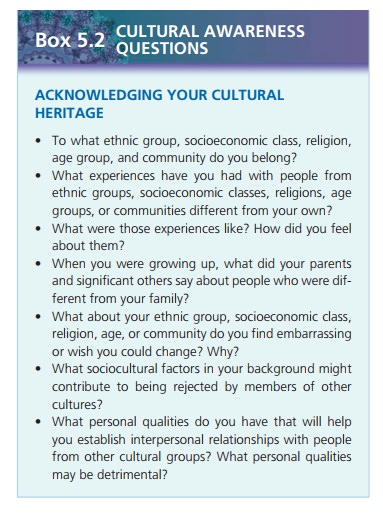

Before he or she can begin to understand clients, the nurse must first know himself or herself. Self-awareness is the process of developing an understanding of one’s own val-ues, beliefs, thoughts, feelings, attitudes, motivations, prejudices, strengths, and limitations and how these quali-ties affect others. It allows the nurse to observe, pay atten-tion to, and understand the subtle responses and reactions of clients when interacting with them.

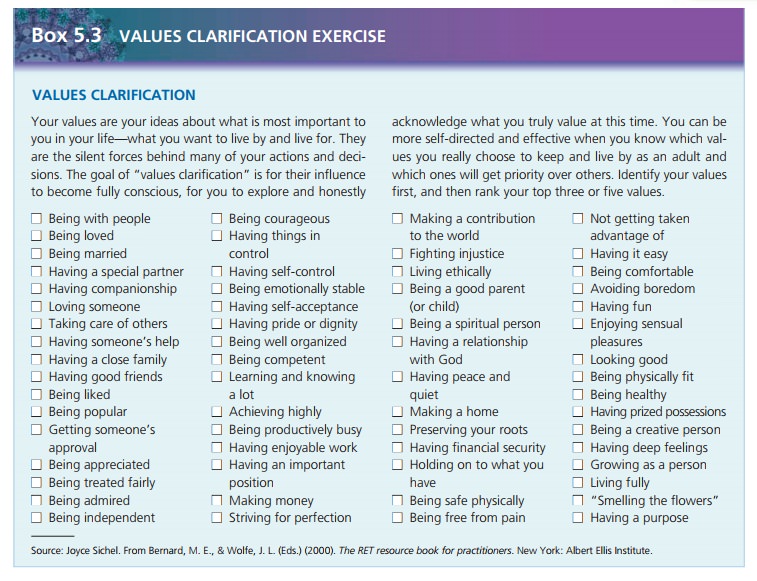

Values are abstract standards that give a person a sense of right and wrong and establish a code of conduct for liv-ing. Sample values include hard work, honesty, sincerity, cleanliness, and orderliness. To gain insight into oneself and personal values, the values clarification process is helpful.

The values clarification process has three steps: choos-ing, prizing, and acting. Choosing is when the person con-siders a range of possibilities and freely chooses the valuethat feels right. Prizing is when the person considers the value, cherishes it, and publicly attaches it to himself or herself. Acting is when the person puts the value into action. For example, a clean and orderly student has been assigned to live with another student who leaves clothes and food all over their room. At first the orderly student is unsure why she hesitates to return to the room and feels tense around her roommate. As she examines the situa-tion, she realizes that they view the use of personal space differently (choosing). Next she discusses her conflict and choices with her adviser and friends (prizing). Finally, she decides to negotiate with her roommate for a compromise (acting).

Beliefs are ideas that one holds to be true, for exam-ple, “All old people are hard of hearing,” “If the sun is shining, it will be a good day,” or “Peas should be planted on St. Patrick’s Day.” Some beliefs have objective evidence to substantiate them. For example, people who believe in evolution have accepted the evidence that supports this explanation for the origins of life. Other beliefs are irra-tional and may persist, despite these beliefs having no supportive evidence or the existence of contradictory empirical evidence. For example, many people harbor irrational beliefs about cultures different from their own that they developed simply from others’ comments or fear of the unknown, not from any evidence to support such beliefs.

Attitudes are general feelings or a frame of reference around which a person organizes knowledge about the world. Attitudes, such as hopeful, optimistic, pessimistic, positive, and negative, color how we look at the world and people. A positive mental attitude occurs when a person chooses to put a positive spin on an experience, a comment, or a judgment. For example, in a crowded gro-cery line, the person at the front pays with change, slowly counting it out. The person waiting in line who has a positive attitude would be thankful for the extra minutes and would begin to use them to do deep-breathing exer-cises and to relax. A negative attitude also colors how one views the world and other people. For example, a person who has had an unpleasant experience with a rude waiter may develop a negative attitude toward all waiters. Such a negative attitude might cause the person to behave impolitely and unpleasantly with every waiter he or she encounters.

The nurse should reevaluate and readjust beliefs and attitudes periodically as he or she gains experience and wisdom. Ongoing self-awareness allows the nurse to accept values, attitudes, and beliefs of others that may differ from his or her own. A person who does not assess personal attitudes and beliefs may hold a prejudice or bias toward a group of people because of preconceived ideas or stereotypical images of that group. It is not uncom-mon for a person to be ethnocentric about his or her own culture (believing one’s own culture to be superior to others), particularly when the person has no experience with any culture than his or her own.

