Chapter: Modern Pharmacology with Clinical Applications: Drugs Used in Gastrointestinal Disorders

Drugs that Decrease or Neutralize Gastric Acid Secretion

DRUGS THAT

DECREASE OR NEUTRALIZE GASTRIC ACID SECRETION

Functionally, the gastric

mucosa is divided into three ar-eas of secretion. The cardiac gland area secretes mucus and pepsinogen. The oxyntic (parietal) gland area, which

corresponds to the fundus and body of the stomach, se-cretes hydrogen ions,

pepsinogen, and bicarbonate. The pyloric

gland area in the antrum secretes gastrin and mucus.

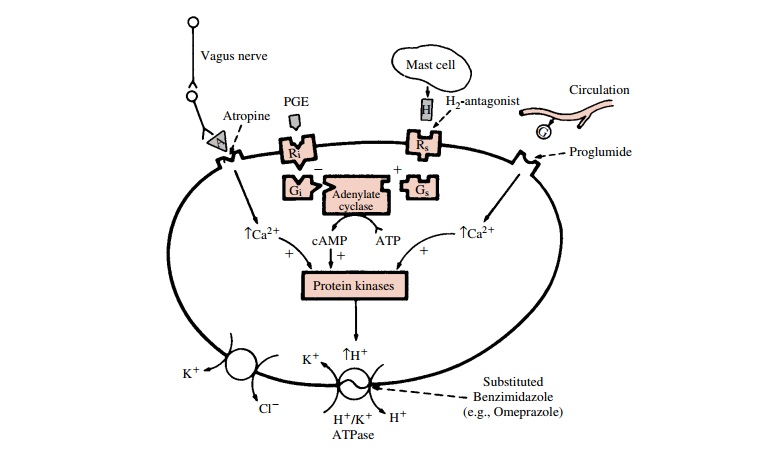

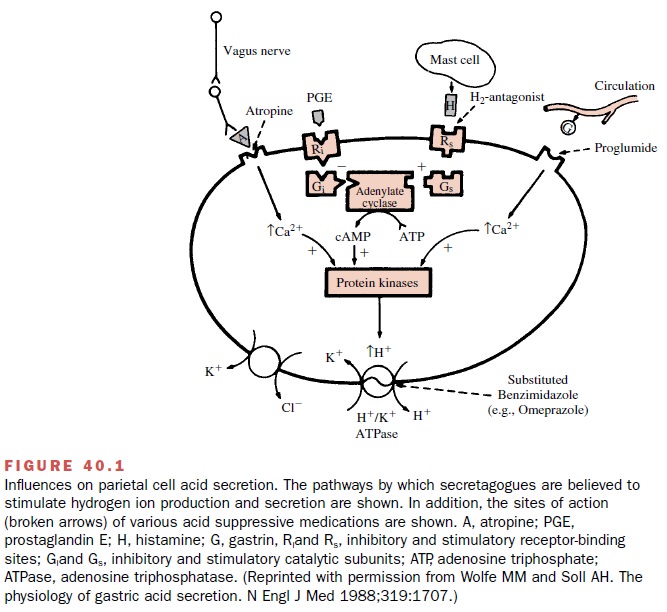

The parietal cells secrete H+

in response to gastrin, cholinergic, and histamine stimulation (Fig. 40.1).

Both cholinergic- and gastrin-induced types of stimulation bring about a

receptor-mediated rise in intracellular cal-cium, an activation of

intracellular protein kinases, and eventually an increased activity of the H+

–K+ pump leading to acid secretion into the gastric lumen.

Follow-ing histamine stimulation, a guanine nucleotide–binding protein (Gs)

activates adenylyl cyclase, leading to an in-crease in intracellular levels of

the second messenger, cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP). Activation of

cAMP-dependent protein kinases initiates the stimu-lation of the H+ –K+

pump.

