Chapter: Obstetrics and Gynecology: Dysmenorrhea and Chronic Pelvic Pain

Chronic Pelvic Pain

CHRONIC PELVIC PAIN

Chronic pelvic pain is a common

disorder that repre-sents significant disability and utilization of resources.

Estimates suggest that 15% to 20% of women aged 18 to 50 years have chronic

pelvic pain that lasts longer than 1 year. Although there is no generally

accepted definition of chronic pelvic pain, one

proposed definition is noncyclic painlasting for more than 6 months that

localizes to the anatomic pelvis, anterior abdominal wall at or below the

umbilicus, the lumbosacral back, or the buttocks and is of sufficient severity

to cause functional disability or lead to medical care. Chronicpelvic pain

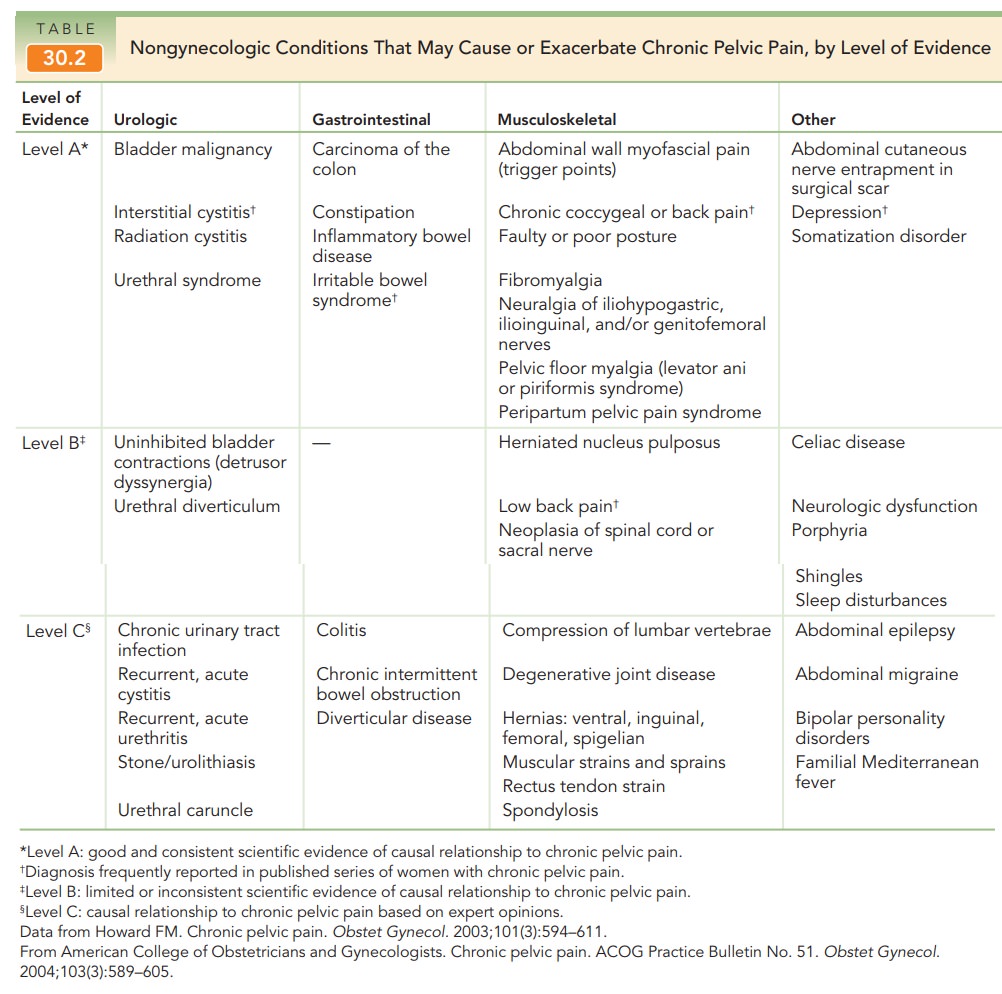

may be caused by diseases of the reproduc-tive, genitourinary, and

gastrointestinal tracts (Box 30.2 and Table 30.2). Other potential somatic

sources of pain include the pelvic bones, ligaments, muscles, and fascia.

