Chapter: Professional Ethics in Engineering : Global Issues

Environmental Ethics Through Engineering Ecology and Economics

ENVIRONMENTAL ETHICS THROUGH ENGINEERING

ECOLOGY AND ECONOMICS:

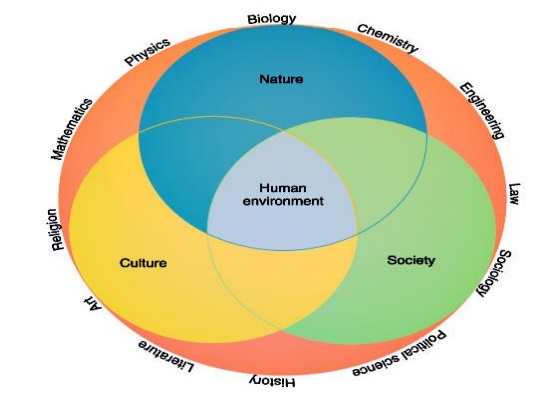

In addition to global warming, environmental

challenges confront us at every turn, including myriad forms of pollution,

human-population growth, extinction of species, destruction of ecosystems,

depletion of natural resources, and nuclear waste. Today there is a wide

consensus that we need concerted environmental responses that combine economic

realism with ecological awareness. For their part, many engineers are now

showing leadership in advancing ecological awareness. In this chapter, we

discuss some ways in which this responsibility for the environment is shared by

engineers, industry, government, and the public. We also introduce some

perspectives developed in the new field of environmental ethics that enter into

engineers‘ personal commitments and ideals.

Engineering ecology and economics:

Two powerful metaphors have dominated thinking

about the environment: the invisible hand and the tragedy of the commons. Both

metaphors are used to highlight unintentional impacts of the marketplace on the

environment, but one is optimistic and the other is cautionary about those

impacts. Each contains a large part of the truth, and they need to be

reconciled and balanced. The first metaphor was set forth by Adam Smith in 1776

in The Wealth of Nations, the founding text of modern economics. Smith conceived

of an invisible (and divine) hand governing the Market place in a seemingly

paradoxical manner. According to Smith, businesspersons think only of their own

self-interest: ―It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or

the baker, that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own

interest. Yet, although ―he intends only his own gain,‖ he is ―led by an

invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention. By

pursuing his own interest he frequently promotes that of the society more

effectually than when he really intends to promote it. I have never known much

good done by those who affected to trade for the public good.

In fact, professionals and many businesspersons

do profess to ―trade for the public good,‖ claiming a commitment to hold

paramount the safety, health, and welfare of the public. Although they are

predominantly motivated by self-interest, they also have genuine moral concern

for others.3 Nevertheless, Smith‘s metaphor of the invisible hand contains a

large element of truth. By pursuing self-interest, the businessperson, as

entrepreneur, creates new companies that provide goods and services for

consumers. Moreover, competition pressures corporations to continually improve

the quality of their products and to lower prices, again benefiting consumers.

In addition, new jobs are created for employees and suppliers, and the wealth

generated benefits the wider community through consumerism, taxes, and

philanthropy.

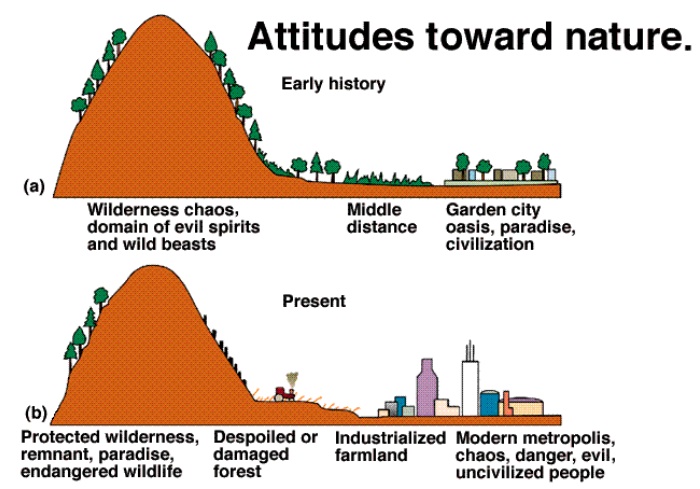

Despite its large element of truth, the

invisible hand metaphor does not adequately take account of damage to the

environment. Writing in the eighteenth century, with its seemingly infinite

natural resources, Adam Smith could not have foreseen the cumulative impact of

expanding populations, unregulated capitalism, and market ―externalities‖—that

is, economic impacts not included in the cost of products. Regarding the

environment, most of these are negative externalities—pollution, destruction of

natural habitats, depletion of shared resources, and other unintended and often

unappreciated damage to ―common‖ resources. This damage is the topic of the

second metaphor, which is rooted in Aristotle‘s observation that we tend to be

thoughtless about things we do not own individually and which seem to be in

unlimited supply. William Foster Lloyd was also an astute observer of this

phenomenon.

In 1833 he described what the ecologist Garrett

Hardin would later call ―the tragedy of the commons. Lloyd observed that cattle

in the common pasture of a village were more stunted than those kept on private

land. The common fields were themselves more worn than private pastures. His

explanation began with the premise that individual farmers are understandably

motivated by self-interest to enlarge their common-pasture herd by one or two

cows, especially given that each act taken by itself does negligible damage.

Yet, when all the farmers behave this way, in the absence of laws constraining

them, the result is the tragedy of overgrazing that harms everyone.

Related Topics