Therapeutic Use of Self

By developing self-awareness and beginning to understand his or her attitudes, the nurse can begin to use aspects of his or her personality, experiences, values, feelings, intel-ligence, needs, coping skills, and perceptions to establish relationships with clients. This is called therapeutic use of self. Nurses use themselves as a therapeutic tool to estab-lish therapeutic relationships with clients and to help cli-ents grow, change, and heal. Peplau (1952), who described this therapeutic use of self in the nurse–client relationship, believed that nurses must clearly understand themselves to promote their clients’ growth and to avoid limiting cli-ents’ choices to those that nurses value.

The nurse’s personal actions arise from conscious and unconscious responses that are formed by life experiences and educational, spiritual, and cultural values. Nurses (and all people) tend to use many automatic responses or behaviors just because they are familiar. They need to examine such accepted ways of responding or behaving and evaluate how they help or hinder the therapeutic relationship.

One tool that is useful in learning more about oneself is the Johari window (Luft, 1970), which creates a “word portrait” of a person in four areas and indicates how well that person knows himself or herself and communicates with others. The four areas evaluated are as follows:

· Quadrant 1: Open/public self—qualities one knows about oneself and others also know.

· Quadrant 2: Blind/unaware self—qualities known only to others.

· Quadrant 3: Hidden/private self—qualities known only to oneself.

· Quadrant 4: Unknown—an empty quadrant to symbol-ize qualities as yet undiscovered by oneself or others.

In creating a Johari window, the first step is for the nurse to appraise his or her own qualities by creating a list of them: values, attitudes, feelings, strengths, behaviors, accomplishments, needs, desires, and thoughts. The sec-ond step is to find out others’ perceptions by interviewing them and asking them to identify qualities, both positive and negative, they see in the nurse. To learn from this exercise, the opinions given must be honest; there must be no sanctions taken against those who list negative quali-ties. The third step is to compare lists and assign qualities to the appropriate quadrant.

If quadrant 1 is the longest list, this indicates that the nurse is open to others; a smaller quadrant 1 means that the nurse shares little about himself or herself with others. If quadrants 1 and 3 are both small, the person demon-strates little insight. Any change in one quadrant is reflected by changes in other quadrants. The goal is to work toward moving qualities from quadrants 2, 3, and 4 into quadrant 1 (qualities known to self and others). Doing so indicates that the nurse is gaining self-knowledge and awareness. See the accompanying figure for an example of a Johari window.

Patterns of Knowing

Nurse theorist Hildegard Peplau (1952) identified pre-conceptions, or ways one person expects another to behave or speak, as a roadblock to the formation of anauthentic relationship. Preconceptions often prevent peo-ple from getting to know one another. Preconceptions and different or conflicting personal beliefs and values may prevent the nurse from developing a therapeutic relation-ship with a client. Here is an example of preconceptions that interfere with a therapeutic relationship: Mr. Lopez, a client, has the preconceived stereotypical idea that all male nurses are homosexual and refuses to have Samuel, a male nurse, take care of him. Samuel has a preconceived stereotypical notion that all Hispanic men use switch-blades, so he is relieved that Mr. Lopez has refused to work with him. Both men are missing the opportunity to do some important work together because of incorrect preconceptions.

![]()

![]()

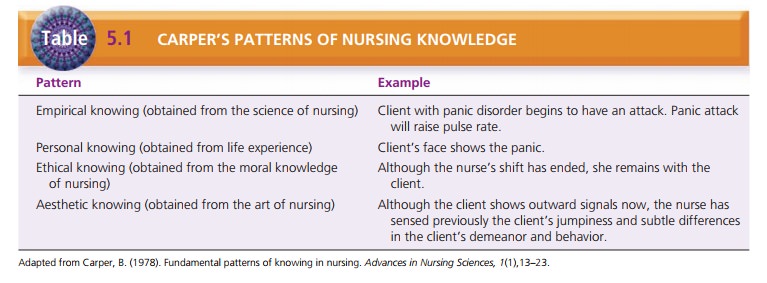

Carper (1978) identified four patterns of knowing in nursing: empirical knowing (derived from the science of nursing), personal knowing (derived from life experi-ences), ethical knowing (derived from moral knowledge of nursing), and aesthetic knowing (derived from the art of nursing). These patterns provide the nurse with a clear method of observing and understanding every client inter-action. Understanding where knowledge comes from and how it affects behavior helps the nurse become more self-aware (Table 5.1). Munhall (1993) added another pattern that she called unknowing: For the nurse to admit she or he does not know the client or the client’s subjective world opens the way for a truly authentic encounter. The nurse in a state of unknowing is open to seeing and hearing the client’s views without imposing any of his or her values or viewpoints. In psychiatric nursing, negative preconcep-tions on the nurse’s part can adversely affect the therapeu-tic relationship; thus, it is especially important for the nurse to work on developing this openness and acceptance toward the client.

Related Topics