Sometimes there is no clear etiology for the pain.

Assessment

The successful evaluation and

treatment of chronic pelvic pain requires time and a patient, caring physician.

The taking of the history and physical examination is a time in which the

physician may both gather information and establish a trusting rapport.

Effective management of this disease is dependent on a good doctor–patient

relation-ship, and the therapeutic effects of the relationship itself should

not be overlooked.

As with the evaluation of any

pain, attention must be paid to the description and timing of the symptoms

in-volved. The history should include a thorough medical, surgical, menstrual,

and sexual history. Inquiries should be made into the patient’s home and work

status, social his-tory, and family history (past and present). The patient

should be questioned about sleep disturbances and other signs of depression, as

well as a past history of physical and

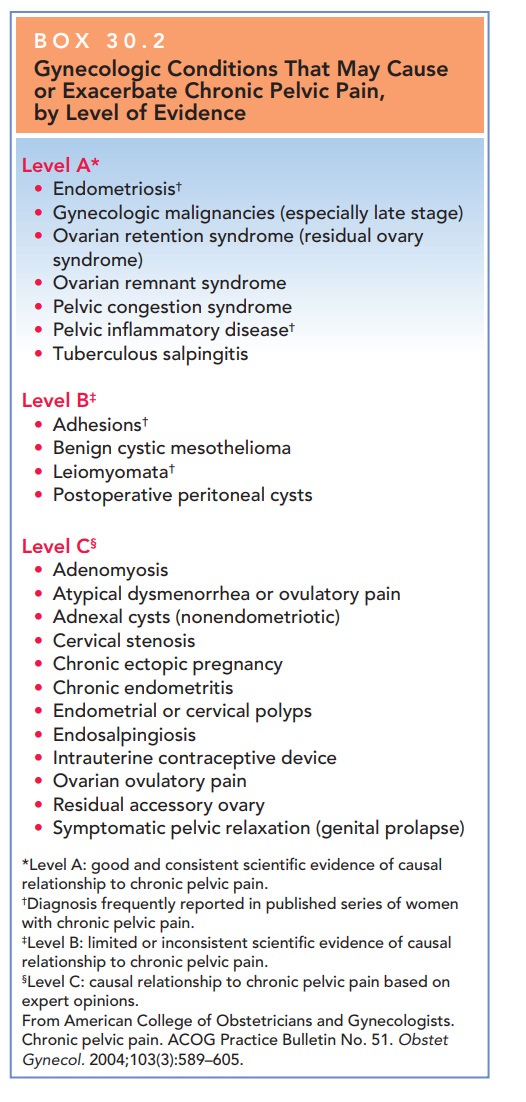

Box 30.2

Gynecologic Conditions That May Cause or Exacerbate Chronic Pelvic Pain, by Level of Evidence

Level A*

·

Endometriosis†

·

Gynecologic

malignancies (especially late stage)

·

Ovarian

retention syndrome (residual ovary syndrome)

·

Ovarian

remnant syndrome

·

Pelvic

congestion syndrome

·

Pelvic

inflammatory disease†

·

Tuberculous

salpingitis

Level B‡

·

Adhesions†

·

Benign

cystic mesothelioma

·

Leiomyomata†

·

Postoperative

peritoneal cysts

Level C§

·

Adenomyosis

·

Atypical

dysmenorrhea or ovulatory pain

·

Adnexal

cysts (nonendometriotic)

·

Cervical

stenosis

·

Chronic

ectopic pregnancy

·

Chronic

endometritis

·

Endometrial

or cervical polyps

·

Endosalpingiosis

·

Intrauterine

contraceptive device

·

Ovarian

ovulatory pain

·

Residual

accessory ovary

·

Symptomatic

pelvic relaxation (genital prolapse)

*Level

A: good and consistent scientific evidence of causal relationship to chronic

pelvic pain.

†Diagnosis frequently reported in published series of women with chronic pelvic pain.

‡Level B: limited or inconsistent scientific evidence of causal relationship to chronic pelvic pain.

§Level C: causal relationship to chronic pelvic pain based on expert opinions.