The cephalic–vagal axis, gastric distention, and local mucosal chemical receptors can modulate acid secre-tion by the stomach. The smell, taste, sight, or discussion of food may result in cephalic–vagal postganglionic cholinergic stimulation of target parietal cells and en-hanced antral gastrin release. After food is ingested, gastric distention initiates vagal stimulation and short intragastric neural reflexes, both of which increase acid secretion. Proteins in ingested meals also stimulate acid secretion. Evidence from animal studies suggests that after protein amino acids are converted to amines, gas-trin is released.

Gastric acid secretion is

inhibited in the presence of acid itself. A negative feedback occurs when the

pH ap-proaches 2.5 such that further secretion of gastrin is in-hibited until

the pH rises. Ingested carbohydrates and fat also inhibit acid secretion after

they reach the intes-tines; several hormonal mediators for this effect have

been proposed. The secretion of pepsinogen appears to parallel the secretion of

H+ , while the patterns of secre-tion of mucus and bicarbonate have

not been well char-acterized.

The integrity of the mucosal

lining of the stomach and proximal small bowel is in large part determined by

the mucosal cytoprotection provided by mucus and bi-carbonate secretion from

the gastric and small bowel mucosa. Mucus retards diffusion of the H+

from the gas-tric lumen back into the gastric mucosal surface. In ad-dition,

the bicarbonate that is secreted into the layer be-tween the mucus and

epithelium permits a relatively high pH to be maintained in the region next to

the mu-cosal surface. If any H+ does diffuse back to the level of

the mucosal surface, both the

local blood supply and the ability of the local cells to buffer this ion will

ultimately determine whether peptic ulceration will occur. With duodenal and

gastric peptic ulcer disease, a major causative cofactor is the presence of

gastric Helico-bacter pylori infection.

Medications that raise

intragastric pH are used to treat peptic ulcer disease and gastroesophageal

reflux disease. In addition, agents that enhance mucosal cyto-protection are

used to decrease ulcer risk.

Antacids

The rationale for the use of

antacids in peptic ulcer dis-ease lies in the assumption that buffering of H+

in the stomach permits healing. The use of both low and high doses of antacids

is effective in healing peptic ulcers as compared with placebo. Healing rates

are comparable with those observed after the use of histamine (H2)

blocking agents. The buffering agents in the various antacid preparations

consist of combinations of ingredi-ents that include sodium bicarbonate,

calcium carbon-ate, magnesium hydroxide, and aluminum hydroxide. If diarrhea

occurs or if there is renal failure, a magnesium-based preparation should be

discontinued. The agents are generally safe, but some patients resist because

some of the formulations are unpalatable and expensive.

A variety of adverse effects

have been reported fol-lowing the use of antacids. If sodium bicarbonate is

ab-sorbed, it can cause systemic alkalization and sodium overload. Calcium

carbonate may induce hypercalcemia and a rebound increase in gastric secretion

secondary to the elevation in circulating calcium levels. Magnesium hydroxide

may produce osmotic diarrhea, and the ex-cessive absorption of Mg in patients

with renal failure may result in central nervous system toxicity. Aluminum

hydroxide is associated with constipation; serum phos-phate levels also may

become depressed because of phosphate binding within the gut. The use of

antacids in general may interfere with the absorption of a number of

antibiotics and other medications.

H2-Receptor Antagonists

The histamine receptor

antagonists (H2 blockers) mar-keted in the United States are

cimetidine (Tagamet), ranitidine (Zantac), famotidine (Pepcid), and nizatidine (Axid). These agents bind to the H2-receptors

on the cell membranes of parietal cells and prevent histamine-induced

stimulation of gastric acid secretion. After pro-longed use, down-regulation of

receptor production oc-curs, resulting in tolerance to these agents. H2-blockers

are approved for the treatment of gastroesophageal re-flux disease, acute ulcer

healing, and post–ulcer healing maintenance therapy. Although there are

substantial differences in their relative potency, 70 to 85% of duo-denal

ulcers are healed during 4 to 6 weeks of therapy with any of these agents. The

incidence of healing of gastric ulceration after 6 to 8 weeks of therapy

ap-proaches 60 to 80% with the use of cimetidine or raniti-dine. Since

nocturnal suppression of acid secretion is particularly important in healing,

nighttime-only dosing can be used. Most are available in low-dose

over-the-counter formulations.

