Chapter: Obstetrics and Gynecology: Dysmenorrhea and Chronic Pelvic Pain

Dysmenorrhea

DYSMENORRHEA

Primary

and secondary dysmenorrhea are a source of recurrent disability for a

significant number of women in their early re-

productive

years. It is uncommon for primary dysmenorrheato occur

during the first three to six menstrual cycles, when regular ovulation is not

yet well-established. The incidence of primary dysmenorrhea is greatest in

women in their late teens to early 20s and declines with age. Secondary

dysmen-orrhea becomes more common as a woman ages, because it accompanies the

rising prevalence of causal factors. Childbearing does not affect the

occurrence of either pri-mary or secondary dysmenorrhea.

Etiology

Primary dysmenorrhea is caused by

excess prostaglandinF2produced

in the endometrium. Prostaglandin produc-tion in the uterus normally increases

under the influence of progesterone, reaching a peak at, or soon after, the

start of menstruation. With the onset of menstruation, formed prostaglandins

are released from the shedding endome-trium. Prostaglandins are potent

smooth-muscle stimu-lants that cause intense uterine contractions, resulting in

intrauterine pressures that can exceed 400 mm Hg and baseline intrauterine

pressures in excess of 80 mm Hg. Prostaglandin F2α also causes contractions in

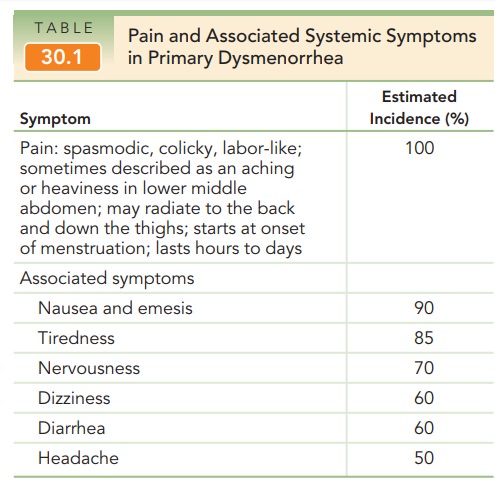

smooth mus-cle elsewhere in the body, resulting in nausea, vomiting, and

diarrhea (Table 30.1). In addition to the increase in prostaglandins from

endometrial shedding, necrosis of endometrial cells provides increased substrate

arachi-donic acid from cell walls for prostaglandin synthesis. Besides

prostaglandin F2α,

prostaglandin E2 is also pro-duced in the uterus. Prostaglandin E2,

a potent vasodilator and inhibitor of platelet aggregation, has been implicated

as a cause of primary menorrhagia.

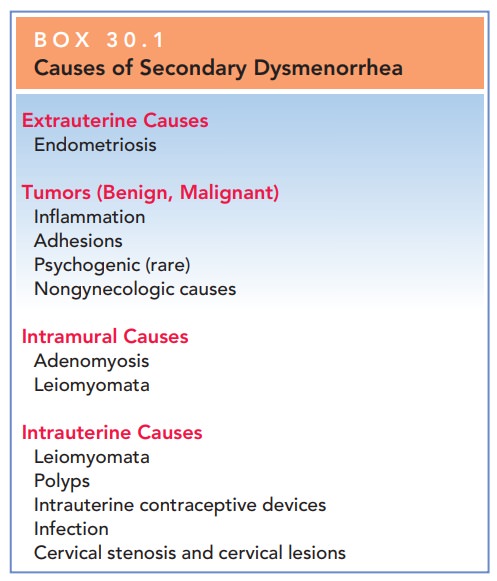

Secondary dysmenorrhea is caused

by structural ab-normalities or disease processes that occur outside the

uterus, within the uterine wall, or within the uterine cavity (Box 30.1).

Common causes of secondary dysmen-orrhea include endometriosis (the presence of ectopic endometrial tissue outside

of the uterus), adenomyosis (the

presence of ectopic endometrial tissue within the myometrium), adhesions, pelvic inflammatory disease, and leiomyomata (uterine fibroids).

Box 30.1

Causes of Secondary Dysmenorrhea

Extrauterine Causes

Endometriosis

Tumors (Benign, Malignant)

Inflammation

Adhesions

Psychogenic (rare)

Nongynecologic causes

Intramural Causes

Adenomyosis

Leiomyomata

Intrauterine Causes

Leiomyomata

Polyps

Intrauterine contraceptive devices

Infection

Cervical stenosis and cervical lesions

SYMPTOMS

In patients with primary

dysmenorrhea, the pain is often diffusely located in the lower abdomen and

suprapubic area, with radiation around or through to the back. The pain is

described as “coming and going” or similar to labor. The patient often

illustrates her description with a fist opening and closing. This pain is

frequently accompanied by moderate to severe nausea, vomiting, and/or diarrhea.

Fatigue, low backache, and headache are also common. Patients often assume a

fetal position in an effort to gain re-lief, and many report having used a

heating pad or hot water bottle in an effort to decrease their discomfort.