From

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Chronic pelvic pain. ACOG

Practice Bulletin No. 51. ObstetGynecol. 2004;103(3):589–605.

Studies have found

a significant correlation between a history of abuse and chronic pain. If a

history of abuse is obtained, the patient should also be screened for any

current physical or sexual abuse.

Physical examination of patients

with chronic pain is directed toward uncovering possible causative pathologies.

The patient should be asked to indicate the location of the pain as a guide to

further evaluation and to provide some indication of the character of the pain.

If the pain is local-ized, the patient will point to a specific location with a

single finger; if the pain is diffuse, the patient will use a sweeping motion

of the whole hand. Maneuvers that du-plicate the patient’s complaint should be

noted, but undue discomfort should be avoided to minimize guarding, which would

limit a thorough examination.

Many of

the same conditions that cause secondary dys-menorrhea may cause chronic pain

states. As in the evaluationof patients with dysmenorrhea,

cervical cultures should be obtained if infection is suspected. For most

patients, a reasonably accurate differential diagnosis can be established

through the history and physical examination. The wide range of differential

diagnoses possible in chronic pelvic pain lends itself to a multidisciplinary

approach, which might include psychiatric evaluation or testing. Consultation

with social workers, physical therapists, gastroenterologists,

anesthesiologists, orthopaedists, and others should be con-sidered. The use of

imaging technologies or laparoscopy may also be required to determine a

diagnosis. However, in approximately one-third of patients with chronic pelvic

pain who undergo laparoscopic evaluation, no identifi-able cause is found.

However, two-thirds of these patients have potential causes identified where

none was apparent before laparoscopy.

The evaluation should begin with

the presumption that there is an organic cause for the pain. Even in patients

with obvious psychosocial stress, organic pathology can and does occur. Only

when other reasonable causes have been ruled out should psychiatric diagnoses

such as som-atization, depression, or sleep and personality disorders be

entertained.

Conditions That Increase the Risk of Chronic Pelvic Pain

Common disorders in women with

chronic pelvic pain are pelvic inflammatory disease, irritable bowel syndrome,

interstitial cystitis, endometriosis, and adhesions. However, it is sometimes

difficult to pinpoint a specific cause of chronic pelvic pain, and many women

with chronic pelvic pain have more than 1 disease that might lead to pain.

Pelvic Inflammatory Disease

Approximately

18% to 35% of women who have had pelvic inflammatory disease will develop

chronic pelvic pain. Theexact mechanism is unknown,

but may involve chronic inflammation, adhesive disease, and the coexistence of

psychosocial factors.

IRRITABLE BOWEL SYNDROME

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) occurs in 50% to 80%of women with chronic pelvic pain.

The diagnosis of IBS is defined by the Rome II criteria: abdominopelvic pain

for 12 weeks (not necessarily consecutive) in the preced-ing 12 months that

cannot be explained by known disease, having at least two of the following

features: (1) relieved with defecation, (2) onset associated with a change in

the frequency of bowel movements (diarrhea or constipation), or (3) onset

associated with a change in the form of stool (loose, watery, with mucus, or pellet-like).

IBS is often usefully subcategorized for purposes of treatment depend-ing on

the predominant complaint: pain, diarrhea, con-stipation, or alternating

constipation and diarrhea. The pathophysiology of the syndrome is not clearly

identi-fied, but factors proposed to be involved include altered bowel

motility, visceral hypersensitivity, psychosocial factors (especially stress),

an imbalance of neurotransmit-ters (especially serotonin), and infection (often

indolent or subclinical). A history of childhood sexual or physical abuse is

highly correlated with the severity of symptoms experienced by those with IBS.

INTERSTITIAL CYSTITIS

Interstitial

cystitis is a chronic inflammatory condition ofthe bladder

that is often characterized by pelvic pain, uri-nary urgency and frequency, and

dyspareunia. The pro-posed etiology is a disruption of the glycosaminoglycan layer that normally coats the mucosa of the

bladder. The interstitial cystitis symptom index predicts the diagnosis of

interstitial cystitis and may be used to help determine whether cystoscopy is

indicated. Further evaluation can be done with bladder distention with water or

intravesical potassium sensitivity testing.

Related Topics