Chapter: Modern Pharmacology with Clinical Applications: Drug Metabolism and Disposition in Pediatric and Gerontological Stages of Life

Drug Disposition in Geriatric Patients

DRUG DISPOSITION

IN GERIATRIC PATIENTS

The elderly (individuals over

65 years of age) constitute more than 13% of the population. This figure is

increas-ing steadily and is expected to reach 50 million by the year 2020. This

segment of our society is the most highly drug-treated and accounts for about

25% of prescrip-tion drugs dispensed. The average Medicare patient in an

acute-care hospital receives approximately 10 differ-ent drugs daily, and this

translates into a higher inci-dence of adverse drug reactions in geriatric

patients than in the general population.

Chronological aging may not

necessarily be an accu-rate index of biological aging, which is the result of

many genetic and environmental factors. While most 20-year-olds have a similar

response to a given drug, it is difficult to predict the response among

80-year-olds. A clear relationship between the appearance of untoward effects

to drugs and aging has been demonstrated only for about 10 drugs. For some 90

other drugs in common clinical use, age alone was not a major determinant of

clinical toxicity. It is apparent that an increase in life span is accompanied

by an increase in chronic illnesses such as hypertension, congestive heart

failure, arthritis, and diabetes. The pharmacological management of these

conditions, especially when the same person has several diseases, becomes

increasingly complex.

Age-related alterations in

pharmacokinetics (ab-sorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion) have

received considerable attention. Thus, physiological changes in elderly

patients, when taken together, may contribute to impairments in drug clearance

in this seg-ment of the population (Table 6.5).

Absorption

Elderly patients may absorb

drugs less completely or more slowly because of decreased splanchnic blood flow

or delayed gastric emptying. Reduced gastric acidity may decrease the

absorption of drugs that require high acidity.

Distribution

Drug distribution in elderly patients may be altered by hypoalbuminemia, qualitative changes in drug-binding sites, reductions in relative muscle mass, increases in the proportion of body fat, and decreases in total body water. The plasma level of free, active drug is often a di-rect function of the extent of drug binding to plasma proteins. There is a well-documented age-dependent decline (about 20%) in plasma albumin concentration in humans due to a reduced rate of hepatic albumin synthesis.

These changes in

serum albumin may affect the free drug concentration for a number of highly

bound drugs, such as phenytoin, warfarin, and meperidine.

Metabolism

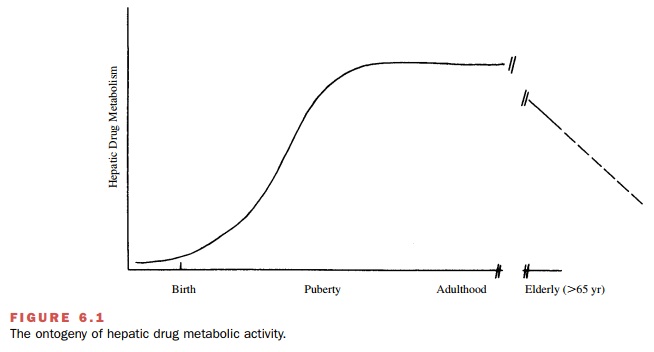

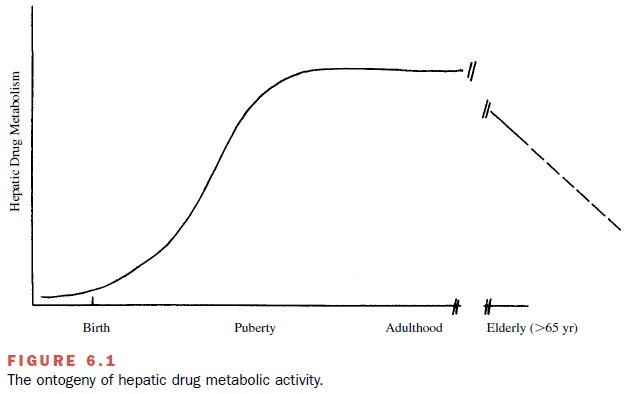

In addition to changes in

metabolism that occur as a re-sult of reduced hepatic enzyme activity,

metabolism may be impaired by a reduction in hepatic mass, vol- ume, and blood

flow (Fig. 6.1). Phase I oxidative path-ways are decreased with age, while

phase II conjugation pathways are unchanged.

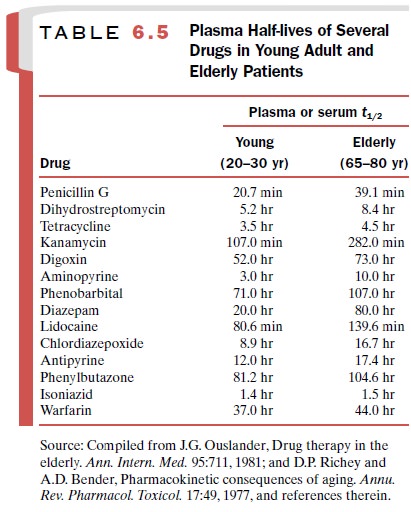

In a carefully controlled

clinical study, the plasma half-life of diazepam (Valium), a widely used

antianx-iety agent, exhibited a striking age dependency. In pa-tients aged 20

years, the t1/2was about 20 hours, and this increased linearly with

age to about 90 hours at 80 years. Half-lives of other drugs in young and old

pa-tients are presented in Table 6.5. These data demon-strate changes in drug

half-life with increasing age, suggesting that at least for some drugs, elderly

patients have reduced metabolism, drug clearance, or both.

Excretion

Renal elimination of foreign

compounds may change dramatically with increasing age by factors such as

re-duced renal blood flow, reduced glomerular filtration rate, reduced tubular

secretory activity, and a reduction in the number of functional nephrons. It

has been esti-mated that in humans, beginning at age 20 years, renal function declines

by about 10% for each decade of life. This decline in renal excretion is

particularly important for drugs such as penicillin and digoxin, which are

elim-inated primarily by the kidney.

Adverse Drug Effects

The incidence of iatrogenic complications is three to five times greater in the elderly than in the general pop-ulation. Adverse drug reactions account for 20 to 40% of these complications. Inappropriate drug use has been noted in almost half of hospitalized elderly patients. One-fourth of these patients were receiving contraindi-cated drugs, and three-fourths were receiving unnecessary drugs. Half of adverse drug reactions occur in pa-tients receiving inappropriate drugs.

Delirium and cognitive

impairment are common ad-verse reactions in the elderly. While almost every

class of drugs has the potential to produce delirium in the elderly, it is most

frequent with psychoactive drugs. The risk increases with the number of drugs

the patient is re-ceiving, reaching a 14-fold increase in risk for patients

taking more than 6 drugs.

Special Considerations

The following should be

considered when prescribing drugs for elderly patients.

Drugs should be prescribed

only if nonpharmaco-logical techniques are ineffective, such as for problems

like sleeplessness and anxiety. When drugs are pre-scribed for these

conditions, they should be given for a limited time and the patient closely

monitored for ad-verse effects. Dosage should start at or below the lowest

recommended levels.

Keep it simple. Prescribe

drugs only if you have available extensive experience and prescribing

informa-tion for that drug in elderly patients. Use the least num-ber of drugs

and doses per day Reevaluate the continued use of all medications the patient

is receiving, including over-the-counter medica-tions, on a regular basis.

Noncompliance is a

significant problem, with almost 50% of elderly patients failing to take their

medications as prescribed. Some of the reasons for noncompliance are inability

to pay for the drug, side effects, mental impair-ment, and inability to

understand complex instructions.

Related Topics