Cimetidine, the first

released H2-blocker, like hista-mine, contains an imidazole ring

structure. It is well ab-sorbed following oral administration, with peak blood

levels 45 to 90 minutes after drug ingestion. Blood lev-els remain within

therapeutic concentrations for ap-proximately 4 hours after a 300-mg dose.

Following oral administration, 50 to 75% of the parent compound is excreted

unchanged in the urine; the rest appears pri-marily as the sulfoxide

metabolite.

Cimetidine may infrequently

cause diarrhea, nau-sea, vomiting, or mental confusion. A rare association with

granulocytopenia, thrombocytopenia, and pancy-topenia has been reported.

Gynecomastia has been demonstrated in patients receiving either high-dose or long-term

therapy. This occurs because cimetidine has a weak antiestrogen effect. Since

cimetidine is partly me-tabolized by the cytochrome P450 system,

coadminis-tered drugs such as the benzodiazepines, theophylline, and warfarin,

which are also metabolized by this system, may accumulate if their dosage is

not adjusted.

Ranitidine is well absorbed

after oral administra-tion, with a peak plasma level achieved 1 to 3 hours

af-ter ingestion. Elimination is by renal (25%) and hepatic (50%) routes. The

half-life of elimination is 2.5 to 3.0 hours. Nizatidine is the newest H2-receptor

antagonist. Similar to ranitidine, it has a relative potency twice that of

cimetidine. About 90% of an oral dose is absorbed, with a peak plasma

concentration occurring after 0.5 to 3 hours; inhibition of gastric secretion

is present for up to 10 hours. The elimination half-life is 1 to 2 hours, and

more than 90% of an oral dose is excreted in the urine. Famotidine has an onset

of effect within 1 hour after oral administration, and inhibition of gastric

secretion is present for the next 10 to 12 hours. It is the most potent H2-blocker.

Elimination is by renal (65–70%) and he-patic (30–35%) routes. Ranitidine,

famotidine, and niza-tidine do not alter the microsomal cytochrome P450

metabolism of other drugs, nor do they cause gyneco-mastia. A reduction in

dosage of any of the H2-blockers is recommended in the presence of

renal insufficiency.

Proton Pump Inhibitors

The proton pump inhibitors

available in the United States are omeprazole (Prilosec), lansoprazole (Prevacid),

pan-toprazole (Protonix), rabeprazole

(Aciphex), and es-omeprazole (Nexium). These are substituted

benzimida-zole prodrugs, which accumulate on the luminal side of parietal

cells’ secretory canaliculi. They become acti-vated by acid transport and then

bind covalently to the actual H+ –K ATPase enzymes (proton pumps)

irreversibly blocking them. These drugs

markedly inhibit gastric acid

secretion. New proton pumps are continu-ously formed, and thus no tolerance

develops. Peptic ulcers and erosive esophagitis that are resistant to other

therapies will frequently heal when these agents are used. The proton pump

inhibitors are also used to treat patients with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, which is the result of a

gastrin-hypersecreting neuroendocrine tumor.

The prodrugs are unstable in

the presence of acid and therefore must be administered as an enteric-coated

preparation or as a buffered suspension. Pantoprazole is also available in an

intravenous formulation. The most commonly reported side effects are diarrhea

and headache. Hypergastrinemia has been noted as a reac-tion to the marked

reduction in acid secretion. Gastric carcinoid tumors have developed in rats

but not in mice or in human volunteers, even after long-term use.

Related Topics