In patients with secondary

dysmenorrhea, the pain often lasts longer than the menstrual period. It may

start before menstrual bleeding begins, become worse dur-ing menstruation, then

persist after menstruation ends. Secondary dysmenorrhea often starts later in

life than primary dysmenorrhea.

HISTORY

The specific complaints that an

individual patient has are determined by the underlying abnormality. Therefore,

a careful medical history often suggests the underlying prob-lem and helps

direct further evaluations. Complaints of heavy menstrual flow, combined with

pain, suggest uterine changes such as adenomyosis, leiomyomata, or polyps.

Pelvic heaviness or a change in abdominal contour should raise the possibility

of large leiomyomata or intraabdomi-nal neoplasia. Fever, chills, and malaise

suggest infection. A coexisting complaint of infertility may suggest

endo-metriosis or chronic pelvic inflammatory disease.

ASSESSMENT

For

patients with dysmenorrhea, the physical examination is directed toward

uncovering possible causes of secondary dysmen-orrhea. A pelvic

examination may reveal asymmetry orirregular enlargement of the uterus,

suggesting leiomy-omata or other tumors. Uterine leiomyomata are easily

rec-ognizable on bimanual exam by their smooth contour and rubbery solid

consistency. Adenomyosis may cause a ten-der, symmetrically enlarged, “boggy”

uterus. This diagno-sis is supported by exclusion of other causes of secondary

dysmenorrhea, but definitive diagnosis can be made only by histologic

examination of a hysterectomy specimen. Painful nodules in the posterior

cul-de-sac and restricted motion of the uterus should suggest endometriosis.

Restricted motion of the uterus is also found in cases of pelvic scarring from

adhesions or inflam-mation. Thickening and tenderness of the adnexal

struc-tures caused by inflammation may suggest this diagnosis as the cause of

secondary dysmenorrhea. Cultures of the cervix for Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia

trachoma-tis should be obtained if infection is suspected. In some

patients, a final diagnosis may not be established without invasive procedures,

such as laparoscopy.

In evaluating the patient thought

to have primary dysmenorrhea, the most important differential diagnosis is that

of secondary dysmenorrhea. Although the patient’s history is often

characteristic, primary dysmenorrhea should not be diagnosed without a thorough

evaluation to eliminate other possible causes.

Physical

finding of patients with primary dysmenorrhea should be normal.

There should be no palpable abnormalities of the uterus or adnexa, and no abnormalities should be found on speculum or abdominal examinations. Patients exam-ined while experiencing symptoms often appear pale and “shocky,” but the abdomen is soft and nontender, and the uterus is normal.

Therapy

Primary

dysmenorrhea is an appropriate diagnosis for patients with dysmenorrhea in whom

no other clinically identifiable cause is apparent. Patients

with primary dysmenorrhea generallyexperience exceptional pain relief through

the use of non-steroidal

anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), which areprostaglandin-synthetase

inhibitors. Ibuprofen, naproxen, and mefenamic acid are commonly prescribed

NSAIDs for primary dysmenorrhea. For a time, cyclo-oxygenase inhibitors (COX-2

inhibitors) were becoming the NSAID of choice because of their targeted action.

However, these drugs are now rarely used because of their potential

associ-ation with life-threatening cardiovascular and gastrointesti-nal

effects. Recent studies suggest that continuous low-level topical heat therapy

can provide pain relief comparable to that offered by NSAID therapy without the

systemic side effects that may occur with these drugs.

Therapy with nonsteroidal

anti-inflammatory agents is generally so successful that, if some response is

not evident, the diagnosis of primary dysmenorrhea should be reevaluated. Other

useful components of therapy for pri-mary dysmenorrhea include the application

of heat; exercise; psychotherapy and reassurance; and, on occasion, endocrine

therapy, i.e., oral contraceptives to induce anovulation.

In the rare patient who does not

respond to medical and other therapy and whose pain is so severe as to be

incapacitating, presacral neurectomy

may be a consider-ation. The procedure involves surgical disruption of the

“presacral nerves,” the superior hypogastric plexus, which is found in the

retroperitoneal tissue from the fourth lum-bar vertebra to the hollow over the

sacrum. The risk of intraoperative complications, including injury to adjacent

vascular structures and long-term sequelae such as chronic constipation, limit

the use of this surgical procedure.

For secondary dysmenorrhea, when

a specific diagnosis is possible, therapy directed at the underlying condition

is most likely to succeed. When definitive therapy cannot be used—for example,

in the case of a patient with adenomyosis who wishes to preserve

fertility—symptomatic therapy in the form of analgesics or modification of the

menstrual cycle may be effective.

Combined

oral contraceptives can be useful inpatients who do

not desire childbearing and who do not have contraindications to their use.

They work by suppress-ing ovulation and stabilizing estrogen and progesterone

lev-els, with a resultant decrease in endometrial prostaglandins and

spontaneous uterine activity. Oral contraceptives may be taken in the

traditional 28-day cycle, or in an extended fashion that increases the interval

between menses.

Related Topics